Old Aberdeen's crazy paving plan '“ wood you believe it?

But a new book exploring the history of Aberdeen’s famous granite trade has revealed how, at the industry’s height, the city’s fathers carried out a failed experiment that saw some of its pavements relaid with wood.

With around half of Aberdeen’s cityscape estimated to have been built using stone hewn from Rubislaw quarry, it has long stood as a proud advertisement for the granite it sent the world over.

Advertisement

Hide AdIts stone paved the streets of London, formed the terraces for the Houses of Parliament and created lighthouses in the dark, inhospitable expanses of the North Sea.

But author Dr Michael Dey points out even as Aberdeen was making its name as the granite capital, authorities were against using it on local streets.

In The Granite City, which explores the genesis and evolution of the industry, he reveals a mid-19th century Lord Provost of Aberdeen championed the unlikely idea of using wood paving.

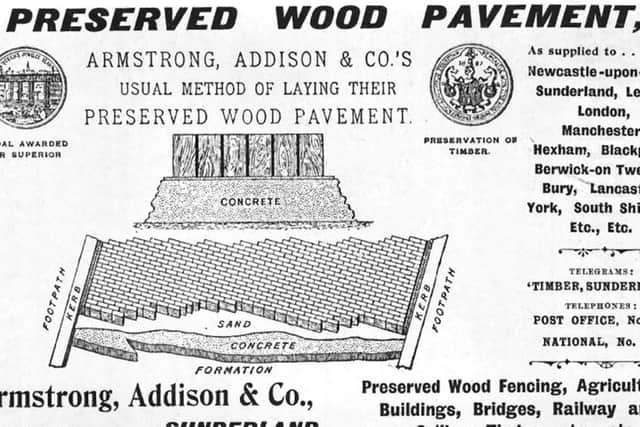

In a break with tradition, the material had been used in London’s Oxford Street and outside the Central Criminal Court, winning plaudits for the way in which it deadened street noise.

By 1843, Dey said, Sir Thomas Blaikie thought Aberdeen should follow suit, having paid a pleasant visit to London. The sight and – much reduced – sound of the “wood pavement”, noted Sir Thomas represented a “great improvement” and “stood admirably”.

The proposal drew the ire of fellow councillor Alex Matthew, who argued “the board ought to be the last to go into this expensive paving”, warning it would ruin Aberdeen’s principal trade.

Advertisement

Hide AdBut the Provost won the day and, as an experiment, wooden blocks were laid on St Nicholas Street. As Dey points out, it was to prove short-lived.

“Over the rest of the decade it became clear that wood was not a serious challenge to stone,” he said. “Apart from the claim that sodden wood gave off unhealthy vapours, it was found that for all the assertions made by manufacturers, and despite the variety of shapes available, the useful life of wooden cubes was significantly less than granite.”

Advertisement

Hide AdDey’s book, which explores how Aberdeen granite became the stone of choice not just for architecture, but great engineering projects, also pinpoints a sense of anger and resentment in the city over how pavements and streets were left to fall into disrepair during the granite trade’s halcyon years.

While the north-east’s economy was bolstered by the hard-wearing material, there was discontent at home over how Aberdeen’s thoroughfares were made up of little more than pebbles and dirt.

At in the industry’s height in 1817, 22,167 tonnes of granite was exported to London alone. But Dey points out while granite was viewed as a “fine” solution for other cities, it was “usually a bit beyond the pocket of local ratepayers” in Aberdeen.

As late as 1869, the granite manufacturer Macdonald & Field complained of how Constitution Street was in a “wretched state”, as was nearby Virginia Street.

The Granite City: Aberdeen’s Granite Industry is published by Amberley Books.