Insight: Civil rights 50 years after Martin Luther King

US lawyer James Wilson was still a child when he sat near an open field in the heart of the Alabama Black Belt and watched an effigy burn on a fiery cross. “The Ku Klux Klan used to meet by the river down from our house in Montgomery,” he says in a gravelly southern drawl. “My grandfather must have thought it was important for us to see because he put my brother and me in the car and took us down there. Some things are burned on your mind forever and that is one of them.”

Wilson’s grandfather was Solomon S Seay Sr: minister, prime mover in the Montgomery bus boycott and mentor to the young Martin Luther King, who called him “the spiritual father” of the civil rights movement. With his mother studying medicine in the north, Wilson lived with Seay and witnessed much of the violence and the protests of the mid-60s. Now 62, he remembers the blood on his grandfather’s shirt after he was shot on his porch by white supremacists; he remembers the National Guards posted outside their house to protect them; and he remembers joining the Selma to Montgomery marchers as they made their way to the Capitol Building to hear King deliver his famous “How Long? Not Long” speech.

Advertisement

Hide Ad“How long will justice be crucified and truth bear it?” King asked the 25,000-strong crowd. “How long? Not long, because the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice.”

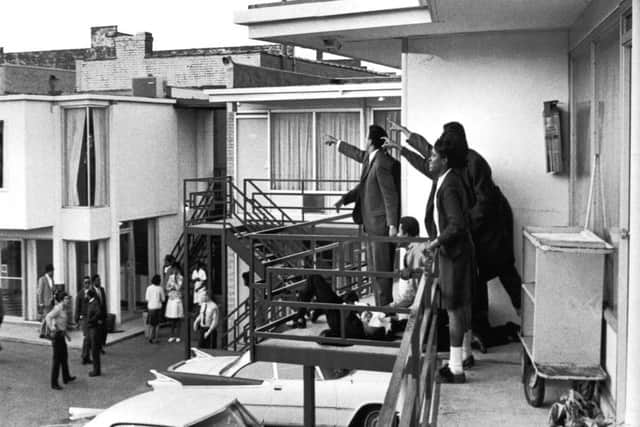

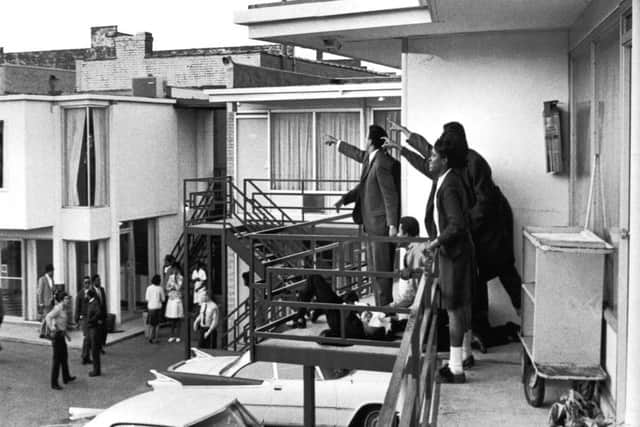

Like millions of others, Wilson also remembers the bulletin – 50 years ago on Wednesday – which broke the news that King had been assassinated as he stood on the balcony of his room on the second floor of the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee.

By then, King had moved on; with the black franchise secured through the Voting Rights Act 1965, he was waging war against poverty (which he saw as the root of all conflict) and the Vietnam War: causes that brought him a fresh crop of enemies.

He had come to Memphis to support a sanitation workers’ strike and was preparing for another march on Washington to lobby congress on behalf of the dispossessed.

While the US was shocked to its core by the killing of John F Kennedy, King’s was much anticipated, even by him. “We were always afraid he was going to get killed,” says Wilson. “There had been attempts on his life before, so even though we weren’t expecting it to happen [right] then, we knew the threat was real.”

All the same, the single shot fired on 4 April, 1968, reverberated across the globe. In Edinburgh, it made Jamaican immigrant Geoff Palmer – now Sir Geoff Palmer and Professor Emeritus at Heriot-Watt University – realise the road towards equality might be more twisted than King had predicted. “If someone who was speaking on your behalf could be killed, you knew change and justice were still a long way off,” he says.

Advertisement

Hide AdFor others, the reaction was one of fear. “We saw Dr King as being a force against violence; we knew his death was going to unleash a huge amount of very righteous and pent-up fury,” says Vickie Batzka, who was born in a small predominantly white town in Tennessee, but now lives in Lexington, Kentucky.

In the days that followed, there were riots in 125 US cities, turned into tinderboxes by segregation, workplace discrimination, police brutality and poverty. Washington, Chicago and Baltimore were among the worst affected, with lives lost and thousands of properties burned and looted.

