Movie review: Magic Mike XXL | Amy

Magic Mike XXL (15)

Directed by: Gregory Jacobs

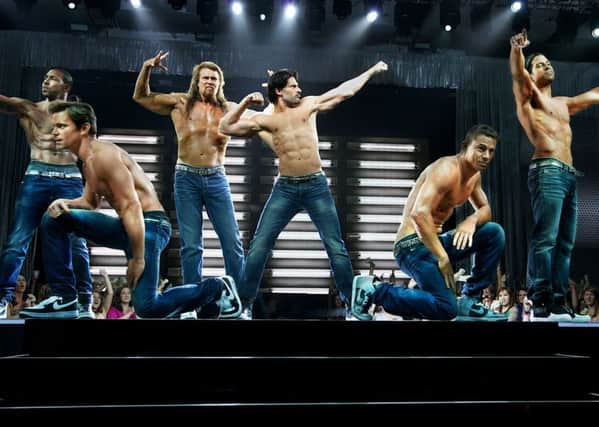

Starring: Channing Tatum, Joe Manganiello, Adam Rodriguez, Andie MacDowell ***

The resulting film – based loosely on star Channing Tatum’s days as an exotic dancer – became a monster hit, so it was only a matter of time before it spawned a sequel. Magic Mike XXL is that film and while the super-sized promise of its title doesn’t take into account the loss of Soderbergh (mostly) from the director’s chair and Matthew McConaughey from the strippers’ stage, the film nonetheless makes an attempt to maintain that curious mix of reality and fantasy the first film pulled off so well.

Advertisement

Hide AdThe film begins quietly with Mike (Tatum) trying to make a proper go of the furniture business he left stripping to set up at the end of the first film. He has a lot on his mind: his girlfriend, Brooke, no longer appears to be in the picture and while his business is doing OK, he’s barely able to pay the healthcare costs of his one employee. So when he gets a phone call from his old crew, The Kings of Tampa, informing him that they’re heading to a stripper convention for one last hurrah, he finds himself unable to resist the allure of a final blowout with his preening, narcissistic friends.

As plots go, this is as thin and as stretched as one of Mike’s gold lamé thongs, and the road movie set-up certainly doesn’t inspire much confidence that this will be as entertaining or as dramatically compelling as the rivalries that drove the first film. Which initially proves to be the case. In embracing the lets-get-the-gang-back-together-and-put-on-a-show plot device, director and long-time Soderbergh collaborator Gregory Jacobs aims for the breezy camaraderie of the Oceans sequels. Tatum aside, he doesn’t have the star power to cover the cracks, so to speak, and it takes a while for the supporting cast from the first film to really establish themselves here as this film’s stars, though in truth, only Joe Manganiello as “Big Dick” Ritchie distinguishes himself enough to emerge from the baby-oiled pack.

That said, the film does start to get funnier when Mike – bored of tired old routines involving firemen and construction workers – gets the individual members of the troupe to explore their own desires and feelings in order to come up with routines that are truer to their own personalities. The film also plays around with gender issues in ways that are quite interesting for a mainstream movie: setting up the main cast as vacuous eye-candy whose increasing awareness of their own ageing bodies and fading looks have made them more sensitive and genuinely appreciative of their female clientele.

Along the way there are some strange plot turns that keep things unpredictable. In an amusing callback to Sex, Lies and Videotape, Andie MacDowell pops up as a rich, frustrated divorcee who welcomes Mike and his friends into her home to entertain her and her wine-quaffing friends. There’s also a stopover at a mansion run by former female employer of Mike’s (played by Jada Pinkett Smith) whose business offers women the opportunity to boost their self esteem via hits of crotch-grinding action from teams of strippers.

The final stripper convention is similarly bizarre: a haven for Twilight-inspired stripper fantasies and wedding routines sound-tracked to Nine Inch Nails songs.

What makes it work in the end is the way Jacobs strips away the surface blockbuster gloss. Deploying Soderbergh as his cinematographer (he’s credited under his usual pseudonym, Peter Andrews), the new film might lack some of the depth of the original, but its unwillingness to glamourise a ridiculous profession by exposing its tawdry nature also gives it a weird nobility that’s kind of endearing given all its practitioners can really expect in terms of financial rewards is a “tsunami of dollar bills”.

Advertisement

Hide AdTatum also aids the film in no small way here. Save for the occasional tongue-in-cheek acknowledgment of the film’s cheesier tropes, he plays things admirably straight, fully aware of what audiences want and delivering little bursts of fleet-footed magic here and there to reassure everyone they’re in for a good time. And all Mike’s magic really is Tatum’s too: an early riff on Flashdance featuring Mike in his workshop gyrating along to 1990s R&B sets the tone for the insane bouts of floor-humping, ass-thumping, crotch-pumping action that follows. He’s this unlikely franchise’s super-sized star.

