The story of the mysterious sea serpent of Stronsay

The Stronsay Beast, as it would come to be known, was discovered in the aftermath of a winter storm in 1808.

Stunned local fishermen described seeing something altogether alien in the water and they weren’t the only ones left scratching their heads.

Advertisement

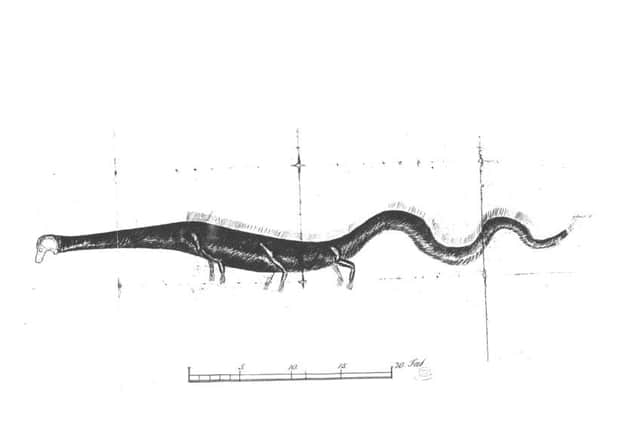

Hide AdEyewitnesses claimed that the beast was of incredible length, with a long slender neck, three pairs of legs, a tail and a hairy mane.

A contemporary description read: “The body measured fifty-five feet in length, and the circumference of the greatest part might be equal to the girth of an Orkney pony. The head was not larger than that of a seal, and was furnished with two blow-holes. From the back a number of filaments (resembling in texture the fishing tackle known by the name of silk-worm gut) hang down like a mane. On each side of the body were three large fins, shaped like paws, and jointed.”

One needs only to read that to note the striking similarity with the Loch Ness Monster.

Unfortunately, by the time the experts arrived on the scene, what remained of the beast had decayed to the point that it was difficult to determine if this was the real deal.

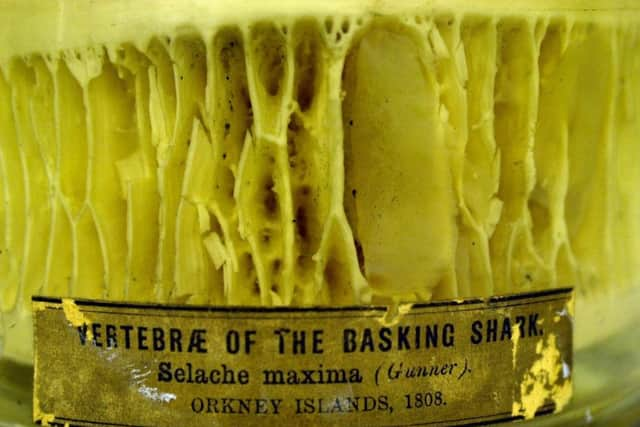

Bits of the carcass, which included vertebrae segments and strands of hair, were transported to Edinburgh - then one of the most important scientific centres in the Western World - where they were poked, prodded and pondered over by members of the Wernerian Society. Nobody could figure out the mystery, but so convinced were the great minds of the time that this was a newly-discovered species, the beast was given its own scientific name: “Halsydrus Pontoppidani”, after a Norwegian bishop who recorded sea monsters in the 1700s. Even Nessie doesn’t boast her own proper moniker.

However, the mystery was short-lived.

Esteemed surgeon Sir Everard Home brought the beast’s skull and neck bones with him to London, bursting the bubble in the process. Upon closer inspection of the vertebrae, Sir Everard concluded it was the scant remains of a humble basking shark.

Advertisement

Hide AdBasking sharks are not uncommon in the North Sea, particularly during the summer months. They are seen in even greater numbers in the North Atlantic and will occasionally venture close to the west coast of Scotland.

Home’s findings were given further credence in the 1980s by Dr Geoff Swinney, an expert on lower vertebrates, fish, amphibians and reptiles, who asserted that it was 100 per cent certain that it was a basking shark.

And, with that analysis, the Stronsay Beast was dead.

A specimen of the ‘sea serpent’s’ vertebrae is kept by the National Museum of Scotland on Chambers Street in Edinburgh.