Influence of Paul Klee is incalculable, his imagery an inspiration

He had a frightened presentiment, just a vague sense of the right course. But when a picture was fixed and still, he saw that he had come the true way, he was happy. Klee too set out to discover a new land.”

Klee died in Switzerland in 1940. This tribute is from an obituary by Jankel Adler. His description of Klee as a kind of Columbus of 20th-century painting is very apt. Klee sailed the seas of 20th century art. He was close to some of its key figures and learnt from them, but nevertheless he found an extensive, imaginative territory that was entirely his own. Each picture seems like a new discovery.

Advertisement

Hide AdBoth Klee and Adler fled the Nazis, Klee to his native Switzerland, but Adler to Glasgow. The presence in Scotland of someone who knew Klee is a reminder that even during the war, the reputation of one of the most remarkable German artists of the 20th century was kept alive here.

Klee’s work had been seen in Scotland before the war and was shown at the SSA in 1934. The painter John Maxwell organised this show and its impact on his own painting as well as that of his close friend William Gillies was immediate. Indeed with Maxwell it was enduring. Klee sold at least one work from this show, too. Threatening Snowstorm was bought by RK Blair, Honorary Vice-President of the SSA, and is now in the National collection. It is a beautiful and very characteristic picture and looks good in the big retrospective now showing at Tate Modern.

Klee studied art in Munich. A friend of Kandinsky and a member of the Blaue Reiter group, he already had some success before the war, but after the war his reputation developed quickly on the Continent and in America, but less in the UK. Indeed the SSA show is the more remarkable as public exhibitions (as opposed to dealer shows) have been infrequent. Klee has been neglected. This comprehensive show rights a historic wrong.

A critical moment in Klee’s career was a visit to Paris in 1912. One of the earliest works here, When God Considered the Creation of the Plants, in pale pinks and greys and painted in 1913, is inspired directly by the new art of Cubism. Nevertheless it already has Klee’s distinctive touch. Even quite abstract, intersecting “cubist” shapes are never just dumbly there. They are always invested with the artist’s own imaginative presence as distinctive as handwriting. If he makes a grid as he often does, it always slopes and so, like handwriting, his art balances formal discipline with the idiosyncrasies of personality.

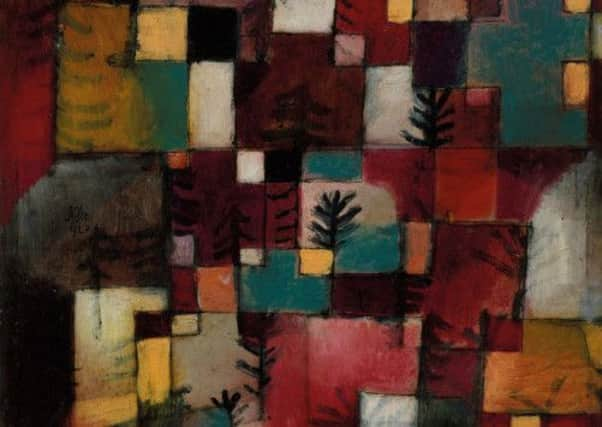

Cubism was a liberation, but so were the Delaunays’ paintings of pure, independent colour. That was where Klee’s art really took off. Colour is pure poetry in his hands. But the progress of his art was never linear. He got hold of an idea, often a purely technical one, like layering watercolour in regular patterns to create mysterious depths of light and dark, or painting in a kind of mosaic of dots in a technique that united Byzantine art with pointillism to extraordinary imaginative effect, then he worked his way through it. The exhibition follows these patterns of creation, grouping works together in separate spaces against a broader chronological flow and so seeming to follow his inspiration.

His pictures are small, but their impact and influence is in inverse proportion to their size. In his very last years, back in Switzerland and against the background of war, however, he painted several bigger pictures like Forest Witches, or Rich Harbour which also have a kind of dramatic grandeur. Perhaps they reflected contemporary events. They certainly influenced post-war abstract painting in both Germany and America.

Advertisement

Hide AdKlee served in the war, but benefited from an undeclared policy that kept artists away from the front line. Then, in 1921, he joined the Bauhaus where he taught for ten years, moving with it from Weimar to Dessau, before leaving to teach at Dusseldorf, where he met Jankel Adler. The Bauhaus was a dynamo of new thinking and Klee was at the heart of it.

Always systematic, he prepared his teaching very carefully and his Pedagogical Notebooks, the published outlines of his courses, have been a bible for art students ever since, or at least they were as long as students learnt to paint. This means his influence is incalculable, reaching far beyond his undoubted impact on major artists as diverse as Miró and Bridget Riley to penetrate deeply into the experience of countless art students for several generations. Indeed the curator of this show, Edinburgh graduate Matthew Gale, told me that was where his own love of Klee began.

Advertisement

Hide AdHe was systematic in his teaching and numbered his pictures systematically too, but his art is never systematic. It is more like magic. He is a shaman crossing from this world to another, imaginative one and taking us with him. He loved music and played the violin and there is a musical analogy in it too. It is there in his subtle graduations of tone and line and in the unique, spiky drawing line that dances across the coloured grounds he laid like a solo instrument against the orchestra. This distinctive style of drawing was the product of his method of tracing drawings into paintings using paper and black oil paint. It has been much imitated since (consider Ralph Steadman, for instance).

His imagery moves seamlessly in and out of abstraction, conjuring figures and animate shapes from apparently inanimate forms. A single curve suggesting a dome is enough to conjure a whole city out of nothing more than blocks of colour. Rectangles become fields and forests by the addition of one or two spiky trees. You can speak of narrative in such pictures and his titles invite it, but it is always elusive, a memory drifting at the edge of consciousness. The way abstract shapes take on meaning is a kind of metamorphosis, a releasing of spirits previously locked in the forms.

Klee is like a shaman and so I found myself quite unexpectedly thinking of him in the British Museum’s remarkable exhibition, Beyond El Dorado. From relatively small communities in Colombia, this art is much more sympathetic and approachable than the more familiar, but alien-seeming art of the Central and South American empires. It is shaped by shamanistic ideas about spiritual transformation and metamorphosis. There are amazing masks and representations of people, and birds, bats and crocodiles. Klee, too, manages to be at once childlike and profound and the formal language here seems to chime with his, as though at a certain level of imaginative intensity images have some kind of communal likeness. What is most remarkable, however, is that the principal artistic medium of these beautiful objects is gold. But innocent of any commercial value, it was prized simply for its beauty and its brilliance which emulates the sun. It was commercial greed, of course, which drove the Conquistadors to destroy these civilisations. They sought the golden city of El Dorado, but El Dorado was not a city at all. It was a man adorned with gold in the rituals of the Muesca people on Lake Guatavita. In their greed the Spanish tried to move a mountain to drain the lake to reach the gold thrown into it. They failed of course.

The British Museum opened this exhibition the same day as that monster of modern art, Frieze, opened its doors. The cheapest ticket is £32, £50 for Frieze and Frieze Masters. Contemporary art is on the side of the Conquistadors, it seems, not that of Klee and the shamans of Colombia. • Paul Klee: Making Visible is at Tate Modern, London, until 9 March; Beyond El Dorado is at the British Museum, London, until 23 March. Frieze London ended yesterday