Scotsman 200: Over 200 Royal Scots killed on their way to battle

Monday 24 May 1915

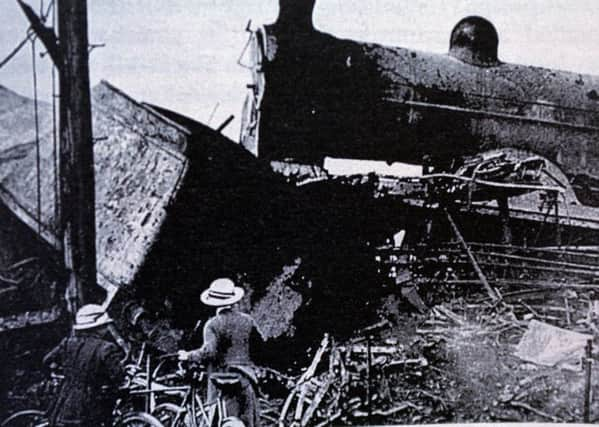

Troop train disaster at Gretna Green

A disaster that overshadows, in magnitude of scale and in painfulness of results, all that has hitherto been recorded in the annals of railway accidents in our islands occurred on the border of Scotland and England on Saturday morning. It may be questioned whether in the long and blood-stained story of the Debateable Land where the tragedy took place there is set down anything more startlingly and poignantly tragic than the fate which, in the course of a few minutes of shock and flame, practically wiped out of existence a half-battalion of the 7th, or Leith, Royal Scots. Of nearly 500 officers and men who were on their way from their homes to fight their country’s battle at the front, little more than 50 answered to a roll call – an incident as heartrendingly mournful as any recorded in Border history. The investigation of causes and the assignment of blame are matters that will engage by-and-by the public mind. Under the first stunning effects of the blow, the heart of the country, but more particularly of the district from which the victims of the catastrophe were drawn, has room for little else than sorrow. The destruction of a body that formed a complete half unit of the force detailed for the fighting of our battles is a national as well as a local calamity. The expressions of grief and of sympathy for the victims and for their relatives uttered by the King on behalf of the nation will be echoed throughout the land. But the sorrow and the suffering will come home most directly and most powerfully to the locality where have been reared of enrolled the bulk of the men who have been called to surrender their lives before being brought face to face with the enemy. More than one poor fellow gave vent, in his dying agonies at Gretna Green, to his regret that he had not been able to strike a blow, in the battlefield or in the trenches, for the flag under which he had enlisted. Their countrymen will remember them, and will cherish and preserve their names on Scotland’s roll of honour, as gratefully as if they had met death in front of the foe. Civilians also, of both sexes, were killed and mangled in the smash. But it will always be kept in mind as a grievous stroke inflicted by an untoward fate on the gallant regiment, the oldest in the British Army, which for more than three centuries has been closely associated with Scottish history and with the Scottish capital and its neighbourhood.

All the circumstances surrounding the Gretna disaster combine to make it one of the most painful episodes recorded in the civil or military annals of our land. To pain there is added, for the present at least, a measure of mystery. For the accident certainly took place under conditions which seemed to exclude all risk of a horror of the kind. There was not one collision but two; and keen and searching inquiry will be demanded into the question of how it came about, in the first place, that the troop train proceeding southward by the main line of the Caledonian Railway found at the critical moment a local train, bound from Carlisle to Dumfries, shunting across its track, and secondly why the express train from London to Glasgow, which came up at full speed a few minutes later and dashed into the wreckage, with results incomparably more disastrous than the original disaster, was not warned and stopped before the fatal spot. The engines of the troop train and local train, meeting head on, were both derailed along with several of the carriages. But the consequences might have been comparatively slight had not had not the express come up immediately after and dashed into the obstruction thrown into its path. The results were the most lamentable that could be conceived. The troops apparently had no time to or opportunity to get clear of the train in which they were travelling. They were involved in one common fate with the passengers of the local train and the express train. The wreckage occupying the two main lines caught fire, as the results of the impact and of the contents of the smashed gas tanks coming in contact with the engine fires. The piled-up mass of broken materials, including four engines, was transformed into a flaming furnace, in which the majority of the passengers, soldiers and civilians, were hopelessly imprisoned. To add to the hideousness of the situation, the collision happened at a point where help of any kind was not readily obtainable, the nearest house being a farm a considerable distance from the track. But it is doubtful whether, even if aid had been at hand, it could have done more than mitigate to a minor extent the horrors of the scene. The travellers who a few seconds before had been journeying smoothly towards their destinations on one of the brightest of May mornings, found themselves all at once face to face with death, in it most torturing and frightful aspect. There is but too good reason to fear that a large proportion, if not the majority, of the victims met the terrible fate of being burned to death while pinned down by the broken woodwork of the carriages. The bodies of the dead have in many cases been rendered unrecognisable.

Advertisement

Hide AdThe thought that will at once occur to the public mind is that some most deplorable error or defect in signalling must have been among the main contributing causes of the disaster. The question, and all the other material questions raised by the accident, will be strictly and thoroughly investigated. But while it would be wrong to prejudge or to distribute blame, it is not possible to forget that this, although the worst, is by no means the first calamity of the kind in recent years. In the present instance, not merely has the resulting loss been on an unprecedented scale, it is a loss directly inflicted on the Army, as well as upon the nation, at a time when sacrifices of the kind can least be spared. It lends an added pang to our grief to know that these precious lives have been flung away without any compensating result being achieved for the cause to which the soldiers had devoted their services. Finer heroism, however, may be shown in the face of danger that is sprung on men by surprise than in the battlefield itself; and no-one can deny that the five hundred who passed through the fiery furnace at Gretna have earned a title to the gratitude and appreciation of their countrymen, not less warm and lasting than is due to those who have stood or fallen in the firing line.

The full text of this edited extract can be found at The Scotsman Digital Archive