Jean-Claude Floc’h on his Edinburgh illustrations

JEAN-Claude Floc’h cuts a dash. Tall and elegant, with smoothly-coiffured hair, dressed in a blue blazer, soft grey flannel trousers and bi-coloured shoes, he’s quite the dandy, and could have stepped right off the page of a Louis Vuitton travel book. Which is exactly what he did.

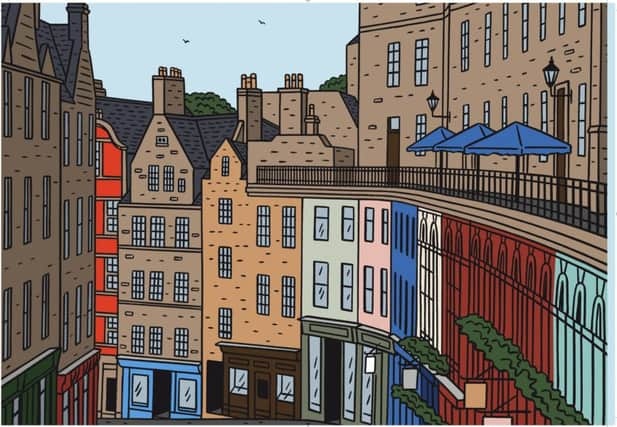

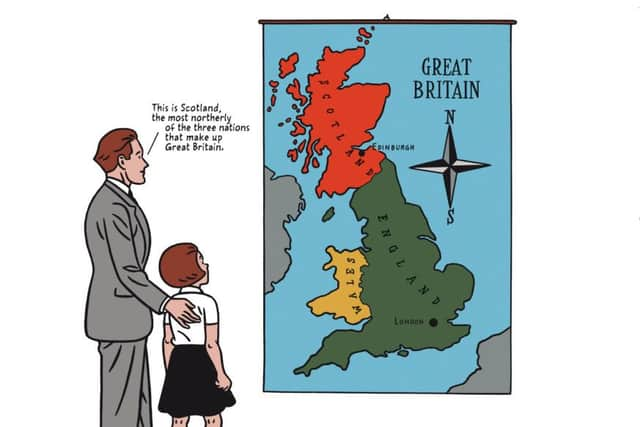

The French illustrator, comic artist and writer features himself in many of the 130 drawings he created for the book on Edinburgh, the Lothians and Fife that the luxury French design house commissioned him to write and illustrate. It is one of a series of travel books that includes titles dedicated to the Arctic, Easter Island, London, New York, Paris and Vietnam. Works of art in themselves, the volumes are a celebration of the fashion brand’s roots as creators of elegant luggage for the well-travelled and well-heeled.

Advertisement

Hide AdPart sketch book and part travel journal, they depict destinations through the eyes of artists. Graphic novelist Lorenzo Mattotti has captured Vietnam, manga master Jirô Taniguchi depicted Venice and now Floc’h has worked his magic on Edinburgh, a city he has visited many times.

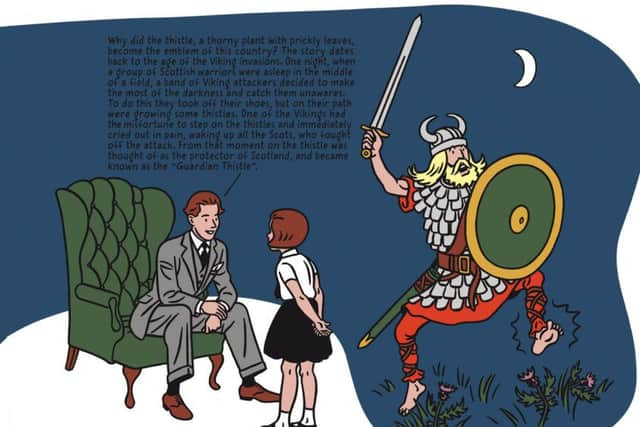

A disciple of Hergé, creator of Tintin, Floc’h is an exponent of the “ligne claire” style of drawing inspired by the Belgian tradition of comic illustration, with a nod to the pop artists Lichtenstein and Warhol. There is a very simplified background, no hatching, and each element in the illustration is equally important. His creations include book jackets, film posters, title sequences for filmmakers Woody Allen, Mike Leigh and Alain Resnais, children’s collections, and advertising and illustrations for magazines and newspapers, including The New Yorker and Le Monde.

