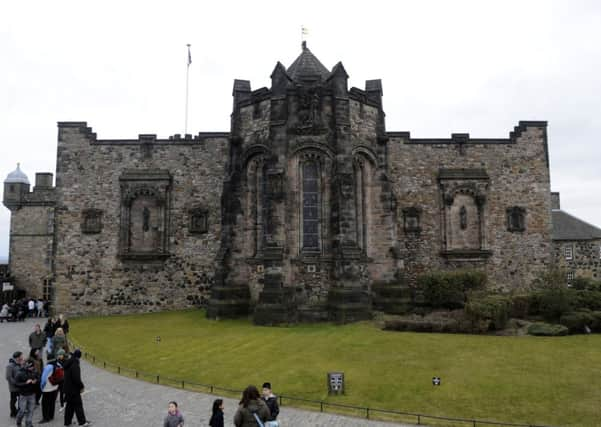

Scotland’s National War Memorial

The architect, Sir Robert Lorimer, led a team of more than 200 artists and craftsmen and the building includes superb sculpture and magnificent stained glass. Like the parliament 80 years later, the project was surrounded by fierce controversy, but once complete it was immediately accepted as a national shrine and was also widely recognised as a masterpiece of public art. The memorial includes all the names of the fallen of both world wars and subsequent conflicts too, but it was conceived, not as a monument to war, but as a way to express the fervent hope for peace after the terrible slaughter of the conflict of 1914-18.

Writing to Sir Spencer Ewart (General Officer Commanding, Scotland) on 17 August 1920, the Duke of Atholl (who chaired the committee that oversaw the building of the Scottish National War Memorial) commented on the public response to the proposed memorial and sketched out his understanding of the public’s priorities: “Old soldiers… value as you and I do the history of our regiments... but on the other hand you must remember that there is a great mass of people – more especially women who lost their relatives – who want to see a definite memorial.”

These men believed in the Union, and beyond it the Empire

Advertisement

Hide AdOne of the apparent puzzles of the whole story of the memorial is how a group of individuals like the Duke of Atholl and Sir Spencer Ewart, evidently unionists to a man, came up with a monument that is such a powerful focus of Scottish identity; indeed, through the records committee they actually set up and administered a set of rules for deciding who could claim to be a Scot and who could not. These rules were of course only applicable to those who had fallen in the war, but their implication is clear enough.

For all that these men believed in the Union, and beyond it the Empire, for them Scottish identity was not dissolved in that greater whole. It remained a tangible attribute of an individual and a source of pride. It is clear that for Atholl, as for many like him, the Scottish martial tradition was a vital part of their national identity.

The duke’s original proposal had been for a museum to commemorate those who had fallen, not only in the Great War, but also “in Scotland’s cause in former days”. In other words, it was to be a memorial to the whole Scottish martial tradition. In this letter, however, the duke recognises that this version of “Scotland’s story” is no longer adequate for the population at large. He had been fundraising tirelessly and speaking to many different audiences. He had clearly also been listening. His recognition of the real state of public opinion was the beginning of a shift that, in the end, led to him presiding over the construction of a memorial very different from the one he had originally envisaged. Indeed, Atholl saw very early on that what they were dealing with was much more than a war memorial. Writing to David Erskine, a co-opted member of the committee, in May 1919, he was clear on the matter: “If Swinton (Captain George Swinton was Secretary to the Committee and one of the prime movers of the project) and Spencer Ewart had their way, the Castle would become a receptacle for Army Lists and nothing else. They have none of them grasped that it is not only Highland Regiments we are raising a monument to, but something larger altogether.”

Kilts, muskets and claymores

It is significant too that Atholl also recognised how important it was that in this larger concept the memorial should reflect the sentiments of the women of Scotland. The inclusion of a monument to the women’s services was a very distinctive addition to the military monuments the memorial eventually contained, but, more than that, the sculptor Alice Meredith Williams (1877–1934) interpreted her brief for the monument to make it not just to the women’s services, but to all the women of Scotland. These things reflected the evolution of a more inclusive and more modern idea of Scottish national identity than the old imperial and military one of kilts, muskets and claymores. The memorial could not have continued to serve the nation as it has done if it had been otherwise.

