Lost Edinburgh: Picardie Village

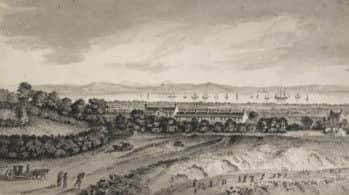

Back in the early 18th century there was no New Town. The concept was still decades away.

Edinburgh was an important city, but a small one, clinging on to its crag and tail, and hemmed in by its defensive walls. During this era, much of what we now term as districts of the city were made up of villages, hamlets and small clusters of housing very much separate from Edinburgh, albeit fairly well connected by roads.

Advertisement

Hide AdJust to the immediate north-west of Calton Hill, a new village was in the process of being created: Picardie Village.

History

The precise origins of how Picardie Village came into being have been hotly debated for at least two centuries. The most common story, which is portrayed as fact in the vast majority of publications describing the history of the area – and even on the window of the Conan Doyle pub on York Place – explains that the village was founded in 1730 for a group of Huguenot silk weavers escaping religious

persecution from their native region of Picardie following the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes. This version is fanciful for a number of reasons, not least because the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes was an event which took place at least 45 years before the village’s inception (meaning those French refugees would have been very old indeed). The source of this tale of events is uncertain, as is its accuracy.

The second, and most probable account, disputes the claim that the migrants were refugees. It simply asserts that they were enlisted for their skills in the weaving of cambric in the hope that the industry could flourish in Scotland. Whatever the case, a row of thirteen houses were built for the workers ‘by the city of Edinburgh on land feued by the city for the Governors of George Heriot’s

Hospital’. The row stood roughly on the spot of modern-day Picardy Place and was initially inhabited by ten families.

It is also written that the workers began a plantation of mulberry trees on the slopes of nearby Moultray’s Hill - later giving rise to the name of Multrees Walk between St Andrew Square and the St James Centre in 2003. However, the likelihood of the French migrants being responsible for this plantation is also shrouded in doubt.

Picardy Place

Advertisement

Hide AdThe houses of Picardie Village, or Little Picardy as it was later referred, stood until the early 1800s when the line of Queen Street was extended to link up with the head of Leith Walk. The village was eradicated, but its name would survive with the creation of Picardy Place.

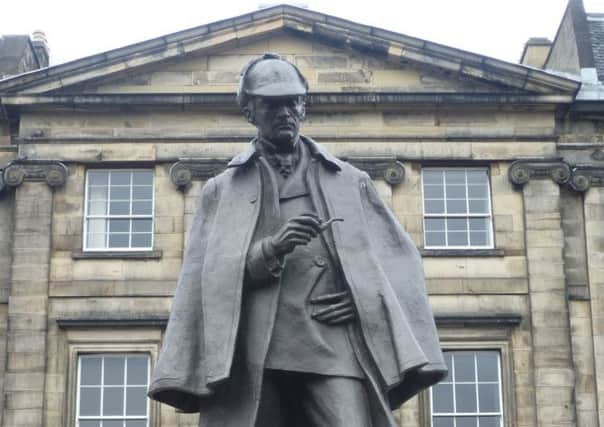

Conan Doyle

Picardy Place is most famous for its connection with one of the world’s most celebrated authors. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle was born in 1859 at Number 11. The popularity of Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes character endures to this day, but sadly his childhood home has long since bitten the dust.

Advertisement

Hide AdNumber 11 and the rest of the ‘Picardy triangle’ were swept away in 1969 as part of the (regrettable) comprehensive redevelopment of the St James and Greenside district. In 1973, an ill-advised kinetic light sculpture, which barely ever seemed to work, was erected on the new Picardy roundabout close to the former site of Sir Arthur Conan Doyles’ home.

Today the author is remembered in the name of the nearby pub, while a bronze statue of his greatest literary creation has stood on Picardy Place since 1991 - apart from a brief absence during the tram works.

Perhaps only Sherlock himself would be capable of separating embellished ‘fact’ from nonsensical fiction to unravel the complex mysteries surrounding the origins of the area.