Rescuing the reputation of composer Ivor Gurney

According to a doctor who treated composer and poet Ivor Gurney in a Dartmouth mental asylum during the psychological aftermath of active service and injury in the First World War, “insanity was there from the start, even without the Somme”.

It’s a question that has long exercised the minds of musicologists looking into the strange phenomenon of Gloucester-born Gurney, particularly as the music he wrote – principally songs – sends out the message of an artist immersed in the comfortable, inoffensive pre-war Edwardian world, with its propensity for long lyrical lines and a post-Brahmsian nostalgia tinged with the harmonic scent of confident Imperialism.

Advertisement

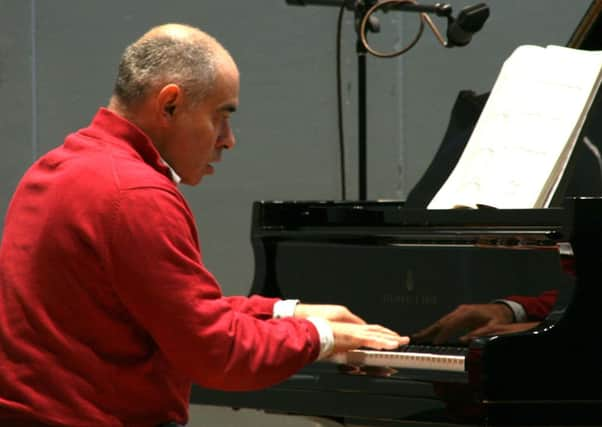

Hide AdAnd it’s a question that has long fascinated Glasgow-born pianist, accompanist and broadcaster Iain Burnside, who recently adapted his 2012 stage play about Gurney, A Soldier and a Maker, to be aired on Radio 3 on 29 June. The original play version first took root as part of Burnside’s research post at the Guildhall School of Music, where it was performed by a student cast, and revived subsequently at the Cheltenham Festival and London’s Barbican Centre. But its actual genesis was a close encounter with the composer as part of Burnside’s regular work as one of Britain’s most respected accompanists.

“I first became interested in Gurney when I was recording some of the songs for Naxos with the soprano Sue Bickley,” he says. “As preparation I bought a book of his letters, which were a complete revelation to me. I couldn’t quite reconcile the extraordinary primal energy, the hilarity of these letters – even when he’s writing in extremis from the trenches – with the polite Edwardian flavour of the songs.

“This in turn took me to his poems and a realisation that he was as valid a poet as he was a composer, and that there was a theatre piece lurking in all this material.” It’s a story he felt needed to be told.

Born in 1890, Gurney was the son of a Gloucester tailor, and he showed early promise as a composer, firstly as a chorister at Gloucester Cathedral, but more importantly as holder of an open scholarship to the Royal College of Music where he studied composition with revered traditionalist Charles Villiers Stanford.

Gurney’s eccentric demeanour had surfaced early – noticeable even in his childhood friendship with fellow Gloucestershire poet Will Harvey – and became an instant point of conflict with the hedonistic Stanford, who recognised a spark of genius in his pupil, yet also described him as “unteachable”. War intervened, and Gurney signed up to serve in France with the 2/5 Gloucesters, only to be wounded, gassed and shellshocked, forcing discharge and a period of recovery in Bangour military hospital in West Lothian in 1917, the same year his first volume of poems – Severn and Somme – was published.

Once recovered, Gurney re-entered the RCM, this time studying with Ralph Vaughan Williams, and in 1920 published his first volume of music, Five Elizabethan Songs. His return to Gloucester was not a happy one, and disillusionment over lack of recognition as either poet or composer immediately set in, leading to attempted suicide and committal to the City of London Mental Hospital in Dartford, where he eventually died from tuberculosis in 1937.

Advertisement

Hide AdBurnside believes that history has treated Gurney unfairly, or at least has failed to present the whole picture. “Although Gurney died the best part of a century ago, an awful lot of what he wrote we still don’t know,” he maintains. “There’s a huge amount of material lying in manila folders in a Nissen hut opposite Gloucester Rugby Club. The good news is that there’s a wonderful new biography by Kate Kennedy coming out, as well as a new edition of his poems. But there’s still a vast amount of unpublished work, mostly written in the asylum. I’ve seen some of it. It’s absolutely marvellous.”

Burnside recognises, too, the issues and weaknesses that led to institutional rejection of Gurney as a composer. “Even in the songs, which we tend to view as his finest music, you can see what he was trying to do, yet despite so much wonderful music, a lot of it doesn’t quite work.

Advertisement

Hide Ad“He probably didn’t want to be a song composer; he wanted to be writing string quartets and symphonies, to do the big stuff, but he didn’t really have the musical chops for it. Partly the war got in the way of his studies, but equally what turned out to be serious mental health issues also got in the way. He was a stroppy bugger; there’s no doubt about that.”

And isn’t it strange that someone so headstrong and determined – his capacity for work was immense – did not embrace the pastoral modernism of Vaughan Williams, the basis of which lay in the English folk revival? “You just wonder what could have happened if the whole English scene had opened up a bit more at the time he would have been open to it, or if he had followed Vaughan Williams’ lead and gone abroad to study with Ravel,” says Burnside. “That would have been very interesting.”

In many ways, the radio play, which features Richard Golding as Gurney, Stephanie Cole as his sister and Gemma Redgrave as his friend and mentor Marion Scott, answers that. Burnside pulls together a fascinating narrative built from many of Gurney’s letters and poems – a mixture of wit, abrasion and keen observation – and snatches of his finest songs, cleverly revealing the complex ambiguity of a personality moulded by a desire to be accepted among musical and literary peers.

One of the characters describes everything about him as “craggy, not polish”. His wartime comrades refer to him mockingly as “a private; his people are in trade”. We’re left with the picture of a man passionate about his art whose working class background – like fellow poet Isaac Rosenberg – was a barrier to acceptance; and of a composer whose inner torment curtailed his true potential.

• Iain Burnside’s A Soldier and a Maker is broadcast on Radio 3 on 29 June.