In pictures: Scotland’s lost motor industry

Our nation may be famous for its shipbuilding and engineering component construction, but it was also the home of Hillman Imp car construction, as well as the birthplace of Robert William Thomson - the inventor of the pneumatic tyre. Despite no longer producing cars, the nation’s automotive efforts have had a lasting effect on the industry.

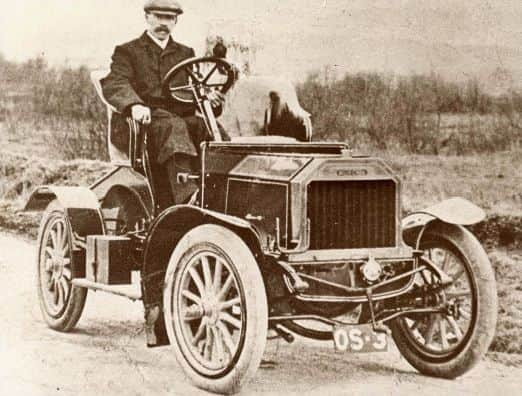

Founded at the turn of the 20th century, Arrol-Johnson represented Scotland’s first foray into motor vehicle construction. Locomotive engineer George Johnson partnered with Forth Road Bridge engineer Sir William Arrol, who bankrolled their syndicate’s “Dogcart” which first appeared in the 1890s. Drivers started the 10hp (10 horsepower), wood-bodied car by pulling on a rope which rose up through the floor, with production moving to Paisley after a fire ruined their original Camlachie premises. The company formally renamed itself the Arrol-Johnson Car Company Ltd in 1905 after a takeover and management reshuffle led by industrialist William Beardmore.

Advertisement

Hide AdNumerous revisions of the original Dogcart appeared until the company bought land near Dumfries to build a new factory. Inspired by American assembly line practices and designed by Albert Kahn - the designer of the Ford Model T factory in the USA- the factory produced the unreliable “Victory” model at the end of World War I, which led to the reintroduction of pre-war models. Further refinements and a merger with Aster were not enough to stave off declining sales and Arrol-Johnson finally ran out of fuel in 1931.

Where Scotland failed with motor car manufacturing, it found greater success in the manufacture of industrial vehicles. Albion Motors still exists to this day as part of American Axle & Manufacturing, after escaping the nervous years of British Leyland ownership in the 1970s. Founded in 1899 by two previous Arrol-Johnson employees, the company’s fifteen-year attempt to make passenger cars was superseded by its lorry and bus efforts. Popular chassis included the Chieftan, Clydesdale and Viking lorries and buses, before a wholesale change to the sole manufacture of automotive parts was effected in 1980. The company’s solid engineering even extended to fire engines which saw service across Britain.

Completing Scotland’s “Three A’s” of automotive construction was the Argyll marque, which was founded at the same time as Arrol-Johnson in the late 1890s. The first Argyll Voiturette copied a Renault design which provided a maximum of 10hp after many revisions. After the company’s ornate, purpose-built Alexandria factory was sold to the Royal Navy at the start of World War I, the company entered a decline before closing in 1932.

Unlike Albion or Arrol-Johnson, Argyll got a second chance at success when it was resurrected as a sports car manufacturer in 1976. With the Argyll Turbo GT made in a factory beside the old Arrol-Johnson works in Dumfries, the spectacular-looking wedge-shape used a fiberglass body and a Renault-derived V6 engine. However, with a high purchase price and ill-fitting parts derived from Triumph, Datsun and Volvo models, the Scottish sports car never really competed with contemporary rivals such as the Porsche 911 or Ferrari 308 GTB and was a commercial flop.

Perhaps Scotland’s most famous contribution to the motoring world came in the form of the Hillman Imp. Manufactured by Rootes Group, the Imp was a response to the small-car boom of 1960s Britain after the Suez crisis and hike in fuel prices. The Linwood factory to the west of Glasgow was created after government pressure was put upon the company to create jobs in an area of high unemployment, with over 440,000 cars made by the time production ended in 1976. It was a radical design for its time, with its aluminium rear-engine canted at 45 degrees.

However, the Imp’s story wasn’t plain sailing, with several high-profile industrial disputes interrupting the car’s production run. In 1964 alone, there were 31 stoppages with only 50,000 cars produced in a factory capable of manufacturing 150,000 units per year. The mass recruitment of ex-shipbuilding workers, while technically skilled, would underpin the basis of souring relations between management and workers during this period. In addition, the badly-regulated quality control standards meant that the Imp soon gained a reputation for unreliability with drivers. Linwood was sold to Peugeot-Citroen in the early 1980s, who then decided to axe the plant and its accompanying steel mill altogether.

Advertisement

Hide AdEleven year-old Alexander Dennis is a prime example of 21st-century Scottish engineering, as the bus-making concern enjoys huge sales in Europe, North America and the Far East. The Falkirk firm’s dominance of domestic bus networks is well-documented, with the company achieving a staggering 47% UK share of the UK’s new bus market share in 2013. It remains to date one of Scotland’s most successful automotive companies on record.

So how did Scotland do overall in the motor vehicle business? Grampian Transport Museum Curator Mike Ward said: “At the dawn of the motoring era Scotland was near the top of the tree with the famous “Three A’s”; Argyll, Arrol-Johnston and Albion. The Argyll factory at Alexandria was among the most modern and palacial in the world. These were award winning cars that won races and cornered markets in the very early years.

Advertisement

Hide Ad“Scotland was off to a good start but did not sustain the position in the face of the booming worldwide car making industry. Every car maker shuddered once Henry Ford’s Model T hit world markets in 1908 but Scotland’s industry collapsed during the Model T’s production run.

“Linwood in the 1960s was a brief revival of hope for volume car production in Scotland but the Rootes group’s Hillman Imp could not match the incredible sales of the Austin Morris Mini and Linwood limped into early closure. The Linwood story is one of high hopes and great disappointment for the new workforce that still haunts the Paisley area.”