In town to launch the book, he has been agonising over his wardrobe because of the changeable Scottish weather.

“It was 40 degrees in Paris and 13 here so it was hard to choose, but I did my best,” he says in his accented English. “I would call what I’m wearing today Bing Crosby, because he was always like that with a blazer and flannel trousers. People say I’m always elegant, but I say I’m just me. I have a tailor and I buy clothes if I see something, but being 62, I have everything. Sometimes I buy a tie, although I have 200 already. I have kilts because my first wife had Scottish family, but it’s too hot, so… flannel. Designed for the cold summer. Perfect.” Floc’h is the perfect choice to create a travel book that will sit on the shelves of Colette and Galignani in Paris, the Conran Shop in London and Vuitton stores, including the one in Edinburgh’s Multrees Walk. Firstly, appearance is important to him: he is as punctilious about his drawing as he is about his dress. Details matter.

Secondly, he has a love of all things British, from Agatha Christie and Alfred Hitchcock, to Stevenson and Sir Walter Scott. He has a particular love of Scotland and with an illustrator’s eye has addressed our symbols and traditions, from thistles to tartan, from Edinburgh’s memorial benches to his favourite hole on his favourite golf course: the 13th at North Berwick, which he says “with the view of the Bass Rock in the distance, is the stuff dreams are made of. It’s special.”

Using the device in the book of taking his daughter on a journey through the history of Scotland, from the Viking invasions to the present day, it’s a very personal selection of the things that matter to Floc’h.

Advertisement

Hide Ad“Everything I write is true. The little girl is my daughter, the man is me. I hate people with imagination. I believe in reality – as long as you make it a little bit different.”

Floc’h’s attention to detail is apparent from the minute we meet. I have a copy of the book in my hand and he immediately dispatches someone to his room to ask his wife Marion for a “special pen to write on this special paper”.

Advertisement

Hide Ad“There is a mistake,” he explains. “On this page here, it should be 1830 and it says 1930 so I will put some black in to make it an eight.”

I admire the invisible repair and enquire whether he will be doing this with every copy?

“I would have liked! But it’s impossible,” he says, regretfully. “Oh yes, it’s in my genes, in my bones. I could not do otherwise.”

Floc’h’s father was a printer and Jean-Claude grew up in an environment where getting it right mattered. He may also have his father to thank for his love of Tintin.

“It was really funny that we had Tintin in the house, because my father was not a funny guy. He was an artist but he had his first son at 18 and five children in four years, because I have twin sisters, so he had to go to his father’s printing factory and work all his life. He said to me, ‘One day I will paint again,’ but he never did. But my brother once won a competition by making a magazine and the prize was a year’s supply of Tintin. I think my father was reading them in secret, and when the year was over, he ordered more, but never said.

“What Hergé was doing with Tintin, that was innocent. But my generation discovered Lichtenstein and Andy Warhol and innocence was dead for good. And for bad. For good, because we were not naive anymore, and for bad, because it can be good to be naive.”

Advertisement

Hide AdFor the French, cartoons are a serious matter, never more so than after the Charlie Hebdo killings earlier this year. Does Floc’h think what happened changed the way he sees things?

“No, no, it’s a terrible question you ask me,” he says. “Because I have a daughter who is drawing, but she is 19 and did nothing, and her stupid grandfather sent a message saying, ‘I admire you because you make dangerous work.’ I just hate that.

