John McKendrick: Darien colony failure has lessons for Russia stand-off

A bench outside the Maltings in quiet Salisbury was a strange place to reflect on a turning point in Scottish history. Reading the British papers on a rare trip back from the Caribbean, I was struck by the British press’ interest in our beleaguered Prime Minister’s and Foreign Secretary’s attempts to secure diplomatic support for action against the Putin regime. All of a sudden our ‘buccaneering Britain’, ‘open seas’, post-Brexit world has embraced the need for our European, and other, allies to hold our hands, to stand up to thugs from Moscow.

Understanding a wider world and the motivation of our friend and enemies, is, unsurprisingly, an essential aspect of worldly success.

Advertisement

Hide AdAs I researched the failure of the Scottish colonial venture of Darien in the steaming Panamanian jungle, the traditional explanation (blame the English) for this pivotal failure looked simplistic.

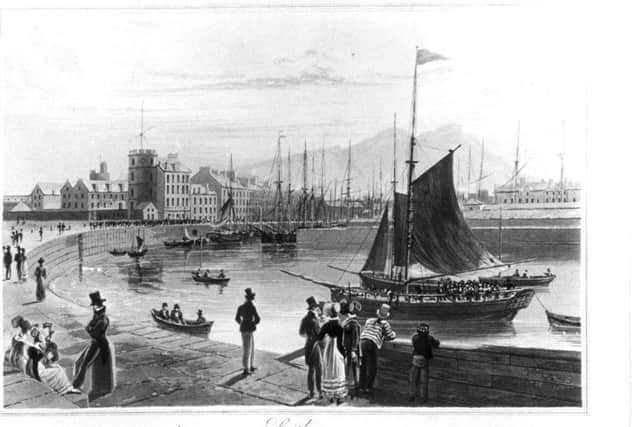

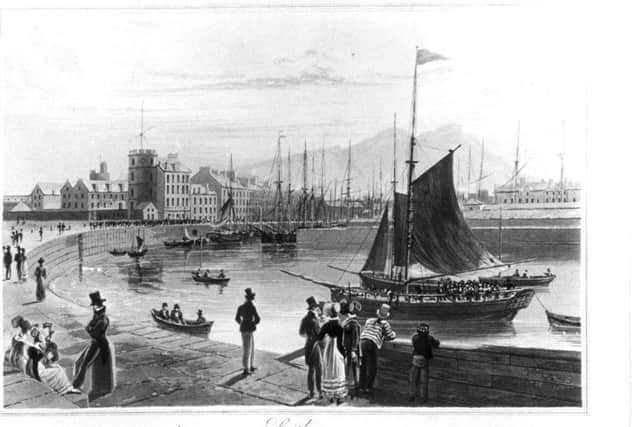

Most of us know a little about the Scottish attempt in the late 17th century to form a trading colony in modern-day Panama. William Paterson, that energetic founder of the Bank of England, promoted the “door of the seas and key of the

universe” – a fascinating idea to found a colony to trade goods from Europe to the Americas and onwards to Asia and back.

It could have been impoverished Scotland’s salvation, but as we know it was, in the moment, at least, a disaster, and led to the Act of Union. Received historical wisdom blames the English and King William in particular for Caledonia’s failure.

The reality is, unsurprisingly, more complex. Darien was not aided by the English (why would a rival nation help?) but most of the reasons for Caledonia’s tragic failure can be firmly placed at our own door.

Chief amongst them was our inept survey of late 17th century geopolitics and our lack of allies and diplomatic savviness. At that time, Europe and its possessions in the New World were complex places. Newcomers were required to tread with care. Nobody behind Caledonia worked that out to their own significant, personal cost.

Advertisement

Hide AdDarien, the ideal trading post, was not, as the un-worldly Scots assumed, unclaimed. In fact, it was very close to the most fundamental beating artery of the Spanish Empire: the Camino Real. This ‘pathway’ brought the huge volume of gold and silver from Spain’s American possessions from the Pacific to modern-day Panama City, and from there across the thin isthmus to the Caribbean, where this robbed wealth was sailed to Cadiz, to prop up the ailing Habsburg pretensions in

Europe.

New Edinburgh was placed too close to this vital artery. Caledonia could never be allowed to succeed. The Spanish King wrote to his New World commanders saying “to evict them [the Scots] is of the greatest importance to the Monarchy, for it concerns Our Holy Catholic Church, the preservation of Our Kingdom of Peru and Tierra Firma, the stability of the rest of the Indies, the riches and trade within them and not least the reputation and credit of our army and nation”.

Advertisement

Hide AdHe was serious and Spain would stop at nothing to remove the Scots. In the face of this powerful Hispanic mobilisation, the Jamaica Proclamation was neither here nor there. And, of course, while William was king of both England and Scotland, he was also a Dutchman. His foreign policy dictated protecting his homeland from Louis XIV of France. As the ailing Carlos II would soon die childless, William was desperate to stop Louis’ son taking the Spanish throne. William was therefore engaged in a considerable diplomatic battle in Europe and part of this was also played out in the New World.

William could not be seen to support the Company of Scotland, jeopardising his careful diplomatic overtures towards Spain. The Caledonians appreciated very little of this. Without proper allies, their cause was sunk.

So, whilst contemporary Caledonians were happy to place the blame for the collapse of Darien on the English, the real fault lay with their own assessment of geopolitics and the complex world of European alliances. In fact, communications from one Spanish general to another in January 1700, singled out English Admiral Benbow for protecting the Scots from the mighty Spanish Windward fleet. So much then for the Proclamation: a gesture for a Hispanic audience.

Benbow was the admired admiral who battled pirates and, depending upon the political context, the French or the Spanish armadas in the Caribbean. The Spanish military correspondence, which was found in the Panamanian archives, makes clear Benbow used his formidable fleet to protect the Caledonians from a Spanish incursion. Curious then that no contemporary account of the engagements makes mention of such crucial English assistance. In fact, this important role by the English navy has been lost for more than 300 years. The Caledonians needed a bogeyman to help explain away their own failure, who better to blame than their close neighbours?

Benbow lies buried in a cool church in Kingston, Jamaica, cut down aged 52 by the French. He was not the first Englishman to look out for the Scots abroad.

Going it alone in after the UK’s departure from the European Union will require a firm understanding of how and where Britain can push ahead. Buccaneers were pirates who harassed the Spanish main from their Caribbean hideouts – hardly a fitting description for post-Brexit Britain. Our need for alliances and friendship has been brought dramatically into focus this week.

And the Caledonians’ fate demonstrates the dangers of blindly going out alone.

John McKendrick is a QC and the author of Darien: A Journey In Search of Empire. He currently lives in the Caribbean.