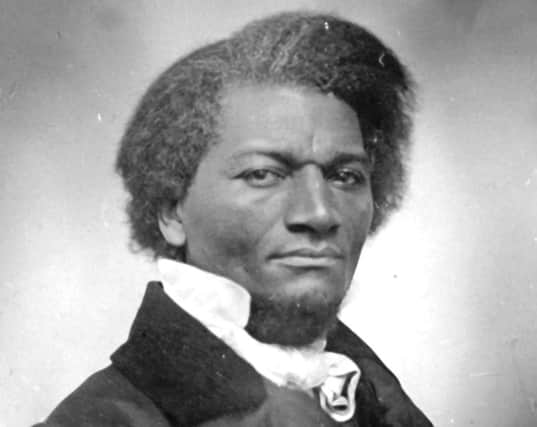

The story of freed slave Frederick Douglass' time in '˜beautiful' Scotland

On 14 April 1876, the eleventh anniversary of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln, an aging but still remarkably robust Frederick Douglass delivered the main speech at the unveiling of the Freedmen’s Memorial Monument in Washington, DC. “He delivered us from bondage,” Douglass said of the great leader the memorial commemorated and whom he had befriended during the American Civil War. The crowd gathered around him included President Ulysses S. Grant, Supreme Court judges, congressmen and diplomats. The former slave was used to such illustrious company; the once-frightened youth whose back had been ripped open by the whip having long-since transformed himself into a writer and orator of world renown.

Scotland had played a role in the remarkable change, with the slave who had been born Frederick Bailey even taking the name he adopted as his own after escaping north at the age of 20 from a swashbuckling character in Sir Walter Scott’s The Lady of the Lake. Douglass also visited in 1846 as part of near-two-year tour of Britain and Ireland, a trip undertaken after the publication of his incendiary autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, made him a target for slave-catchers. He stopped in Glasgow first, receiving a warm welcome amid the bleak January rains from abolitionists like the Quaker grocer William Smeal and the businessman Andrew Paton. The thrusting port city on the River Clyde had been home to a vibrant anti-slavery community for many years even though it was also one of the places to have profited most from the country’s involvement in slavery and the slave trade, a connection with which it has only recently really started coming to terms.

Advertisement

Hide AdDouglass stayed in the Gallowgate area of the city with Smeal, a bespectacled, frock-coated figure in a picture taken in the 1860s, whose nose seems to have been disfigured either from birth or through some accident. He gave a number of speeches at the recently-built City Halls, outlining to crowds of thousands how he wanted to ‘encircle’ America “with a cordon of Anti-Slavery feeling – bounding it by Canada on the north, Mexico on the west, and England, Scotland and Ireland on the east, so that wherever the slaveholder went he might hear nothing but denunciations of slavery, that he might be looked down upon as a man-stealing, cradle-robbing and woman-stripping monster and that he might see reproof and detestation on every hand.”

Playing on the intense religiosity that coursed through Scottish society, he also described how the “slave-mother, for teaching her child the letters which composed the Lord’s prayer, could be hung up by the neck till she was dead,” remarks that brought forth fervent shouts of “Shame.”

From Glasgow, Douglass made his way north-east through wintry countryside to Perth, a large town in the shadow of the Ochil Hills that had become something of a draw for literary-minded tourists since the publication of Scott’s The Fair Maid of Perth, one of the last instalments in the writer’s Waverley series of novels, a number of which, including Rob Roy, contained subtle references to Scotland’s role in the slave trade. Another literary-themed excursion would take Douglass to Ayr and the birthplace of Robert Burns, the great poet whom he had admired ever since purchasing a copy of his Collected Works in a Massachusetts bookstore in the early 1840s, a volume he treasured and later passed on to his eldest son. Douglass met Burns’s sister Isabella Begg there and delighted in looking through some of the poet’s own handwritten notes.

More controversially, Douglass got involved in a campaign to get the recently-established Free Church of Scotland to return the thousands of pounds it had raised in the slaveholding states of the American South, money it needed to build churches and schools and pay ministers. Abolitionists, however, believed all such funds were tainted by the blood of the slaves, the striking, six-foot-tall Douglass spending the best part of five months touring towns and cities like Arbroath, Paisley, Kilmarnock and Fife, bellowing out “Send Back the Money” and denouncing Free Church leaders like the Rev Dr Thomas Chalmers. “Their hands are full of blood,” he declared evocatively, quoting from an excoriating passage from the Bible (Isaiah: 4-20).

“The agitation goes nobly on… The very boys in the street are singing out ‘Send back that money,’” Douglass wrote triumphantly from Dundee, where his first talks were so ‘fearfully crowded’ the remainder had to be ticketed. His powerful new catchcall was daubed on the walls of churches and woven into verse. Send back the Money! send it back!/Tis dark polluted gold; began one poem, ‘Twas wrung from human flesh and bones,/By agonies untold:/There’s not a mite in all the sum/But what is stained with blood;/There’s not a mite in all the sum/But what is cursed of God.

A song titled O For Good Luck To Our Coffers had a verse that went: The worthy Free Priest was pleas’d to allow,/That all the Slaveholders were Christians now;/The Doctor he bless’d them for what they had paid,/And wish’d them success in their Slaveholding trade.

Advertisement

Hide AdIn Edinburgh, it has even been suggested Douglass joined the redoubtable Quakers Jane and Eliza Wigham in scaling the heights of Arthur’s Seat, shovel in hand to carve out the phrase in the grass of the craggy hill overlooking the city – a city he would always call the most beautiful he ever visited.

Although the Free Church never sent back the money, Douglass’s tour was an undoubted success, raising the profile of an anti-slavery movement that had been largely in abeyance since the passage of the Slavery Abolition Act in 1833. On a more personal level, he took deep satisfaction from being able to walk the streets unmolested, including in the company of white women like the Wighams and Andrew Paton’s sister Catherine, actions that would have seen him insulted or physically attacked in many towns and cities of even the supposedly ‘free’ northern states. He could enter galleries and museums without care, jump onto omnibuses without a second thought. His choice of train carriages came down to money rather than colour. “I enjoy everything here which may be enjoyed by those of a paler hue – no distinction here,” he informed an abolitionist friend in America. Jim Crow was nowhere to be found.

Advertisement

Hide AdThe tremendous reaction to his talks also gave Douglass, the bicentenary of whose birth was celebrated across the United States earlier this year, the confidence to strike out from the American Anti-Slavery Society (the organisation under whose auspices he had crossed the Atlantic) when he returned to America in 1847, becoming in essence his own movement and the great figure we know today, the vaunted leader of a subjugated people, one whose influence continues to be felt in the words and actions of leading political figures such as the former American president Barack Obama – like Douglass the author of an inspiring autobiography.

Laurence Fenton is a writer and editor living in Cork, Ireland. ‘I Was Transformed’ Frederick Douglass: An American Slave in Victorian Britain, is published by Amberley, £18, www.amberley-books.com; www.laurencefentonbooks.com