AMY

Directed by: Asif Kapadia

****

Amy Winehouse was already on a downward spiral when her second album Back to Black made her a household name and an easy target for anyone – comedians, the public, the mainstream media – hungry for salacious stories of rock n’ roll excess. What got lost amid the headlines that plagued her for the few short years she dominated the British and international music scene was just how talented – and how ill – she really was. That makes Amy a welcome and much-needed corrective. Directed by Asif Kapadia in a style similar to his game-changing Senna, the film eschews the talking-head format to reconstruct Winehouse’s short, troubled life through a wealth of home movies, archival footage and news reports – all contextualised with painfully raw and reflective testimony from family members, friends, colleagues, many opening up for the first time about the Amy they knew.

Advertisement

Hide AdWhat emerges is a portrait as intimate as the use of her first name in the title implies. That it’s sad and tragic almost goes without saying: like so many true artists before her, she really wasn’t cut out for the celebrity that accompanied her stratospheric success, neither of which were goals in her life. As the film makes clear, she really just wanted to be a jazz singer; the circus that erupted around her was a byproduct of her talent and hard-working determination to make great music, something that created a bit of a disconnect when the mainstream embraced her music without necessarily understanding where she was coming from or what she was trying to do.

Her music was deeply personal and one of the most astonishing things about the film is the way it shows just how closely her songs correlated to her life. Kapadia frequently juxtaposes conversations Amy had with performance footage, flashing the lyrics up on screen to show just how verbatim some of these lyrics were in terms of reflecting where she was mentally and emotionally at a particular moment in time.

When the addictions and troubled relationships start to exert their grip on her, the film really comes into its own, showing the painful reality behind the flashgun assaults from the paparazzi and the goldfish bowl scrutiny she faced on a daily basis. It also serves as a fascinating document of our changing relationship with technology: the preponderance of reality television and advances in camera phone technology have a visible impact within the film on the way her life was recorded and documented. Of course Amy isn’t naïve enough to suggest she was some kind of innocent victim in all of this, but it does offer a subtle indictment of the hypocritical and pious nature of a culture that creates the demand for the kind of tragedy Winehouse was clearly hurtling towards.

Magician: The Astonishing Life and Work of Orson Welles (12A)

Directed by: Chuck Workman

***

“I represented the terrible future of what was going to happen to that town,” says Orson Welles in one of the many archival interviews utilised in this entertaining but hardly radical primer on Hollywood’s first real auteur. The quote is in reference to his arrival at RKO ahead of making Citizen Kane. His desire for complete artistic control prefigured what would become an ongoing struggle faced by all directors interested in making art in an industry that worships commercial success above all else.

The film runs through all the expected biographical highlights and while there appear to be very few new interviews, friends and admirers such as Peter Bogdanovich, Martin Scorsese and Steven Spielberg offer some entertaining insights, while Richard Linklater (who directed Me and Orson Welles) is on hand to discuss Welles’s status as the godfather of independent cinema.

The First Film (PG)

Directed by: David Nicholas Wilkinson

**

Advertisement

Hide AdFor 30 years director David Nicholas Wilkinson has been obsessed with proving that cinema began not with the Lumière brothers or Thomas Edison, but with Louis Le Prince, a Yorkshire-based Frenchman who patented a single lens camera and shot several scenes in Leeds in October 1888 that are thought to represent the oldest surviving film footage in the world. It’s an intriguing story – not least because Le Prince’s sudden disappearance shortly before he was due to exhibit his invention gives it a mysterious and tragic romanticism worthy of cinema itself. Alas, while Wilkinson uncovers a wealth of evidence, his presenting style is a bit Alan Partridge and he just isn’t very good at making the story come alive on screen.

Still the Water (15)

Directed by: Naomi Kawase

Starring: Jun Yoshinaga, Nijirô Murakami

***

The discovery of a dead body floating in the sea provides a disturbing backdrop for Japanese director Naomi Kawase’s dreamy and surreal tale of first love and the encroaching complications of adulthood. Set on the Amami islands, the film revolves around Kaito (Nijirô Murakami), a sullen 16-year-old boy who lives with his hard-working single mother next door to the vivacious Kyoko (Jun Yoshinaga), whose own mother is battling a terrible illness. It is Kaito who discovers the dead body and while the experience disturbs him in ways he can’t process, it also brings him closer to Kyoko, who is trying to deal with the fact that her mother is nearing death. Kawase’s imagery is haunting but oblique, resulting in a film that’s beautiful to look at, but a tad baffling.

Minions (U)

Directed by: Kyle Balda, Pierre Coffin

Voices: Sandra Bullock, Jon Hamm, Pierre Coffin

***

Advertisement

Hide AdMuch-hyped, moderately entertaining spin-off from the hugely successful Despicable Me movies, Minions finds the titular pill-shaped yellow henchmen in 1960s London on the hunt for an evil master to serve. The film is at its best during the delightfully absurd prologue that sketches out the existential crises that repeatedly befall the Minions as they accidentally kill one detestable boss after another. Thenceforth it struggles to maintain a consistent gags-to-giggles ratio as a core group of Minions get involved with a female super-villain (voiced by Sandra Bullock) determined to steal the Crown Jewels. That said, it remains brightly coloured and fast-paced throughout and is also amusingly disrespectful of The Beatles songs its makers have presumably spent a fortune licensing for the soundtrack.