Advertisement

Hide Ad“One of the people who died, the two old ones, the great drawers, [Jean] Cabut and [Georges] Wolinski, I knew Wolinski and he was really great, a free guy. But some of the guys at Charlie Hebdo were young and a little bit stupid. I met one guy that was a friend of Wolinski who saw him just two days before that killing, and you know what Wolinski said to him? ‘Charb is crazy, he is doing too much. He will make us die, make us be killed.’ And it happened you see? Of course, if you want to speak about freedom, I would be on your side, but life is so much more complicated.”

Then he sings a lyric from the Beatles’ The End, from the Abbey Road album: “And in the end the love you take is equal to the love you make.”

“This is exactly my point of view. They made an awful thing but curiously they created something stronger than the awful thing they did. They created something more beautiful because even cowardly people reacted and got alive again and had something to say about it. That’s good, definitely. People today just think about talking in their stupid cellphones, so suddenly they need something strong like that to wake them up. But I think maybe they are sleeping again.”

Floc’h has always been certain of his own judgment and confident in his powers of discrimination, whether they fly in the face of conventional wisdom or not.

“I don’t like what everyone is supposed to love. I always go in the other direction. Maybe they think I’m a little bit snobbish but if being snobbish is to be different and make my own road, I’m very snobbish.

“When I was young I knew what I wanted. If I can say this about myself, I had taste. I would not say good taste, but I would say taste. To know if it is salt or pepper, to be able to tell the difference. Good and bad exist, whatever that stupid singer Michael Jackson says.”

Advertisement

Hide AdSo sure is Floc’h of his own judgment that he very nearly didn’t accept the commission for the Louis Vuitton book.

“I said to them, being 60 I have no vocation to being a tourist guide, goodbye. When I went home, my wife said, ‘Oh, you are stupid because you love Edinburgh and you have many things to say about Scotland and Scottish people.’ So I called them back and said I’d do it, but on the condition I wrote as well as drew.”

Advertisement

Hide Ad“You have to be brave,” he says. “I have had a beautiful life, but you have to be brave. Painting with a brush is like a martial art. You have to be in full possession of your mind and body. When someone is asking for a drawing and saying, oh maybe you can change something, no I can’t. Except – I’m not stupid – if the guy gives me a good idea I say with pleasure, thank you for the idea. But most of the time they ask because they are cowards themselves and I say no.”

Born in 1953 in Mayenne, western France, Floc’h went to the School of Decorative Arts in Paris and began his career drawing illustrations for books and the press. He attracted attention with his first collection of comics in 1977, Le Rendez-vous de Sevenoaks, published in collaboration with François Riviere, and together they created the series known as Une Triologie Anglaise (An English Trilogy), influenced by Christie and Hitchcock. The Blitz books followed, and Une vie de reve: Fragments d’une autobiographie ideale (Fragments of an ideal autobiography), in which Floc’h imagines his autobiography, in which he lives a long life from 360 BC to 4 May, 2046 and fulfils his fantasies. He studies with Plato and Epicure, is the translator between Charles de Gaulle and Winston Churchill and is in the studio with François Boucher as he paints the mistress of Louis Quinze, The Resting Maiden, “a beautiful young lady with such an ass”. On his 60th birthday in 2013 his entire oeuvre was celebrated in Inventaire.

Floc’h dates his love of all things on this side of the Channel back to his realisation at the age of ten that the British number plate was a thing of beauty compared with the aesthetic affront that adorned French cars.

“It was so beautiful, like poetry for me. And the French ones were beginning with numbers and it was just awful. I hated that. I was ashamed of the French plates and I was ashamed of being French. It was the same with the flag. And the windows. I hate French windows and love yours. You could multiply this with everything. I love London, Edinburgh, I don’t like Paris.”

As for his current surroundings of the Balmoral hotel, where Floc’h stayed for three weeks while walking around Edinburgh and travelling to St Andrews and North Berwick, researching the book, he rather misses the decor of 20 years ago when the tartan carpet and stag engraving reigned.

