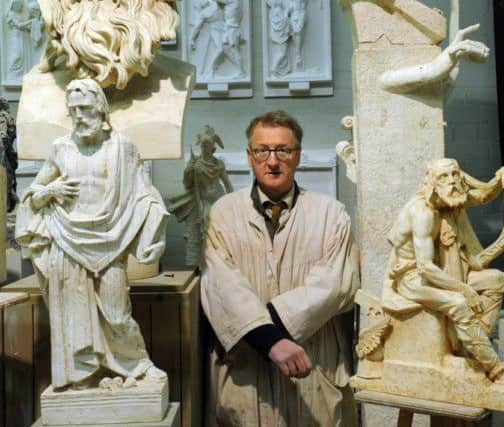

Sculptor Sandy Stoddart on his art

He is mightily attached to this type of footwear, each pair lasting eight years and so punctuating his three-decade career; as they wear out, he places a single boot at the side of the road, enjoying the thought of passers-by scratching their heads at this puzzling sight. It is an amusing idea, and typical of the man – his peculiar mix of pride, humility and whimsy – that he would choose to erect such small, daft, secret monuments to his own life’s work.

Stoddart is 54, the Queen’s Sculptor in Ordinary in Scotland, a title he has held since the end of 2008 and which fits with a general perception of him as establishment to his oxters, the go-to-guy if you should want a great man from Scotland’s past memorialised in bronze. He first came to public attention at the end of the 1980s when his statues of Mercury and other mythological figures were erected as part of Glasgow’s Italian Centre. Real prominence arrived in 1996 with his David Hume on the Royal Mile, and since then he has contributed statues of the economist Adam Smith and physicist James Clerk Maxwell to Edinburgh as well as much work elsewhere. An aluminium sculpture of the muse Clio, daughter of Zeus, was lately lifted into place above the entrance to the Scottish National Portrait Gallery, and he is working at present on a monument to the 19th century architect, William Henry Playfair, for outside the National Museum of Scotland.

Advertisement

Hide AdArguably, though, and no doubt to his dismay, Stoddart is better known for his quick tongue than his deft hands. An outspoken opponent of contemporary art (Tracey Emin is “the high priestess of societal decline, he has said) he is a defender of the classical tradition and a particular set of characteristics and values – intellectualism, hard work, respect, introspection, formality, fastidiousness – which can make him appear stiff and prim. In fact, he is good fun, albeit deeply serious about his work. But he finds, of course, no humour in the Glaswegian tradition of putting a traffic cone on the head of the statue of the Duke of Wellington and has written, sickened, to the papers.

His studio occupies two large rooms on the University of the West of Scotland campus in Paisley. Casts, moulds and clay models – here a philosopher, there an emperor, over there a brace of saints – take up every inch of space and give the workshop a busy, crowded air, despite their individual stillness. He labours mostly in silence, or else with the radio in the background. “I can quite happily listen to The Archers,” he explains, “but if Wagner comes on, I down tools, sit and listen. You don’t work over the Sage of Bayreuth. Oh no. That would be a crime against humanity.”

On his desk are a vice, a hand-drill, a bottle of Macallan, and a well-thumbed copy of Robert Graves’ The Greek Myths. It is strange to see statues familiar, in their finished forms, from towns around Scotland gathered here in ghostly plaster. One striking work-in-progress is a 50ft monument to Adam Smith for a university campus in Dallas, Texas. Many of his commissions come from the United States.

People are sometimes surprised to hear that Stoddart lives and works in Paisley, as though the place were somehow beneath him or at odds with his love of beauty and order. But it is the town he loves and, as he says, “I’m a hardy provincial. I’ve always felt that great things come out of the provinces.” He always marks the word “Paisley” on his finished works, even when he does not sign his own name. The big cities, he feels, are decadent bastions of modernism; towns, meanwhile, have a greater respect for the tradition which he inhabits and embodies.

“Where you are from doesn’t need to be abandoned on account of some rise to fame or power,” he says. “People do express astonishment, and some think I cannot have made it because I am still here in the town. ‘Sandy had so much talent, but – ach – he just ended up in Paisley.’ When actually my work is going all over the world. But it’s not international renown you want, it’s local renown. If you can achieve that then you have really achieved something.”

He likes nothing better than to drop into his local, The Bull Inn, and be greeted by his familiar name – Sandy – by bar staff and regulars. Later, when we adjourn to the Bull, he points out the booth where his wife, a fellow redhead, was sitting when they first met, 30 years ago. The young Stoddart was, by his own account, “a screaming heterosexual”; however, he was in the company of a friend who was anything but, and so Catriona had some doubt as to whether this man in his early twenties who spoke in riddles and looked “like Byron” was boyfriend material. By the end of that evening’s lock-in, though, it had been determined that he was, and they now have three grown-up daughters – Clara, Sophie and Iona.