Advertisement

Hide AdMuch has happened since King’s assassination. There have been black governors and (a handful of) black Supreme Court judges; 2008 saw the election of President Barack Obama – a hugely significant moment for a country built on slavery. Yet, the past decade has also seen the rise of the right and a resurgence in racial violence: police shootings of unarmed black men, the murder of nine black worshippers in a church in Charleston, South Carolina, and the mowing down of a white student who supported the removal of a statue to Confederate leader Robert E Lee in Charlottesville, Virginia. Politically too, there has been backsliding: gerrymandering is rife, voting rights have been eroded and some say there are attempts to undermine the public education system.

Out of such injustices, a new movement, Black Lives Matter, has been born; last week, activists were protesting against the shooting of unarmed 22-year-old Stephon Clark in his grandmother’s backyard. As leaders urged those involved to remain peaceful, it was impossible not to think of King making the same plea the day before his death and to wonder: How much has changed? Almost half a century after he proclaimed “I’ve been to the mountaintop”, are underprivileged African Americans any closer to the promised land?

At his home in North Queensferry, retired Church of Scotland minister Rev Dr Iain Whyte, a prominent Scottish civil rights campaigner, is sorting through photographs of the weeks he spent in a seminary in Atlanta in 1964.

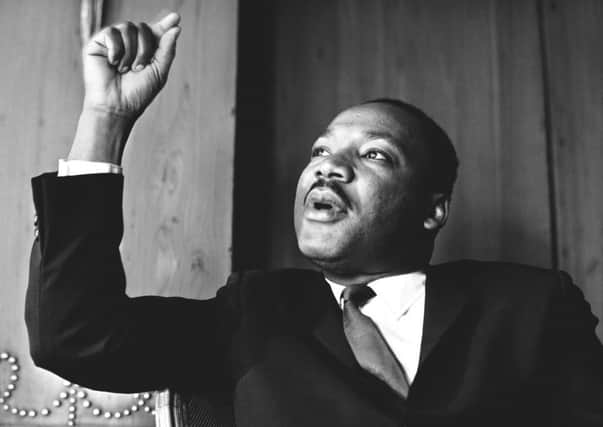

The highlight of his trip was a visit to the offices of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference where he spent half an hour with King. “He was smaller than I expected, but you saw the quality of the man when he started talking,” Whyte recalls. King asked Whyte to tell the people of Scotland about the struggle. But he also sent him on a mission: to spend a night with white human rights activists Clifford and Virginia Durr, who were feeling increasingly isolated in their Montgomery home.

While in the south, Whyte spent time working with the programme to register black voters in Mississippi, also known as Freedom Summer. Many thought his actions foolhardy. On the first day of the initiative, three volunteers – James Chaney, Andrew Goodman and Mickey Schwerner – had gone missing; their bodies were recovered a few days later. But Whyte ignored the warnings. He spent two weeks with Albert Peters, a 94-year-old African American in Greenville, where he registered voters, gave talks at one of the freedom schools and learned to eat grits. “I asked Albert one evening: ‘Are you not frightened having me here?’ because a lot of houses were being firebombed,” says Whyte. “He replied: ‘Lord, no , they can’t do anything to me now: I am 94, I am going to heaven soon.’”

After the summer, Whyte went home to Scotland, but two years later, he received a Scots Fellowship to study at Union Theological Seminary in New York; there he shared a room with Vickie Batzka’s husband David. David had spent the whole of Freedom Summer on the volunteer programme in Clarksdale, Mississippi, but by 1966/67, he and Whyte were more involved in protests against the Vietnam War.

Advertisement

Hide AdSadly, David died in 2002, but his family has continued his quest for social justice; Vickie’s older daughter, Candice and her grandson Gareth have taken part in Black Lives Matter protests; her younger daughter Diana is married to an African American.

Vickie Batzka says she is lucky to live in Lexington. A patch of blue in a mostly red state, Lexington has an openly gay mayor and quietly removed its Confederate statues without the threatened backlash. But she has watched what is happening to her country with mounting consternation. “My family was moderate Republican. I grew up in a Republican house, but the Republican Party today would not recognise Ronald Reagan as a member of their party because he was far more liberal than they ever intend to be,” she says.

Advertisement

Hide Ad“The scariest thing about what’s going on is that our view of what is decent and moral is shifting so far to the right. The new normal is what scares me. The new normal is really, really bad.”

