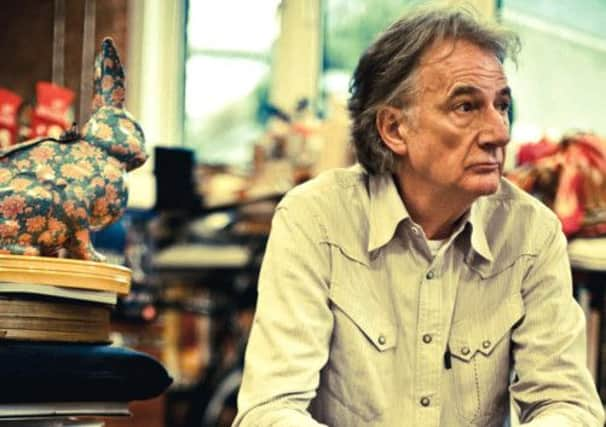

Sir Paul Smith on becoming a designer by accident

This article contains affiliate links. We may earn a small commission on items purchased through this article, but that does not affect our editorial judgement.

PEOPLE send stuff to Sir Paul Smith all the time. Random stuff. He really has no idea why, or how it all started. It just happens. The designer’s office is so crammed he can no longer see his desk, let alone use it.

To my left, he points out an unremarkable bag marked “From PS to PS”. What makes it remarkable is the sender: Patti Smith. Behind it, there is a khaki military jacket from Usain Bolt. Across the boardroom table stands a bike from Mark Cavendish (on which he cycled to victory in the UCI Road World Championships in 2011, and which he rebuilt on the pavement outside the designer’s Covent Garden office, much to the consternation of the reception staff, who were watching on CCTV). There are piles and piles of cycling jerseys, a small collection of Mr Potato Heads, books and books and books, framed photographs, tin signs, creepy looking dolls…

Advertisement

Hide AdEvery morning Smith arrives to more gifts – some anonymous (like a teeny tiny, fully operational train set – sent, it says simply, “From Val”); others are from old friends. A full shelf is given over to the gifts from Margo, a 17-year-old Belgian schoolgirl who has been writing to Smith since she was 11. A favourite is her nativity set made entirely from peanuts. Baby Jesus has lost an eye.

Smith doesn’t use the internet. He doesn’t have an email address. As master of a £200m global empire, you could argue he has minions to do all that stuff for him. But what he does do is get up at around 5am every morning, and go for a swim at the Royal Automobile Club, Pall Mall, arriving fresh-faced in the office at 6am. He then sets about answering each and every correspondent. By hand. Sometimes he also sorts out the plumbing.

“My dad was completely self-contained,” he says. “He never employed a car mechanic or a painter or a plumber, he did everything himself.

“I mended the sink this morning,” he adds proudly, “which made the cleaner really laugh. I was doing the U-bend thing. I’ve never heard her speak any English at all, and then she said, ‘Mr Armani no do this.’”

Some mornings he writes up to 20 postcards of thanks before the rest of the office has even burned their tongues on their first cup of Starbucks. “Every day there’s these delightful cards, letters, gifts, things. People make things. We’ve got origami, wood carvings. The most awesome thing is this bike.” And he guides me to an old-fashioned-looking, but pristine pale green bike. “On my birthday, 5 July, we were sitting having a sandwich and I got a call from reception saying there was a young lady who wanted to give me a present. So I went down and she said, ‘Happy birthday, this is a bicycle I got from the year you were born.’ It was all wrapped up. She said, ‘It was made in Moscow. I’ve just come from there.’ And she flew back in the afternoon.”

He refers to the Kean Street building as “a magical house” – photographs cover the walls (including one of the Dalai Lama wearing a signature Paul Smith striped scarf); the lift is lined with snaps of the staff as children. “This is just the tip of the iceberg. I also have a massive archive in Nottingham and a big room downstairs. I was in my old office from 1982 to 2000, and when I left, it looked like this. This room was empty and I was going to bring everything across but I couldn’t face moving it so I just locked it up. Three weeks ago we unlocked it and the mice and moths had been there a bit, but most of the stuff is fine.”