In the minutes of the War Memorial Committee 702 local memorials throughout Scotland are enumerated. There were many more private and institutional ones, too. It seems unlikely, however, that they could often match the emotions of those who saw the names of their loved ones inscribed there. Indeed, in London the simplicity of Edwin Lutyens’s Cenotaph bears witness to the apparent impossibility of giving adequate expression to the nation’s grief, its enormity beyond any attempt to give it form. But there lies the difference, too. The Cenotaph in Whitehall seeks to be all-embracing as though by the sweep of a single gesture, while the Scottish National War Memorial does so by minute enumeration; it is inclusive of all the names of all the individuals, both men and women, who lost their lives and of all the units in which they served, but until Earl Haig’s small memorial was added after his death in 1928, no single person was named anywhere other than in the Rolls of Honour that list the names of the fallen.

A literary memorial to the war

In Sunset Song, Lewis Grassic Gibbon created a literary memorial to the war. He deals with separation and loss and with the situation of women left to cope alone without their men, as Chris Guthrie had to do. The book ends as the war ends; the trees, whose shelter had made the land cultivable, are cut down as the men were cut down in battle; without shelter, or the care of the men who had cultivated it, the land turns cold and bleak and can no longer sustain its people. Sunset Song was not published until 1932, but the intensity of one of the finest Scottish novels of the twentieth century and the richness of its author’s imaginative exploration of the experience of those left behind in the war and how they dealt with loss are a measure of the challenge faced by architect, Sir Robert Lorimer, and the Duke of Atholl. Their task, they realised, was not to offer false comfort to the nation and its people with tawdry myths of the glorious dead. No one could question the courage of those who went to their deaths against the guns, but there was little glory in such slaughter. The architect and his team had somehow to find a way to help the nation live with itself, its people find some mental peace in the face of their terrible losses, reconcile themselves to what had happened and so look through grief to a better future. That Lorimer and his artists rose to this task the memorial bears witness. In that it is unique, but it was not entirely without precedent. In Germany, a national Valhalla was commissioned by Ludwig I of Bavaria in 1826 and completed in 1842. It is a neoclassical monument very like the National Monument, or Edinburgh’s Folly, planned for Calton Hill at much the same time but never completed. Built before the unification of Germany, the intention was that in this Valhalla, German national identity should be embodied in its heroes, beginning with Arminius, the leader who had defeated the Romans.

A museum commemorating all of Scotland’s wars

Advertisement

Hide AdThere are certainly echoes of similar thinking in the discussion surrounding the Scottish National War Memorial. It was originally to be a museum commemorating all Scotland’s wars; and in 1919 in his initial report to the Memorial Committee, Lorimer suggested that the cloister he proposed as part of his scheme might be used for memorials to especially distinguished soldiers and sailors. Writing to Sir Lionel Earle, Atholl actually described Lorimer’s second scheme for the memorial (it was the third scheme that was eventually built) as ‘like a Scottish Military Valhalla’, and for some people at least, as a national shrine it did need a heroic dimension. It is to the great credit of Atholl and Lorimer that they eventually saw that their monument, while certainly conceived as a national shrine, had to meet a very different idea of national identity from one forged only in historical battles. Courage and indeed heroism, both sung and unsung, were central to the story, but the memorial was owned collectively. It was rooted in the present and immediate past, not in any more distant history. That was where its claim to be national lay. Although the idea of commemorating Scotland’s military history was part of the motivation that generated the memorial, in the face of the very different national sentiment that now prevailed, work on the military museum originally part of the proposed memorial was postponed. The memorial building itself became the sole focus, and in it the architect had to find a means of expressing a sense of loss, at once both collective and searingly individual; and somehow to assuage it with a sense of dignity, of fitness and, from these things, of pride, even in sadness and grief; above all, to present the hope of peace, the only outcome that might make the tragedy bearable. That was what Atholl and Lorimer eventually achieved, even if it was a struggle.

This is an edited extract from Scotland’s Shrine: The Scottish National War Memorial by Duncan Macmillan, published by Lund Humphries on 8 July, £40, www.lundhumphries.com