Lost Edinburgh: The Act of Union

There was a time when the idea of a formal union between Scotland and England, two bitter foes who had clashed with one another for centuries, seemed unthinkable. It would take a complex series of events over the course of many years before Edinburgh was ready to relinquish its Parliament.

The Union’s roots were sown in 1503 when James IV of Scotland entered into marriage with Margaret Tudor, the eldest daughter of Henry VII of England. Their only child to survive into adulthood, the future James V, possessed both Stuart and Tudor blood.

Advertisement

Hide AdIn 1603 one of the most pivotal moments in the history of the British Isles arrived when James VI of Scotland was crowned James I of England following the death of the unmarried Elizabeth I. Upon his accession and relocation to London, he took the bold decision to name himself as King of Great Britain and Ireland and sought to implement a full political union between the countries. However, the idea was far from being popular with his English subjects and the radical attempt to unite the parliaments of Edinburgh and London would have to wait.

No political union as of yet then, but there would be a flag. The Flag of Great Britain, forerunner to the Union Flag, was first used in 1606 and featured St George’s Cross merged with the Cross of St Andrew. Throughout James VI and I’s proclamation which designated the new standard for use on ships, Scotland and England were referred to as North Britain and South Britain respectively - labels which would become very popular among many prominent unionists during the 18th and 19th centuries.

Cromwell’s union

In the fallout of the English Civil War and overthrow of the Stuart monarchy, Puritan military and political leader Oliver Cromwell conquered Scotland, and for the briefest of moments managed to establish the Commonwealth of England, Scotland and Ireland in 1653. Cromwell’s forced union was entirely dissolved in 1661 with the restoration of a Stuart king, Charles II, to the English throne.

Attempts to reinstate the union (which had been very popular with many Scottish MPs), in 1667 and 1689, ultimately came to nothing. As the 18th century dawned, however, the dire economic situation in Scotland began to make the possibility of merging with their vastly wealthier southern neighbours an attractive proposition - at least for its nobility.

Darien Scheme and move towards a union

Following the disastrous Darien Scheme (1698-1700) which attempted to establish a Scottish colony on the Isthmus of Panama, the country was almost bankrupt. At least one fifth of the nation’s wealth had been invested into the scheme which had been severely beset by failed crops, famine and disease. A siege by the Spanish in 1700 put paid to the venture once and for all. As a result, Scotland’s nobles were now extremely keen to pursue unification with England, to lift the country out of its sorry financial mess and perhaps recoup some of their hefty losses. A political union was also a favoured policy of Queen Anne, and by 1705 negotiations between the parliaments of England and Scotland had begun.

Treaty of Union and Edinburgh riots

There were benefits on either side which made a union desirable. For both countries there would be an increased freedom of trade, while England was also keen on ensuring that Scotland did not choose a different king from the one on the English throne. A union would prevent Scotland from forging new alliances, thereby quashing the threat of invasion. Among the various stipulations demanded by the Scottish elite, were that the country should maintain many of its core institutions, such as its legal system and Presbyterian faith.

Advertisement

Hide Ad

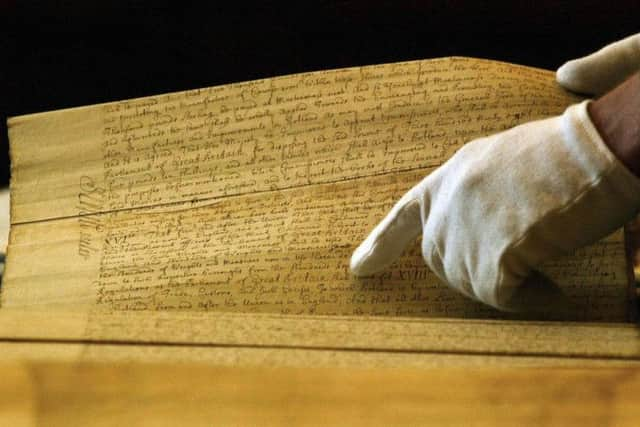

The Treaty of Union finally came into effect on 1 May 1707 after a year of negotiations and ratification by both goverments.

Explosive riots were a feature of daily life in the centre of the capital and in most other Scottish towns for the duration of the settlement. The sight of nationalist leader, the Duke of Hamilton, as he passed by carriage on the Royal Mile each day aroused passionate cheers from the throngs of Edinburgh locals. Meanwhile the leader of the unionist opposition, the Duke of Queensberry, required protection at all times as his consort was subjected to a volley of verbal insults and missiles ranging from rocks to manure. The Duke of Queensberry’s Canongate residence, Queensberry House, still stands today attached to the Scottish Parliament Building.

Advertisement

Hide AdWhen Robinson Crusoe author Daniel Defoe, a secret agent of the English government, arrived in Edinburgh in late 1706, he described the violent scene, ‘a Scots rabble is the worst of its kind’, while also stating, ‘for every Scot in favour of the union, there are 99 opposed’. The heated protests were of course in vain. The Act of Union was a deal between the ruling classes of Scotland and England, and the wishes of the overwhelming majority of the Scottish populace would be wholly ignored. The bells of St Giles rang out to the tune ‘Why should I be sad on my wedding day?’ Edinburgh, and indeed, all of Scotland, was in a state of mourning – the country had just lost its status as a self-governing independent nation.

19th century writer Robert Chalmers decried the period as Edinburgh’s ‘dark age’, stating that, ‘From the union, up to the middle of this century, the existence of the city seems to be in a perfect blank. No improvements of any sort marked the period. On the contrary; an air of gloom and depression pervaded the city; such as distinguished its history at no former period.’ A surprisingly negative summary when you consider that it was during this specific period that Edinburgh witnessed the creation of its magnificent New Town and some of its finest civic architecture, whilst also developing an enviable reputation as a hotbed of science, philosophy and creativity.

Accusations of bribery

Another twist in the tale of the Act of Union was the well-documented claim that members of the Scottish elite received bribes to sign the treaty – not from the English as is often mistakenly thought, but from their own compatriots. The claims of Robert Burns’ poem ‘Such a parcel of rogues in a nation’ that they were ‘bought and sold for English gold’ have always been a contentious piece of the story, but are not unfounded. Significant sums of money were paid to individuals who had incurred heavy losses from the Darien venture – many of whom were not even members of government.

Although not an immediate success (Edinburgh declared itself bankrupt in 1709 amid civil unrest), Scotland did eventually reap the benefits of its union with England. Despite an initial struggle with the higher levels of taxation, trade revenues increased by 2,500% between 1707 and the mid-1800s – three times as much as the increase experienced in England. As a part of the future British Empire, Scotland would go on to prosper like never before.

Independence referendum

At the time of writing the United Kingdom as we know it finds itself at a crossroads. Will Scotland choose to maintain its 307-year-old union or will it again become an independent nation? In just under three months’ time a democratic referendum will decide the outcome – something which was sorely lacking at Edinburgh in 1707.