Advertisement

Hide AdA large batch of that stuff has now taken up residence in London’s Design Museum, in a recreation of the famed office space, as part of an exhibition that takes visitors into the inspirational world of Paul Smith, celebrating the brand and looking behind the famous multi-stripe to what inspires the man who left school at the age of 15 with no qualifications and only one desire – to ride a bike.

“It’s a bit weird,” he says of the honour. “It’s like being knighted. You’re delighted on one hand but on the other you think, ‘Is it really me?’ Then you do it, and it’s lovely.

Advertisement

Hide Ad“The hardest thing is that we needed a space about five times bigger because we could hardly scratch the surface. One of my staff said, ‘Will there be any clothes in it?’ Which I thought was adorable. That’s what we do for a living. And there will be some clothes, but it’s not a retrospective. The exhibition, for me, is about goosebumps. It’s about a young creative, someone who’s starting out, who can go in and walk around and think, ‘Maybe I could do that.’ It’s about giving you an energy or a confidence.”

The first thing visitors will see is a 12-foot-square box. This is the size of Smith’s first shop, ambitiously named Paul Smith Vêtement Pour Homme.

Another room takes us inside Smith’s head – “it’s nicknamed the paracetamol room, because you’ll need one when you get out” – while another has a fake bed and bedside table. “This was the first showroom, which was a hotel bedroom I rented for four days in Paris and nobody came. Eventually, on the last day, at 4pm, one person came and made an order and that was the start.”

The lesson, he says, is be patient, you can do it.

Born in Nottingham on 5 July, 1946, to Irene and Harold Smith, a draper and keen amateur photographer, he can remember nothing before the age of 11 – the momentous year he was given his first bike. “There were no punctuation marks, no arguments, it was just a very gentle house. My sister is eight years older than me, my brother was 11 years older than me, so I was like an only child. I can’t remember school at all – it meant nothing to me.”

Then came the bike and, soon after, the racing. “At the age of 12, I was in the middle of Derbyshire doing 35/40 miles an hour and there was no mum or dad. That was really the start of my life,” he says.

His dream was to be a professional cyclist – though he admits now he was neither strong enough nor brave enough. When he left school at 15, with his father’s words – “Cycling’s not a proper job” – ringing in his ears, he started work in a warehouse in Nottingham selling clothes and shoes instead. But he lived for that bike; didn’t go out to pubs, didn’t have a social life outside the cycling club.

Advertisement

Hide AdHis world caved in when, two years later, he crashed into the back of a car and was hospitalised for three months. He lay in traction at home for months more, then wore calipers. While his cycling friends visited, regaling him with their adventures, he lay there, devastated.

But he’s a sociable sort, is Paul Smith; he can talk to anyone. So when some boys he’d met in hospital said: “Let’s stay in touch,” they did. Their first outing was to a pub that was popular with art students at the time and suddenly a colourful new world of creativity opened up to him. “All I’d known about before then was living at home with my mum and dad and cycling. I was so fascinated by it all – by the pub and rock music and art school – so the transition was less traumatic because my new life was so exciting as well.”

Advertisement

Hide AdIn 1964, he helped a friend set up a clothes shop, doing the window dressing, then graduating to buying. Three years on, he met Pauline Denyer, who was to become his girlfriend and, much later, his wife. He’d never seen anyone like her before. “She looked immaculate. Everything she wore she’d made herself, her hair was cut by Vidal Sassoon when he was just starting out – she just looked different to everyone else.”

Denyer had trained at the Royal College of Art and was teaching a few days a week to fit in with her two young children. She met Smith, they fell in love, she left her husband, and the couple moved in together in Nottingham. “At the age of 21 I got an instant family – two Afghan dogs, two long-haired cats and two kids.”

