Review: Defining Beauty – The Body In Ancient Greek Art

Defining Beauty: The Body In Ancient Greek Art

British Museum, London Rating: *****

Neil McGregor is one of the most distinguished and influential Scots of our time. After ten brilliant years as director of the National Gallery in London, he could have rested on his laurels, but went on instead to become director of the British Museum where his 14 year tenure has been even more distinguished. The BM is a huge, unwieldy organisation, a supertanker among museums, but he has steered it deftly from the dangerous shoals of dowdy neglect to the wide, deep waters of international recognition. He is passionate in his belief that our museums are public property, a vital part of our shared imaginative and intellectual capital, and has now extended that idea to present the British Museum as a great international public property, a world museum. It is an extraordinary achievement. Nor would it have been possible if his vision were not matched by an acute political sense. Who else would have had a major exhibition on the walls restating Germany’s centrality in the history of European culture when Angela Merkel came to call? But that sounds opportunistic and that would be out of character. He is more subtle and a deeper thinker. Now he has announced his retirement characteristically against the background of one of the most important exhibitions of his career, Defining Beauty: the Body in Ancient Greek Art. It is not an exhibition he has curated himself, but is plainly shaped by his vision. No dry as dust art historian, he has constantly demonstrated that what justifies the existence of museums is not simply the preservation of the past, but the agency that the art they hold has in the present. That belief has galvanised the British Museum and it is typical of him that this exhibition presents one of the grandest moments in human history, yet is also urgently topical. The Greeks saw their gods in human form and this was the key to seeing divine beauty in ordinary humanity. In other ancient cultures nakedness was shameful. For the Greeks, the unadorned human body became a vehicle for ideals and a vision of human possibility. Bequeathed to us, the value thus placed upon our humanity has shaped much that has mattered most in Western history. Even Christianity, Hellenistic in so many ways, has at its heart the idea of god in human form.

