The man who mapped the Munros - before Hugh Munro

But it lesser known that a quiet mineralogist from Orkney had long been compiling his own list of peaks on his high-altitude travels which he conducted in tweeds and nailed leather boots while carrying large hammers and heavy bags of rock.

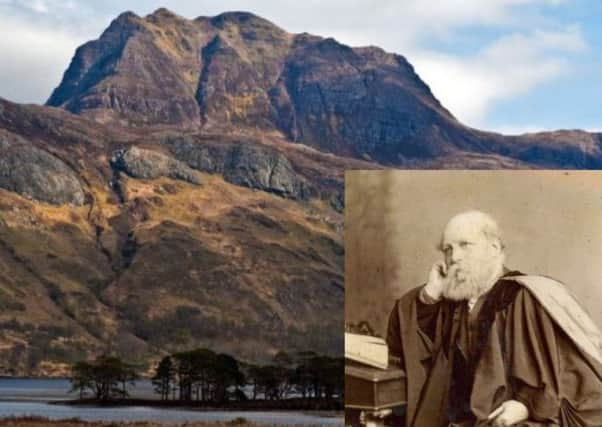

Growing recognition is being given to Professor Matthew Forster Heddle (1828-1897) for his early role in charting the mountains that rise above sea level by 3,000 feet or more.

Advertisement

Hide AdIt is believed that the research of Heddle, who had both a professional and personal passion for the hills, went on to inform the findings of Munro.

Indeed, the two men first met in 1883 and following Heddle’s death, Munro wrote his obituary.

Then, Munro said: “There can be little doubt that Professor Heddle had climbed far more Scottish mountains than any man who has yet lived...No district was unknown to him, and scarcely any high mountain unclimbed by him...”

The life of Heddle has been researched by author Hamish Johnston, the great-great grandson of the scientist, who has written a biography of the mineralogist and mountaineer.

He found a reference to Heddle’s list of ‘Scottish 3000ers’ in the minute of a meeting of St Andrews Literary and Philosophical Society.

The meeting was in February 1891 - just two months after Munro was asked by the Scottish Mountaineering Club to compile his table of mountains.

Advertisement

Hide AdThe minute of the meeting said: “Dr Heddle gave a paper entitled God’s Glory in the Heavens. He mentioned that there were 409 hills in Scotland above 3,000 feet in the Highlands at which he has been at the top of 350.”

Munro’s Tables of the 3000-Feet Mountains of Scotland was published in September 1891.

Advertisement

Hide AdHeddle identified 409 mountains in contrast to Munro’s 538, which were separated into 283 separate mountains and 255 subsidiary tops.

Mr Johnston added: “Perhaps Heddle was less thorough than Munro, but it is also likely that he disregarded many of Munro’s tops.

“It is also likely that Heddle gave his list to Munro to help him with his work.”

Mr Johnston said Heddle’s exploration priorities were driven by his mineralogical work. Height measurements were calculated using an aneroid barometer to track changes in air pressure. Not all parts of the Highlands and Islands were mapped by Ordnance Survey at this time.

However, the scientist climbed 357 of the mountains he had listed by the time his hill-going career was brought to an end in 1891/1892 by old age, infirmity and some access problems driven by the creation of large private sporting estates.

By then, the Rev A.E. Robertson, who is widely considered Scotland’s first Munroist, had completed but a handful of mountains, Mr Johnston said.

Advertisement

Hide AdHe added: “Because he was active before Munro published his tables, Heddle did not differentiate between separate mountains and subsidiary tops.

“Nevertheless, his impressive record of exploration of Scotland is such that, had he known about the distinction, he would easily have been the first Munroist.”

Advertisement

Hide AdHeddle was first a medical doctor in Edinburgh’s Grassmarket then Professor of Chemistry at St Andrews university from 1862 till 1884, but his true vocation was mineralogy.

Heddle’s collection is now held by National Museums Scotland, and his encyclopaedic The Mineralogy of Scotland, published in 1901, is still regarded as the classic work on its subject, Mr Johnston said.

During 60 years of exploration through Scotland’s mainland and islands, he discovered one third of all the mineral species known in Scotland in 1901.

Mr Johnston said: “It is the case that his objective which was to create an encyclopedia of Scottish minerals meant that he had to go absolutely everywhere.

“He had to go everywhere else where others had not been. It was his life’s work but he also loved the hills for their own sake.”

Much of his work involved climbing sea-cliffs and corrie walls, Mr Johnston found.

Advertisement

Hide AdOne of Heddle’s students wrote that, during lectures, Heddle would relate his “...miraculous escapes from death which he more than once had when, suspended by ropes he was collecting minerals from the face of some beetling precipice.”

He once tried to reach minerals he could see in the roof of Fingal’s Cave.

Advertisement

Hide AdMr Johnston is doing a series of talks on his great-great grandfather to illuminate his role in early mountaineering in Scotland.

He added: “Everybody is interested in Scottish topography and hillwalking but nobody has heard of Heddle. He is hardly mentioned at all.

“People are fascinated to learn that here was someone who had done so much before Munro.

“I would like him to have a far more prominent place in the history of mountaineering. It is my aim to get him better known.”

-Matthew Forster Heddle, Mineralogist and Mountaineer, by Hamish H. Johnston, is available now.