One of the issues that concerns Batzka is the way some states are reintroducing tough and potentially discriminatory ID requirements for voter registration. These moves were made possible by a Supreme Court ruling which overturned a provision of the Voting Rights Act 1965. This provision required states with a history of racial discrimination to seek approval from the Federal Authorities in Washington for any changes to the electoral rules.

“It is mostly happening in states where there is a Republican governor, a Republican house and a Republican senate,” Batzka says. “They are purging voters lists by saying ‘we sent them a letter and they didn’t respond so we took them off’ or by removing those who haven’t voted in two successive elections. In some states, the only way for people who don’t have a driver’s licence or a gun permit to get the required ID is to travel to an office out of town.”

Equally distressing are police shootings of unarmed black men in places such as Ferguson, Missouri; Tulsa, Oklahoma; Baton Rouge, Louisiana; Falcon Heights, Minnesota and now Sacramento, California, many of which result in no charges or the acquittals of those involved.

“I don’t think all police are bad, but I do think some have become prejudiced about the danger to themselves so they use their gun before they do anything else,” says Batzka. “To me, that’s what Black Lives Matter is talking about: that we have to stop seeing black as dangerous and deadly; that we have to start seeing African Americans as human beings.”

In the summer of 1964, David and the other volunteers were given a list of Dos and Don’ts to reduce the risk of trouble. These included don’t speed, don’t jaywalk, don’t talk back – in other words, don’t do anything that might bring you to the attention of white police officers. Returning for the 30th anniversary in 1994, he was pleased to find many of the officers on duty were black. “David could see progress,” says Batzka. “But I think if he were able to go back now, he would wonder what had happened. Because we are no longer moving forward.”

Advertisement

Hide AdFive hundred miles away in Montgomery, James Wilson is also trapped in civil rights Groundhog Day, fighting the same old battles; trying to shore up the gains made by King and Seay. Right now, he is campaigning against the use of public money to fund charter schools, a move he says was prompted by black residents taking control of some public school boards.

Although there are those who argue charter schools will improve outcomes for black pupils, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is concerned it will drain resources from the public school system. “Around 90 per cent of the black kids in this town are in public schools and if you take the money from the public schools to fund charter schools – which are really private – you leave the public schools under-resourced and we are back where we started.”

Advertisement

Hide AdArguably, the Obama presidency – while symbolically important – further polarised America while doing little to narrow the economic gap. “I did have hope when Obama was president, but what we saw was a systematic effort to destroy everything he tried to do, partly because they perceived no black man should ever have held that office,” says Wilson.

Having seen the advances in the 60s, is Wilson shocked by the rise of white supremacists under Trump? “Laws are passed to control the conduct of people and for a period of time those laws helped to quieten down some of the racial tensions,” he says. “But you know, it’s difficult to change the hearts of people. When you get demagogues like Trump, they appeal to latent passions. He has given the racists a forum. They feel comfortable saying things they would once have buried.”

In 2015, Whyte went back to Alabama to take part in a 50th anniversary march from Selma to Montgomery; there, he met up with Batzka and Wilson: three people from very different backgrounds, all dedicated to racial equality.

At a memorial service at Brown Chapel African Methodist Episcopal Church, King’s son, Martin Luther King III, railed against the renewed attack on voting rights. With Obama a lame duck nearing the end of his second term, his speech seemed less upbeat than the one given by his father in 1965 (despite the violence meted out to the protesters).

Three years on, the gloom has not lifted; though Batzka is part of an ecumenical movement which works to build more cohesive communities, she fears a return of the frustration that fuelled the riots of 1968. “I think if we continue to see the current treatment of immigrants, if we continue to see the majority of income going to a small group of people, and the have-nots, and the not-gonna-haves and the never-going-to-get-out-of-it groups getting larger, the fury will come back,” she says.

For his part, Wilson fears young civil rights activists are not ready for the battle that lies ahead. “When we were fighting back in 40s, 50s, 60s we knew we didn’t have rights,” he says. “But now we’ve generations of blacks who have been lulled into believing that they did.

Advertisement

Hide Ad“Black Lives Matter has come about because it’s a shock for them to discover discriminatory policies exist and to see people shot down in hi-tech lynchings – but they don’t have any foundation of the struggle. The movement has no direction. What they need to do is to resurrect some of the civil rights folks and get some purpose to their campaigning.”

If King were alive today, he would be 89. No doubt, he would still be speaking out: against racial hatred, against poverty, against Trump. The depressing thing is so many of his best-known lines would be as powerful and as pertinent as they were when he first uttered them.

Advertisement

Hide Ad“How long will prejudice blind the visions of men, darken their understanding and drive bright-eyed wisdom from her sacred throne?

“How long will justice be crucified and truth bear it?”

How long? Too long.