Advertisement

Hide AdStoddart, who is very sweetly not shy of sharing his feelings for Catriona, pulls a picture from his wallet and places it on the bar. “Look at this beautiful photograph of her. I show some guys in Italy this and they say ‘Bella donna!’ Her father was the second tallest man in Britain. Seven foot four and a half. The Bishopton Giant.”

Not being the sort to use as worn-thin a phrase as “soulmate” to describe their relationship, Stoddart explains that he sees his marriage in terms of Plato’s myth of the bifurcation of the soul – on some cosmic level he and Catriona were once one entity. More simply, he shrugs, “she’s the girl I love”.

Advertisement

Hide AdShe is not, however, his muse. That word, to him, is sacred. “No muse was ever somebody that you took out to dinner at the Rogano.”

Stoddart was born in Edinburgh. He and his younger sister grew up first in the Renfrewshire village of Elderslie and then Paisley. Both of his parents are still living. His father, Cochrane, was a graphic designer. His mother, Isobel, was the deputy head of Thorn Primary in Johnstone. He was brought up a Baptist and remains a Christian although not a church-goer. His paternal grandfather, Harry Stoddart, was a minister, known as The Boy Preacher, who could fill the Tent Hall in Glasgow with the draw of his oratory, and from whom, one assumes, Stoddart has inherited the gobby gene. His childhood was somewhat strict, though happy; the Sabbath was upheld – it was a day on which he would read The Pilgrim’s Progress and take long walks. “You couldn’t play with your bike, and you certainly couldn’t watch television, and you couldn’t play the piano unless it was hymns. I quite approve of it. I think the idea of children being made to be bored for a solid day once a week is very good for the spirit of invention.”

He dips into the New Testament every day, and is at present engaged in sculpting Christ and the 12 apostles for a private chapel in the south of England owned by a wealthy financier. The New Testament suits his temperament better than the fire and brimstone of the Old. “I was terrified as a child by the stories of Elijah and his chariot, Daniel in the lion’s den and all this. I was having nightmares about it. My paternal grandma, Nan Stoddart, a fine person, knew about this, so she got me a Broons annual and that did the trick. That took the terror out of it.

“I’ve been a great reader of the Broons ever since. I think it should be forced down the throat of every Scottish child. It will stand you in good stead for the rest of your life. It’s almost a toss up between The Broons and Virgil.”

Stoddart is, he insists, a very mild person. He has a horror of conflict. One would think, given his outspoken public statements on, to give one example, the proposed removal of the statues from Glasgow’s George Square, which he compared with the actions of the Taleban, that he rather enjoys being a controversialist. Not so.

“I hate all sorts of fighting,” he says. “I’m an absolute roaring pacifist. But sometimes you have to do it. When an assault is being attempted on George Square, that is a national emergency. Folk think I had a great time fighting about that, but in fact I was a bag of nerves. I lost time in my schedule. It’s upsetting, my skin pricks, I get all sorts of eczema and bowel problems. Terrible systemic collapse. Blood pressure sky high, of course. I hate being a controversial sculptor. I just want to be a working sculptor getting lots of jobs and plenty of chances to make beautiful objects.”

Advertisement

Hide AdHe seems to always be busy, and his work commands impressive fees – his David Hume was reported to have cost £120,000; James Clerk Maxwell more than double that – so the assumption is that he is a wealthy man. “The ‘millionaire sculptor’ Alexander Stoddart as was once said in the Paisley Daily Express?” he smiles. “It’s not true. We’ve got a huge overdraft. We’ve been very badly hit by the downturn, so-called… We also live beyond our means.”

Oh? What does he spend it on?

“Fine wines. Clothing.” He pauses to explain that his own tweed jacket was six quid from Oxfam. “The thing is, you see, I don’t like to deprive my wife of anything she wants, because she kept me going at the beginning on a registered mental nurse’s salary and as a student nurse before that. That’s real devotion. So we like to have a holiday, and we believe in breaking the sumptuary laws at every turn. As Bernard Mandeville said, private vice is public virtue. You’ve got a duty to be sumptuous, because if you do you’re keeping cloth weavers in Harris going, cigar-rolling mulattos in Cuba going, Ferrari builders going ... We are very, very devoted to jollity and conviviality and happiness.”