“People want to see that when they come to Scotland. Tartan, tweed, you should be proud of your culture. Maybe you noticed, maybe you will think I am harsh, but I didn’t draw any contemporary Scottish people in my book. Maybe it’s hard… there’s nobody nicer than Scottish people, but they are…” he hesitates, searching for a diplomatic way to put it... “It’s quite hard to look at them because they are…”

Advertisement

Hide AdWe both look down from the hotel on to North Bridge which is filled with rushing pedestrians, the flotsam and jetsam of the tides of humanity that wash through a busy metropolis.

“I think about Joan Collins saying that when she was a young girl when she wanted to see the fat lady and the tattooed man they had to go to the circus. Obviously people here don’t try to be elegant,” he says.

Advertisement

Hide AdPerhaps we’re more practical, I suggest, than the well-turned out French. “But I complain about them too!” he says. “When they speak about the elegant young Parisienne I say where are they? But if you go for 15 days to Germany then come back to Paris, you say, ‘oh, I see what you mean’. So the Scots should be the most elegant and original people to look at. Look what Vivienne Westwood did with the tartan and that marvellous use of the kilt. When I see the Scots in Paris for the Six Nations, they are all in kilts and they look just great. I don’t ask people to be like me,” he says, gesturing down his flannelled leg to his two-tone shoes.

So, no people in the pictures then?

“No, humanity is represented by me. And the little girl is my daughter Sacha, now grown up into a boring 19-year-old, but when she was younger, this was how I made an education for her. It’s an elegant idea to use the little girl, because maybe people would not like it if I was talking directly to them in this way about Scotland, and a quality of life. There is only one question, where is the quality?”

The book is dedicated to his wife Marion, to whom he says he owes the colour scheme and his joie de vivre. It was also Marion who accompanied him and took photographs from which he later did the illustrations.

“She is the woman of my life. I was 53 already when I met her, she’s 12 years younger and she had two daughters, but I knew. And because it works for her too, she said to me, ‘Now the quest for the other is finished.’

“She did the colour on the computer, and it was the first time we had done it like this because of the number of illustrations. For this I chose 12 or 15 colours and we always used those, not always trying to get it close to reality. Reality, I don’t even know what it is. It’s better like that, because I would become crazy if I know.”

Does he see things differently? Does he automatically, condense and simplify when he looks at what he is going to draw.

Advertisement

Hide Ad“The point is that you are clarity. It’s not a clarity you create because you are drawing, it’s a clarity you have over yourself. Louis Vuitton are publishing a second book at the same time as mine, by Blaise Drummond about the Arctic. The drawings are simple, the Arctic, a rock, ice, and his son said, ‘But father, you didn’t draw the grass’. And he said, ‘Of course, because I don’t give a damn with the grass!’ That’s what I do. I put the humanity in, the daughter and me, and a few people you see like Raeburn, Ramsay, Scott, Hume, Connery.”

Next up for Floc’h is a book about books, a tribute to the writers Floc’h admires, with writing on one side of the page and an illustration on the other. There will be text from André Breton, the letters of Calamity Jane, and RL Stevenson.

Advertisement

Hide Ad“It’s a pleasure for me. I have never thought I worked. Everything is in front of me to discover. I was a happy person before and I’m more happy now, because it’s so easy. I made 40 books, but it’s not like I was asking to do a book every year. I never work, never. I don’t get the point. I do exactly what I want. If I want to read, I read, if I want to go and walk, I walk, and when I write and draw, it’s because at that moment it’s the really best thing that I want to do. Believe me, it works.”

Twitter: @JanetChristie2

• Edinburgh, The Lothians And Fife by Floc’h is published by Louis Vuitton, hardback, £38; available from Louis Vuitton, Multrees Walk, Edinburgh, Conran Shop, London, and online at louisvuitton.com