Photographer David Eustace on his new Scottish show

Photographer David Eustace is talking to his twentysomething self. “If you don’t go up to that guy and ask him if you can take his picture, you won’t be taking a 1,300-mile road trip across America with a daughter who hasn’t even been born yet, and you won’t be given $80,000 to do it.

You won’t be photographing Paul McCartney, Sophia Loren or John Mills, going to Brazil, Beirut or Asia. You won’t be doing any of that if you don’t take that first step. So go on, go on...”

Advertisement

Hide AdThe busker was standing at his patch on the corner of Bath Street and Renfield Street in Eustace’s home city of Glasgow back in 1992, and the newly-graduated photographer was willing himself to cross the road and ask him to pose for a portrait.

“He was ring-a-ding-dinging away and it was like a comedy sketch. I’m thinking, ‘I’m going to ask him, but what if it’s a no? Should I? What if it’s a no? Should I?’ I was going back and forward like a yo-yo, asking all these questions and they were all negative. I was thinking of everything that could go wrong. But eventually I walked across the road, asked him and he said yes, I took the shots and then some more, and it became a body of work called The Buskers.

“Fast forward 20 years and the creative director of Anthropologie sees these pictures then commissions me to photograph a road trip across the US with my then 17-year-old daughter Rachael. The point is, if I hadn’t taken that first step, none of those other things would have happened. We do things that won’t mean anything for another ten years but that’s where they come from. We do things that aren’t for tomorrow,” he says.

“Nothing is going to happen unless you do something. That’s what I tell students starting out now. You don’t know what’s around the corner and it’s not always the immediate thing. Everything comes full circle.”

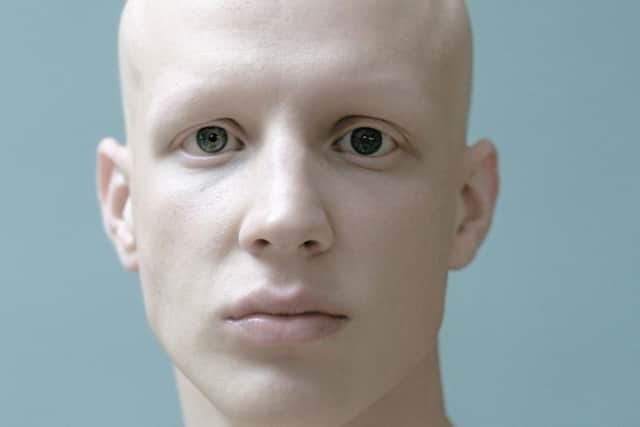

Eustace is big on things coming full circle, and so it is that he finds himself back in Edinburgh, where he was born and where he trained, for an exhibition, David Eustace at the Scottish Gallery in Dundas Street. His first major show in Scotland for 15 years, his work will be on sale to the public for the first time. Comprising around 50 images that will be available as limited editions, it will include selected works from his recently published retrospective book and work from his portraiture, travel and landscape images that will give a snapshot of a career that also sees him shooting commercials and films.

I write to you of a baby boy born only yesterday

“I will make the final choice the day before. Some on the day, but it will include some of The Buskers, the Weir Group shots, Beirut and Beyond pictures, some of the 50 faces from the American Character US road trip, something from the road trip In Search of Eustace with my daughter Rachael, images of Scotland from the Highland Heart Portfolio, pictures from Burma, China, Brazil, George Mackay Brown, Eve Arnold, Harry Dean Stanton, John Byrne, John Hurt …” The list goes on.

Advertisement

Hide AdThe title of Eustace’s book, I write to you of a baby boy born only yesterday, is taken from a letter to his adoptive parents telling them of a baby they might be interested in. The baby that was to become David Eustace.

“The book was about my life,” he says, which started when a girl from the Highlands gave up her baby for adoption and he wound up with a couple in Glasgow.

Advertisement

Hide Ad“It sounds more melodramatic than it was. I remember asking my mother for money to go and play football and back in the early 1970s anything of importance, the woman of the house kept in her handbag. When I was in there getting the money I remember finding this letter. It was dated 24 November 1961, the day after I was born so I knew it was about me. It wasn’t a big surprise and it wasn’t a major thing in my life. I went out and said to my mates, ‘I’m adopted’. And they said, so f**k, you’re still in goal.

Eustace felt no urge to trace his birth mother until after his adoptive parents had both died.

‘We could all make a connection where you can affect people’s lives’

“I thought I had parents, I didn’t need a second lot. It never affected my life again until I was 38, about ten years after my parents had died, and I still had the letter. I knew she was just a young girl, and I didn’t know if she was alive. She could be the Queen of Sheba or a two-bit hooker. I just wanted to let her know that everything was OK. It was OK.”

Eustace says the book is also about how you can make a connection that can affect other people’s lives. “That explains about me. We could all make a connection where you can affect people’s lives.”

For him, one big connection, one that feeds into his sense that life is always coming full circle, was when he re-established contact with his birth mother.