Advertisement

Hide AdHe has spoken sometimes about the “anaesthetic” and “narcotic” quality of art, the way it can ease the pain of both the artist and audience and offer a temporary release from a suffering world. When we first met he showed me a small clay figure of Hypnos, god of sleep, and explained that he had been feeling very glum and squalid until he made it.

Is he, then, someone who has dark moods? “Yes, terrible. Big slumps. I’ll be quite confidential with you, you’re seeing me rather in the middle of one just now.” He calls these slumps “the brown dog” and they are distinct from “the black dog”, an intense darkness from which he suffered when younger. “It’s verged periodically on having to go to the doctor. I wouldn’t say it’s clinical. But there is a momentary sense of complete and utter despair. Catriona will say, ‘Your problem is that you need to get some clay modelling done.’ She knows that it’s the best Temazepam that could be administered to me.” His wife, he once told the broadcaster Edi Stark, can tell when he comes home that he has been modelling angel wings – so lightened is his mood.

He likes the idea of his work being lost within the grand tradition of classical sculpture, so that it cannot easily be identified as being by his hand. He is not attempting to express anything about himself in his statues, but his choices of whom to sculpt do, of course, say something about what sort of man he sees himself as being and what he values. He wants to celebrate intellectual rather than physical achievement, which is one reason why he has never made a statue of anyone from the world of sport. This got him into bother a few years ago when he described as “infantile and immature” the plans to erect a monument to the rugby commentator Bill McLaren who had died not long before.

The truth is that sport makes him shudder; he was always picked last for school football and, even now, the sight of the All Blacks performing their haka, merely glimpsed on a pub telly, can give him the screaming ab-dabs. He did once attend a football match in Greenock, he confesses, and rather enjoyed himself, but this had more to do with the convivial journey by charabanc, the half-time pies, and the fact that someone in the crowd quoted Schopenhauer than anything to do with the actual game. He returned home to Paisley with his teeth full of mutton and a Morton scarf round his neck. “The girls were astonished and slightly appalled.”

He has definite ideas about who is fit to be immortalised in stone or bronze. No one living should have a statue built in their honour. Thirty years dead is, he believes, a decent interval. And God forbid that anyone – he mentions Thatcher – should have the poor taste to actually turn up for the unveiling of their own statue. Stoddart has an idea for a statue of a woman, the historian Agnes Mure Mackenzie, but takes no part in the discussion about women being massively under-represented among Scotland’s collection of statuary. He wants to carve the greats regardless of gender – “I’m not interested in the arrangement beneath their underwear.”

His fascination with art began in childhood. His father would, on Friday nights, spread paper on the floor and give drawing lessons. It was Stoddart’s mother, however, who first introduced him to sculpture, taking him to marvel at the monument to William Wallace in Elderslie, near their home, lifting the wee boy so that his head fitted inside the granite helmet. During the summer the family would make the long car journey north to Wick, to visit Isobel’s family, the journey enlivened for Stoddart by the sight of several stirring monuments along the way: first Wallace; then “Wee Peter”, the strange statue of the boy in Loch Lomond at Luss; then came the Commando memorial near Spean Bridge, and finally the statue of the hated Duke of Sutherland, high on his pedestal above the village of Golspie. In this way, on this route, the sometimes melancholy romance of history became linked in his mind with a memorialising instinct.

Advertisement

Hide AdStoddart, perhaps feeling rather underappreciated in our present age, cares about the judgement of posterity and does not want his art to be lost. He intends, he reveals, to leave the models and plaster versions of the whole body of his work to Paisley after his death, collecting them together in a “gipsoteque” – a sort of library of sculpture – just as his heroes Thorvaldsen and Canova did for their home towns, Copenhagen and Possagno. He thinks an old building, possibly a church, might be remodelled for the purpose. “It means, of course, that this material can’t be sold off at the end when I croak it,” he says. “It will deprive the family of some wee inheritance. But I think the kids realise that it is more important to keep it all together and do something for the town.”

He is a difficult man to figure, Sandy Stoddart. Generous, single-minded, cerebral, hedonistic, humble, narcissistic, a right gab who values silence. Sometimes he wakes up in the middle of the night convinced that he lacks talent. At other times he appears almost arrogant in his self-belief.

Advertisement

Hide Ad“Of course,” he says, cheerfully. “I’m a thundering egotist in some respects, and very vain, and paranoid. Pride is the problem. It’s the ultimate sin. As an old cleric once said to me, pride is the one sin that spits in the face of God. So pride has been my struggle. But remarkable as it sounds, I am actually human.”

• Making History, an exhibition concerning the making of the statue of Clio by Alexander Stoddart is at the Scottish National Portrait Gallery, Edinburgh, until September 28, 2014, admission free