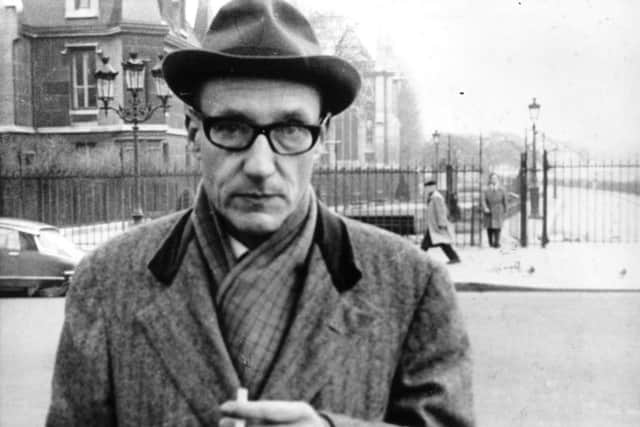

Scots literary maverick Alex Neish salutes heroes

FROM his apartment in Barcelona, the Scottish publisher Alex Neish is reminiscing about the time he rattled post-war Edinburgh’s literary elite by introducing them to the work of the Beat Poets.

As editor of the Jabberwock and Sidewalk literary journals in the late 1950s and early 1960s, Neish decided to shake up the staid Scottish publishing world by printing works of maverick writers, including Allen Ginsberg, Gregory Corso and William Burroughs. It was Scotland’s first glimpse of a counter-culture movement that was sweeping America.

Advertisement

Hide AdIn a rare interview, Neish told Scotland on Sunday: “I grew up in Scotland and had led a very parochial life so the Beat poets were a tremendous breath of fresh air. I thought they were really quite outstanding.”

Nearly 60 years later, Neish lives in Spain, in an extraordinary belle époque flat that was once the home of the painter Josep Maria Sert. The flat is crammed with books, art and his beloved collection of pewter. Slowed down by a recent brain haemorrhage, he still has the twinkle and the acid tongue of someone who doesn’t much care what anyone thinks of him.

Looking back at his time in 1950s Edinburgh, Neish recalls an austere city largely untouched by the outside world. Jabberwock, when he became editor, was, he says, dominated by “parochial nationalists who couldn’t see past their noses”.

Aware that there was a wider movement that rejected mainstream values taking off on the west coast of the United States, Neish decided to publish an all-American edition of the journal in 1959. “I published an American edition dedicated to the Beat Poets. There was no avant-garde scene in Edinburgh and I published them as a protest against the Scottish nationalists,” he says.

Among the work in that final edition was “And Start West”, the first chapter of William Burroughs’ then scandalous novel Naked Lunch, which Ginsberg had sent to Neish.

It is difficult to imagine the impact these writers had then. They were not only literary iconoclasts: Ginsberg was openly gay at a time when it was still illegal, Burroughs was a junkie, Corso had been in and out of jail since childhood. Along with Jack Kerouac, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, and others they were writing the obituary of the straitlaced post-war years.

Advertisement

Hide AdNeish, now 77, says he was drawn to the Beats for their artistic merits rather than their radical politics. “It would be difficult to repeat what they did because things that were revolutionary then are now things that we take for granted,” he says, adding “People aren’t interested in poetry any more. Perhaps the world has grown up. I don’t think singer-songwriters fill the same niche, although I think Bob Dylan is fantastic.”

He admires Ginsberg in particular and says: “One of the good things I did in my life was to publish Kaddish, which is an outstanding piece of work.” He believes this was the first time the work, a long poem Ginsberg wrote on his mother’s death, had been published in Britain.

Advertisement

Hide AdNaked Lunch he describes as “a ray of light” for someone “bogged down in Scottish prejudice and provincialism”.

The book was banned in Los Angeles and Boston when it was published in 1962, although the Boston ban was overturned after a hearing at which both Ginsberg and novelist Norman Mailer testified.

Mailer was also connected with Alexander Trocchi, some of whose work was published by Neish. Trocchi was an avant-garde Glasgow-born writer and member of the Situationist International. He was, like Burroughs, also a heroin addict. “Trocchi was a weird guy,” Neish says. “He was arrested in the States for supplying heroin to a minor and he was bailed out by Norman Mailer. Trocchi didn’t think he had a hope of avoiding jail so he went up to Canada.” In Canada he befriended Leonard Cohen and later returned to Scotland on a fishing boat.

All of this took place in a few brief years at the end of the 1950s. By 1962 Neish was gone, a voluntary emigrant from a Scotland for which he holds little affection. He spent the next few decades as a commodity trader in Argentina and Brazil, before retiring to Barcelona in 1994. He and his wife Patricia, whom he met at university, still spend their summers in Scotland in their Edinburgh mews house.

It was in Buenos Aires that he developed his passion for collecting pewter from Roman times onwards. In 1996 he donated what was by then the finest collection of British pewter in the world to the Museum of British Pewter in Stratford-upon-Avon. It has since been transferred to the Stirling Smith Art Gallery and Museum in Stirling.

Neish donated his collection of Jewish pewter to the Ancient Synagogue in Barcelona.

Advertisement

Hide AdNeish has no time for Scottish nationalism, which he derides as “totally ridiculous, because to my mind Scotland is an integral part of the UK”.

However, from his vantage point in Barcelona, he views Catalan independence more sympathetically. “I can understand it because Catalonia has an enormous cultural inheritance of its own which people are beginning to realise is very different.”

And Scotland doesn’t? He purses his lips. “I suppose it’s because the Catalans are more sympathetic people,” he says.