Advertisement

Hide Ad“Sometimes worlds collide,” says Eustace. “Meeting her changed my life because it changed other people’s. The greatest thing for me was that that young girl knew that her baby had no regrets or anger. Of course, it could go the other way, your mother might not want to know, and that could be brutal. But for me, it wasn’t. I get on well with her now. I was up north with her last weekend.

“She was 20 and went to the doctor feeling sick, and he said you’re not sick, you’re pregnant. She didn’t want to bring shame on the family so she went to Glasgow, got a job as a cleaner, then a week before I was born, went through to Edinburgh. She said if you’re going to be adopted I want you to get a better chance – Glasgow was chaos in 1961. So I was born in Edinburgh. Then two days later I was taken to Provanmill,” he laughs.

Advertisement

Hide Ad“But I had THE BEST upbringing. The most brilliant upbringing.”

Raised in Glasgow’s East End, Eustace is no-nonsense, honest and direct. Straight talking. He has a reputation as the photographers’ photographer.

“There’s a side to me that’s very open and I say what I think. They didn’t know what to make of me in America at first, their jaws would drop. I didn’t know what a cappuccino was until I was 28,” he says, sipping a soy latte. “It was another world. Before that I knew the street and what was surrounding me. But I’m the same person.” As he lifts his cup and notes the cute heart sculpted into the foam, several thick silver chains on his wrist jangle. “Remind me of the jail,” he jokes. “No, I just like them.”

‘That’s me, Armani jacket but steel-toecapped trainers’

With his shoulder-length hair and beard neatly styled, and a smart Armani jacket over jeans, the 53-year-old looks the picture of success when we meet in a basement cafe in Edinburgh’s New Town. A cold bright morning, the wind swirls flakes of snow down slippy steps and I notice his trainers.

“Steel toecapped trainers, from Screwfix. £19.95. That’s me, Armani jacket but steel-toecapped trainers, 19 quid.”

Steel toe caps?

“Yes, we’ve just bought this old house, and it’s a building site. I had a lovely house in Glasgow and a flat in Edinburgh and we paid them off and my wife Deirdre took early retirement. But then we take on an old house and there’s water pishing through the ceiling and the old boiler needs replaced and there’s asbestos. But I have never lived in the comfort zone. I follow my gut.”

Advertisement

Hide AdWhen Eustace left school, his various jobs included selling fruit on a market, bingo calling, serving on minesweepers in the Royal Navy, before he became a prison officer at HMP Barlinnie for seven years.

“The jail was brilliant, I enjoyed it. There were difficult days, when you might walk in and find somebody hanging, or running at you, and there were good days. It was 70 per cent boredom, 20 per cent hysterics and 10 per cent sh***ing yourself. I’m friendly with a lot of the guys from jail, and the guys that did time. I never sent them to jail, I was there to stop them getting out. You don’t become hard, you become hardened. I only realised the effect it had had on me when I left.

‘The job made me non-judgmental I think’

Advertisement

Hide Ad“The job made me non-judgmental I think. I never judged anybody because they were doing time. I might have judged them because they were an arsehole, but I would never made any preconceived judgment.”

At 28, he picked up a camera for the first time and never put it down. The following year he was accepted to study photography at Edinburgh Napier University and before graduating with distinction three years later, he was already receiving commissions and within a short period of time, his images were being seen in GQ, Vogue, Elle and the Sunday Times. Why does he think he hit the big time so fast?

“Dave Stewart [of the Eurhythmics] said you foresee no problems, and I never did. I knew who I wanted to work for. I graduated in 1991. By 1992 I was at Condé Nast. I just went to see them. I had given up a good, secure job at the jail to go back to further education and Deirdre was working as a teacher keeping a roof over our heads. People had made sacrifices,” he says.

“And I was so grateful to get accepted. I had three years of being a student and we were broke, never had a pot to piss in. I don’t want to exaggerate because there are people who are starving, but we would have a pot of soup and that was it. It was bonkers, but it wasn’t a hardship because we wanted to do it.

“I would work 20 hours a day in a dark room and get the light right. I loved every moment of it and it was what I wanted to do. Sometimes I would think, I should go and get a job in the jail again, but in the final year, I knew the people I wanted to work for.”

What did picture editors see in Eustace, a new graduate from Napier?

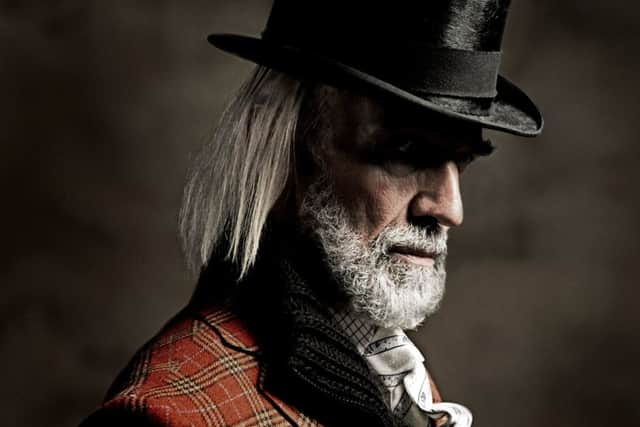

Advertisement

Hide Ad“This thing that just walked in from Glasgow that they weren’t quite used to. I don’t know. Grant Scott at Elle described me as a cross between Billy Connolly, Catweasel and an Australian backpacker. I made my own prints, I was there with my book, I went to see them. It was just, here I am. I had no agenda, no plan.”

