Lost Edinburgh: The Porteous Riots

This article contains affiliate links. We may earn a small commission on items purchased through this article, but that does not affect our editorial judgement.

In January 1736, three men, Andrew Wilson, William Hall and George Robertson, were charged with smuggling and attempting to rob Collector of Excise, James Stark at the Pittenween Inn, Fife.

The three were then carted off in chains to Edinburgh’s notorious Tolbooth Prison to learn of their fate.

Smuggling in 18th century Scotland

Advertisement

Hide AdInstances of smuggling had risen dramatically since the Act of Union in 1707 which allowed hefty English taxes to be imposed equally upon goods in Scotland. The introduction of a malt tax in 1725 which led to a sharp increase in the price of ale was met with universal disapproval. Three decades on from its inception, a lingering hatred of the union persisted north of the border, and those bold enough to reject the law of the excisemen were often romanticised as genuine heroes of the people. Harsh sentences were placed on those who dared to commit such crimes. For the two of the three smugglers at Pittenween in 1736, this meant death.

Sentenced to hang

All three men were initially faced with the Grassmarket gallows, though William Hall had his sentence revoked for returning King’s Evidence against his fellow conspirators. Judgment day for Andrew Wilson and George Robertson was set for 14 April.

Just five days before they were due to be hanged, Wilson and Robertson attempted to escape the Tolbooth. Acting alongside a pair of horse thieves from the cell above them, they managed to saw through the bars of one of the Tolbooth’s narrow windows. Robertson squeezed through the gap and using rope, lowered himself to the High Street below. Wilson wasn’t too successful, his rather more portly frame preventing him from proceeding any further. When the guards arrived they were presented with the lower half of Andrew Wilson, lodged firmly in the window. The pair’s daring escape had been foiled.

Three days later the men were present at the Tolbooth Kirk for their pre-execution sermon – a customary practice for the condemned. During the service, the sprightly Robertson suddenly broke free and made a dash for the exit. He eventually fled to the Netherlands and spent the rest of his days running a tavern in Rotterdam. Andrew Wilson, however, was left to face his sentence.

Execution and riot

A large crowd gathered in Edinburgh’s Grassmarket on 14 April to witness the hanging of Andrew Wilson. The execution took place without incident, but the peace didn’t last long. Just as Wilson’s body was being cut down from the gallows, a section of the crowd began pelting the executioner with stones. Rumours had been rife that Wilson had been tortured while incarcerated and what had been a relatively calm sea of spectators quickly transformed into an angry mob. The City Guard, acting on the orders of the widely loathed (and allegedly intoxicated) Captain John Porteous, fired into the crowd in retaliation. Several lay dead as a result. Some soldiers decided to ignore the direct orders and fired into the air, resulting in the death of a young boy who had been watching the action unfold from his tenement window. A total of 9 were reported to have been killed and at least 20 wounded by the City Guard.

Porteous had served as Captain of Edinburgh’s City Guard since 1726. He was described as an arrogant and overbearing official with a keen sense of his own self importance. He was despised by the mob and the underclasses of Edinburgh society, and was now on trial for murder.

Porteous’ trial and lynching

Advertisement

Hide AdThere was no shortage of enthusiastic witnesses to testify against Porteous’ actions. The jury, no doubt spurred on by the mob gathered outside, did not hesitate in finding him guilty, and he was sentenced to hang on 8 September.

This was a rare outcome. Porteous was Captain of the City Guard and his actions, against what was a violent mob, were seen by some as absolutely necessary and justifiable. When the news reached London, Prime Minister, Sir Robert Walpole managed to secure Porteous a Royal Pardon. This would not go down well back in Scotland’s capital.

Advertisement

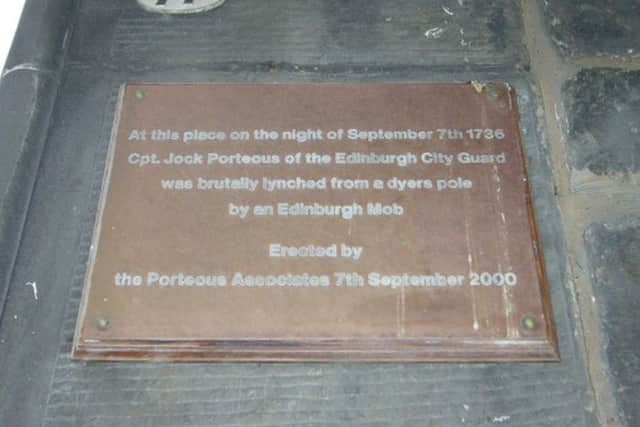

Hide AdOn the eve of Porteous’ proposed execution, a 4,000 strong mob took to the streets of Edinburgh. A total lockdown was ordered by the City Guard and all gates, including the Netherbow Port were closed – shutting out many troops stationed outside of the town. The enraged mob made their way to the Tolbooth Prison where Porteous was being held and set the jail door alight. Porteous attempted to flee but was eventually grabbed by force and dragged up the Lawnmarket, then down along the West Bow towards the Grassmarket where Andrew Wilson had met his end. Porteous was strung up on a dyer’s pole and brutally lynched until he ceased to move. The government would later declare a reward of £200 for any information of those responsible for Captain Porteous’ murder, but none of those guilty would ever be found.

Sir Walter Scott’s famous novel The Heart of Midlothian written in 1818 would later recall the events in great detail.

Today a plaque marks the spot on the Grassmarket where Porteous’ lynching took place.

• Visit Lost Edinburgh on their Facebook page, and follow them on Twitter @lostedinburgh