Martyn McLaughlin: Edinburgh's museums get millions, Glasgow's bawbees

When Elspeth King became curator of the People’s Palace in 1974, it did not take long for her to realise the scale of the challenge ahead. Composing a letter at her desk, she discovered the typewriter ribbon was so worn, only the red portion was usable. Black ink, it turned out, was an extravagance too far.

Such parsimony was dispiriting, if hardly surprising. The Glasgow museum’s recent exhibitions had received lukewarm reviews, and numerous exhibits were tarnished by misattributions. Undeterred, Dr King set about transforming its fortunes over the best part of two decades, scouring through a city on the cusp of a rebirth to salvage items which articulated its storied history.

Advertisement

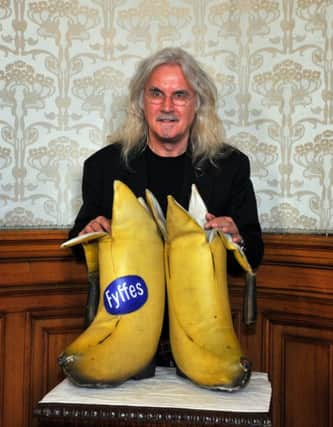

Hide AdThe artefacts were mostly of negligible value, but priceless to the people of Glasgow: the Big Yin’s banana boots pulled the punters in, but in the form of Shieldhall blancmange powders and tins of National Dried Milk, the collection preserved a living, breathing social history.

The public responded in kind. When Dr King took over, visitor numbers hovered around the 80,000 mark. By 1984, they soared above 202,000. Today, thanks in large part to her tenure, it is one of Britain’s great folk museums, frequented by more than 356,000 people last year.

It is little wonder the news that the museum and the adjoining Winter Gardens glasshouse are facing an imperilled future has met with such dismay. A structural engineering report has identified the need for at least £5m of work to make the glasshouse safe, and Glasgow City Council faces the daunting task of juggling its constrained budget while finding a way to relocate fire escapes so that the People’s Palace can remain open.

Following the tragedy at the Mack – the phoenix which succumbed to the flames – the realisation that another of Glasgow’s gems is under threat caps off an annus horribilis. It has been a year to remind us never to take the city’s rich cultural offerings for granted.

The People’s Palace is part of an extraordinary collection of museums that is the envy of nearly every city in western Europe, and the privilege of enjoying its treasures comes unburdened by admission charges. Yet as the council well knows, there is no such thing as a free museum.

Cumulatively, its museums draw more people than anywhere outside of London, with 3,928,297 visitors last year. One in every three trips to a museum or gallery in Scotland is recorded in Glasgow. Factor in the calibre of the art – with headlining works by Rembrandt, Monet, and van Gogh – and the collection is internationally important.

Advertisement

Hide AdPerversely, however, it’s bankrolled exclusively by the local authority to the tune of £12m a year. By contrast, the National Museums of Scotland, which is nationally funded, has a budget of £27.7m.

The custodians of Glasgow’s art have quietly raged against this status quo for decades. In 2001, 19 MSPs backed the city’s request for national funding, and positive talks were held with culture minister Sam Galbraith. Eight years later, Michael Russell held a summit to discuss a new national funding structure. “Nothing has changed in the museums sector for many years,” he said. It has changed little since.

Advertisement

Hide AdThe sole concession to Glasgow’s cause came in 2002 in the form of a one-off £3m payment towards the upkeep of the museums and the renovation of Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum. Other than that, the city has been fed scraps such as the Nationally Significant Collections accreditation scheme. For smaller museums, the initiative is a boon, with awards of up to £60,000 on offer, but such sums are bawbees compared to Glasgow’s needs.

The question of how to address them spans broader, complicated issues, such as how we structure and finance local government. So too must Glasgow address how previous refurbishments failed to identify such apparently longstanding issues with the Winter Gardens, and give serious consideration to how much – if any – control of its museums it is prepared to cede.

Finding a solution is made even more fraught by the long, bleak winter engulfing Scotland’s cultural landscape. The spike in funding for Creative Scotland announced in the last culture budget was welcome, but it obscured the conmtinuing diminution of central funds allocated to the national galleries, library, and museums. The tranche fell from £77m to £73.4m, the third successive year it has been scythed. Glasgow is fighting for a slice of an ever-shrinking pie.

Yet nourish it we must. This is not an academic argument. Glasgow’s museums budget has been pruned by £2m over the past decade, and it has wrestled with introducing admission charges and culling opening hours. At the turn of millennium, consideration was given to transferring the Burrell Collection to the care of the National Trust for Scotland. The ruinous financial forecast for local authorities means that such eventualities, and worse, cannot be dismissed.

A city yet to heal the wounds inflicted by Ian Lang’s decision to scrap plans for a National Gallery of Scottish Art can justifiably feel slighted, and as the soul searching over the future of the People’s Palace plays out, the debate will be framed as a struggle between Scotland’s two largest cities. Such reductive narratives must be resisted. This is not a parochial argument, but an artistic one. Glasgow’s desire to showcase its glittering jewels to the nation is undiminished. It is time to let it flourish.