He gives Denyer the credit for everything. She inspired him to open his first shop – the tiny room on a back alley. She taught him about pattern cutting and construction and never to compromise on quality. “That’s probably one of the reasons I’m still here. At the time there were a lot of good young designers coming out of London, really innovative – far more innovative than I was – but unfortunately their quality wasn’t good.”

The pair finally married in 2001, on the same day Smith was knighted.

“Almost all of this is down to Pauline,” he says. “I mustn’t be disrespectful to my team – they are all fantastic and I couldn’t have done it without them – but Pauline is the foundation of the business. My dad gave me my ability to talk to people, my cycling gave me a competitive spirit, an understanding about team work and progressing, and Pauline – she’s very down to earth, she’s very shy, she shuns any form of celebrity and is very well read. To this day she’s the youngest person ever to get into the Royal College of Art – she was there at 18. She went on to study history of art, then studied painting, she dances Argentine tango…”

She doesn’t have anything to do with fashion these days, but recently visited her husband’s office with a group of local schoolchildren. On seeing his “stuff”, she whispered to one of his staff: “It’s a disease, you’ve got to help him. Please.”

Advertisement

Hide AdSmith has one room in their house that he can fill up; the rest of the space belongs to Mrs Smith, he says. They don’t own a computer; his wife doesn’t even have a mobile phone. “It’s not because we’re luddites,” he insists, “it’s just that she knows how to contact me. Nothing could be that important.”

Forty-four years after opening that first shop, Smith now produces an incredible 28 collections a year, shoots all his own campaign imagery, designs the shops – and has never borrowed a penny, a fact about which he is extremely proud.

Advertisement

Hide Ad“Pauline and I never sat round a table and said, ‘Let’s have a business.’ Then ‘Let’s sell to a different country.’ It’s always just flopped along. That’s probably why it has such continuity,” he reasons, “because a lot of the big popular brands these days have been created by financial institutions that go through the business formula. It’s becoming so clichéd and boring that every street that used to be exciting to visit in Milan or Paris now has all the same shops on it.”

Paul was courted once by what he calls “one of the big ones” – a luxury conglomerate that wanted to buy the business. “Three of my four main guys were tempted, and it cost me a quarter of a million quid just to say no. We let them put in an offer, then my guys said, ‘We know more than they do.’ So they made the decision not to do it, not me.”

He had only gone through the process anyway to prove a point. “First of all you become the slave of the shareholder, which definitely changes the character of the company. And also, you can’t be spontaneous. Good design is very much about spontaneity and following your instincts.”

He adds: “If I was to get £100m today it wouldn’t make any difference to me. I have no desire for a private jet or a boat. I’m very happily in love, I have a lovely house in Italy, a lovely house in London, I adore my job, I’m blessed with having a beautiful day every day.”

Now aged 67, it was about 30 years before Smith got back on a bike again after his crash. The accident, he says, happened for the best. There is a pink, super-light, carbon-fibre bike in his office – one of his own designs – which sold for thousands of pounds and raised money for a cancer charity. On its crossbar there is a tiny red triangle – the flamme rouge – which marks the final kilometre of the Tour de France, the signal to give it all you’ve got. “From bad things, good things can come,” he says.

“The last thing you see when you leave the exhibition is a sentence that says, ‘Every day is a new beginning.’ Yes, you’ve had a difficult time, or your health is not so good, or your husband and you have had a fight but, come on, keep strong, keep positive, find the energy, dig deep. We’re only on the earth for a short amount of time so try to see that the sun looks lovely today.”

Twitter: @Ruth_Lesley

Advertisement

Hide AdHello, My Name Is Paul Smith is at the Design Museum, London, 15 November to 9 March (www.designmuseum.org); tickets cost £11.85 for adults, and £6.50 for U-16, tel: 020 7940 8783, www.ticketweb.co.uk (booking fee applies); www.paulsmith.co.uk