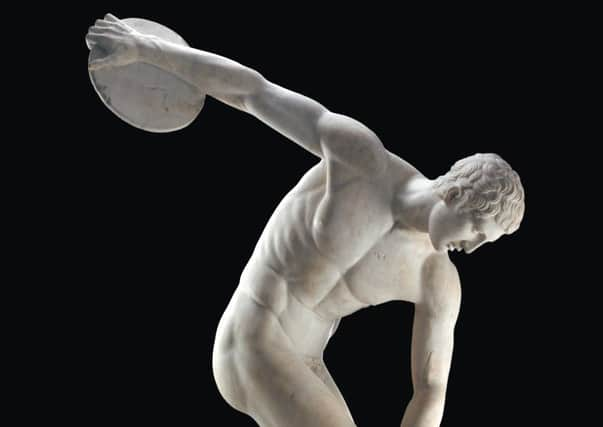

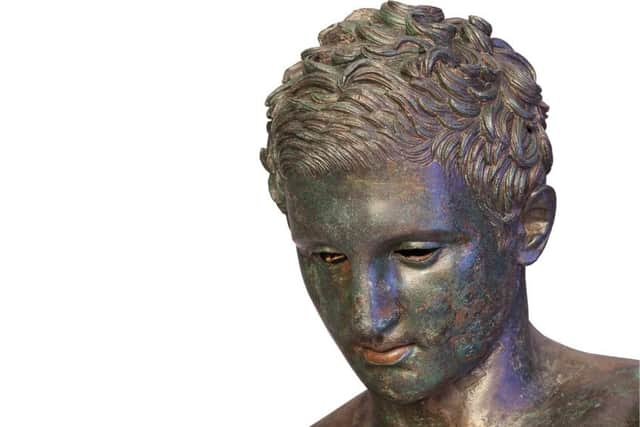

It was the great sculptors, Polykleitos, Myron, and Phidias, sculptor of the Parthenon, who laid the foundations of a human imagery that was wholly new then, but endures to this day. This triumvirate opens the show, Phidias represented by Ilissos, the beautiful river god from the west pediment of the Parthenon, Myron by a Roman copy of his Discobolos, or discus thrower, and Polykleitos by a 20th-century reconstruction of the lost male figure he designed with mathematically perfect proportions. These figures are very grand, but even so, a rare, full-size bronze outshines them. We are used to seeing ancient sculpture in marble and mostly too in Roman copies of Greek originals. The vivid naturalism of this athlete from the classic period of Greek art shows how much we miss, knowing only marble. Greek painting was equally vivid. Almost nothing survives, but some sense of what it was like is provided by vase painting, everyday articles on which art penetrated every corner of life and in which almost every aspect of life was in turn reflected. Greek sculpture was itself painted, however, but it is hard to believe that it looked quite so much like fairground decoration as attempts to recreate the original painted finish here suggest.

Advertisement

Hide AdThe colour was part of the Greek artists’ ambition to create a living likeness. Nevertheless, in Greek art monumental figures were not strongly individualised. The point of this is best seen in the long procession that once marched round the frieze of the Parthenon, Athenians on horseback and on foot on their way to some great civic festival. Several blocks from the frieze are presented separately and, seen close-to, it is clear how their individuality was less important than the fact that these people were part of the greater community that was the democratic city. Here, as in so many ways, the Greeks set a precedent which still matters profoundly. They gave form to the need to find the critical balance between individual and community, something we struggle to maintain in a world of spiralling inequality. The Greek model has been perverted by despots in the past. The Nazis thought they loved Greek idealism, for instance, but they also missed the point, for in its richness this exhibition shows how the Greeks had a humane vision of the whole of humanity, of the human race, not the master race, and indeed there are sympathetic images here of people from Sub-Saharan Africa.

The Greek ideal was originally military; men had to be fit to fight in an age of constant warfare. Heracles was half man, half god and so magnificently personified this heroic, masculine ideal, but the beauty of the wine god Dionysos was feminised and indeed men and women are here in equal strength. Women mostly stayed at home, but the goddess of love Aphrodite could be represented naked. She was, magnificently, and the female form became as celebrated as the male. Indeed, as you enter the exhibition you are greeted by a naked, over-life sized marble Aphrodite crouching with her back to you. Fluttering drapery carved with magical delicacy both conceals and reveals the female form of other monumental figures. Smaller figures, however, present ordinary women in a delightful, everyday light. This domestic world and strikingly too the world of children all found a place in Greek art. Indeed, images of children in sculpture and painted on tiny vases made for a child’s first taste of wine are the first celebrations anywhere of childhood observed in all its charm and innocence. The darker side of human behaviour was represented too, however, in images of battle, but also in satyrs and centaurs, their antics not to be condemned but enjoyed, as images of nymphs and satyrs having fun make clear. The erotic was part of life, both homosexual and heterosexual. When you drained your wine cup you might well find erotic images at the bottom to encourage the party mood.

But after these charming diversions, the climax of the exhibition dramatically drives home the main point. The figure of Dionysos from the east pediment of the Parthenon is set alongside the Belvedere Torso from the Vatican. The conjunction of these two figures is extraordinary anyway, but that is not all. The explosive energy of the Belvedere Torso inspired some of Michelangelo’s mightiest creations and so here alongside these two sculptural giants is his drawing for the figure in the Sistine Chapel of Adam stirring into heroic life at God’s command. In this drawing, by some extraordinary imaginative osmosis Michelangelo effectively recreates the art of the Parthenon which of course he had never seen.

At one level this exhibition could be seen as justifying McGregor’s argument that the British Museum is the best place for the Elgin Marbles. Only there can they be seen in this way as at the heart of world culture. No doubt that is true, but what this show does is far more important than join in an irritating local argument. At a time when humane Western values are under attack and, in adversity, we risk losing confidence in them, McGregor sets out for us, not only their origin, but their continuity, their place in the very wiring of the Western mind. There is nothing polemical here, however. The argument is from examples and that of course is uniquely what a great museum can do. It can give us the direct experience from which we learn without being told what to think. Brought together like this, all the wiring connected, their brilliance shines its light far beyond the walls of the museum.

• Until 5 July