Eustace cites his influences as Martín Chambi and August Sander

Advertisement

Hide AdEustace cites his influences as Martín Chambi [an indigenous Peruvian Indian photographer] and August Sander [a German photographer who documented ordinary people in 1920s, 1930s Germany] whose work is as much social commentary as art.

“It was something more than their photography,” he says. “And Irving Penn, Avedon, Albert Watson, I kept seeing their names but I never knew anything about them. In my final year I went to see Isabella Kullman, picture editor at Vogue, and I asked her about Albert Watson. She said, he’s Scottish as well. I didn’t know!

“So I sent off some slides to him in New York, then I phoned and he was coming over to Scotland and needed a driver/assistant. He said why are you an assistant? You should just be taking photographs. He said next time you’re in New York, pop in and see us. There was more chance of me being on Mars.”

But then, once again, Eustace made one of these life-changing connections. “Seven years later I was in New York for the first time – I was like a dog that’s found its tail – looking for an agent and I thought I wonder where Albert Watson’s studio is. I knew it was Washington Street. I looked up and I was standing outside. So I pressed the buzzer. He remembered me and that was it. He said, we are representing you now. Worlds collide. Things come full circle.”

There’s no mystique, just hard graft

Ask Eustace about his technique and he’s refreshingly jargon-free. There’s no mystique, just hard graft and he’s happy to admit he makes mistakes.

“I just don’t show them. Photographs are an encounter of two people. You are hoping everything connects. I don’t try and capture the soul of anybody. I’m not interested in that. I’m hoping to do a relatively honest portrait. You have to have faith that the portrait will find itself. I’m often not quite sure what I’m doing, but that’s what’s interesting. You find interesting things everywhere all the time. For instance, I’m here with you now having a coffee, by a window and I’d photograph that bit behind you. That shape, it’s interesting. Move your bum closer to the window.”

Advertisement

Hide AdI pass him my iPhone and he takes the picture. I’m half in, half out of the shot, with vertical lines in shades of grey and blue. The light catches my laughter lines and for once, I have a picture of me I like.

“Taking photographs is not that difficult,” says Eustace. “What is difficult is convincing people it’s a great photo. Sometimes you don’t see something until after. Like in the Highway 50 project of portraits. There was one man I didn’t take to and after I saw it in the photograph he was surrounded by stuffed animals, howling. Then with Alan Cumming, he was looking down and looked so sad, but you have to go with that. He loved that picture later. It was about his father. He was having a nervous breakdown.”

Advertisement

Hide AdEustace has captured more than his fair share of well known faces, but for him, whether they’re a celebrity or not is immaterial.

“Someone once said to me you can shoot a young girl in Beirut and the way she looks at you is the same as Paul McCartney,” he says. “They will bring a different performance to the person in front of them, but that person is me. And I bring myself. It’s not bang, bang, bang. You have made a connection.”

He’s photographed McCartney a lot, is he a friend?

“He’s not a friend, I don’t make relationships like that. Somebody like Paul McCartney, they are constantly on the move doing a thousand projects. He’s not a friend, it’s more mutual respect, as artists. I have travelled all over with him and he’s a legend, yes, but he has something more.

“Sophia Loren, is like that too. She has presence, like Paul McCartney, but their substance as human beings has never changed. She was adorable. She told me that coming from Naples, she was always in a black dress because you could get another day’s wear out of it. Later, I was out and my wife was making dinner and a lady phoned asking to speak to me. She said it was Miss Sophia Loren and she wanted to say thank-you for the photographs.

“I don’t do celebs. I don’t see them as that. People I have been lucky enough to work with are not celebs, they’re more long term.”

Now, after years splitting his time between New York and Glasgow, Eustace is back in Edinburgh where he has settled with Deirdre and Rachael, who is studying fashion at art college.

I have been very fortunate and made some money

Advertisement

Hide Ad“I have been very fortunate and made some money but for the last 15 years I have been six months here and six months there. I want to spend more time here, get involved more in companies in a creative sense. I will never find a city that inspired me more than New York, but the level of photography there in terms of commissions, there are too many third party involvements.

“I’m doing other books at the moment too, and they will depend how I write to tell you of a baby boy born only yesterday does. There’s a Friends and Artists one, another of small observations and snapshots that will be called Love Letters. Hopefully Paul McCartney will write the intro. And I’d like to take more pictures. Still lifes, a set of nudes, the Friends and Artists with a 35mm camera.

Advertisement

Hide Ad“I want to do more with my life. Yes, I want to take more pictures.”

• I write to tell you of a baby boy born only yesterday is published by Clearview, £60.

David Eustace at the Scottish Gallery, Edinburgh, 4-28 February. Limited edition prints from £1,200-£4,750, www.davideustace.com