Film reviews: Wild Tales | Cinderella | Get Hard

FILM OF THE WEEK

Wild Tales (15)

Directed by Damián Szifrón Starring: Ricardo Darín, Leonardo Sbaraglia, Oscar Martínez

****

The portmanteau film is a tricky one to get right. Collecting together a bunch of short films on a related theme, the end results are usually only memorable because of a few diamonds in the rough, not because the film as a whole is a gleaming jewel. Sometimes that’s down to the disparate styles and talents of different directors having a kryptonite effect on each other (see New York Stories, the Tarantino-led Four Rooms, or the V/H/S horror franchise); sometimes it’s down to a single filmmaker being unable to consistently and entertainingly follow through on an idea (Jim Jarmusch’s Coffee & Cigarettes springs to mind); sometimes it’s simply because the idea itself is misconceived (see the overstuffed Paris, je t’aime).

Advertisement

Hide AdThe Argentine box-office smash Wild Tales has a few of those issues: a couple of its six stories lose a modicum of momentum and there’s a tonal switch in one – built around a hit-and-run accident – that feels out of place (even if it does have an amusing sting in the tale). But for the most part, writer/director Damián Szifrón’s Oscar-nominated anthology of blackly comic vignettes about our viciously primal nature succeeds not only by being outrageously entertaining, but by functioning as a sort of hellish magic mirror, one that reflects our hidden nature back at us to better illustrate the ways in which civilised society is predicated on a fundamental denial of our basest instincts.

Things get off to a flying start with Pasternak, a deliciously depraved, aeroplane-set revenge story in which a flirty conversation between a model and a classical music critic soon reveals a mutual acquaintance whose presence in each of their lives is more troubling and sinister than this apparent coincidence at first implies. Like a short, sharp horror riff on the gaudy, camp grotesquerie of producer Pedro Almodóvar’s own sky-bound satire I’m So Excited!, this prologue – with its railing-against-petty-injustice, all-consequences-be-damned conclusion – does a fine and hilarious job of setting the tone for what follows.

Little Bomb, for instance, starring Ricardo Darín, gradually builds an explosive story around an engineer’s inability to prevent maddening bureaucracy from ruining his life after a dispute over a parking violation with a city official leads him down a violent path.

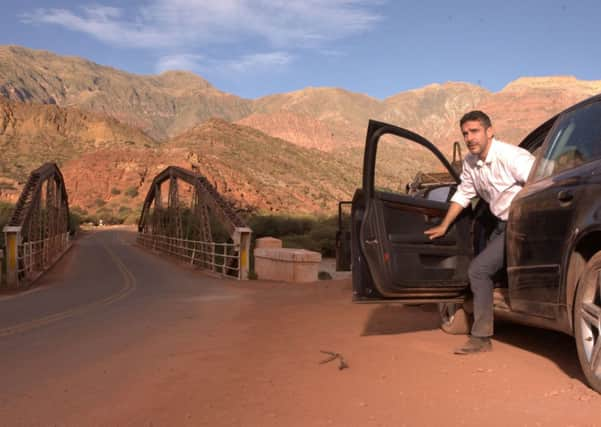

In The Strongest One, meanwhile, a road-rage incident escalates in macabre, class-fuelled fashion as an Audi driver elicits the disdain of a thuggish truck driver. Resulting at first in a Duel-style game of vehicular intimidation on a twisty and deserted stretch of country road, the ensuing conflict soon takes on an uber-macho quality that sends both drivers over the edge, as bound together by their meat-headed obdurateness as they are by the seat belts that literally entangle them in a precarious, life-threatening position.

In some respects what Szifrón is doing here is dramatising and commenting on the daily outrage perpetrated on social media by unthinking fools determined to let the slightest issue offend them in ways that are thoroughly disproportionate to their lives. In some of the stories, such as The Rats (in which a waitress decides to take revenge on a local Mafioso for driving her father to suicide) or The Proposal (in which a wealthy businessman tries to buy his son out of trouble after a traffic accident), the characters’ actions result in collateral damage that exposes the utter derangement of the situation, irrespective of how justified their initial actions might at first have seemed. In others stories, such as the aforementioned Little Bomb, the positive public responses to stupid acts of violence reveal the extent to which many people want to live vicariously through those irrational enough to loose themselves from the shackles of civilised society.

But there’s a distinct funhouse quality to all these distorted reflections on real life too. They’re entertaining to watch precisely because each elaborately constructed scenario reveals how frequently we’re our own worst enemy. Nothing in the film does this better, or with more verve, than its final chapter, the unhinged Till Death Do Us Part. Thrusting us into the midst of a wedding going disastrously wrong, the film zeroes in on a bride who discovers her new husband’s infidelity with one of his colleagues just moments before their first dance. With the offending party also a guest, what follows is a spectacularly violent and cathartic loss of control in which the bride’s reversion to her most atavistic self clears her mind enough to exact a punishment on her husband that makes the conclusion to Gone Girl seem mild. But it also underscores how institutions designed to buttress social norms can be exploited to punish those who deviate from them – providing, of course, you’re prepared to go down with them.

Cinderella (U)

Directed by: Kenneth Branagh

Advertisement

Hide AdStarring: Lily James, Cate Blanchett, Richard Madden, Helena Bonham Carter

***

Have courage, and be kind.” That’s the credo by which the eponymous heroine of Disney’s latest live-action update of one of its classic animated fairytales lives her life. It could, however, just as easily serve as a mantra for Kenneth Branagh’s take on the film, which he’s directed from a script by Chris Weitz. Not only is their adaptation courageous enough to treat what people love about the story – both the animated musical version and the Charles Perrault-penned fairytale on which it’s based – with enough respect to eschew the easy option of modernising it with a hip and radical make-over, it’s kind enough to the characters to get round the problematic sexual politics of the story without making a big statement about them.

Advertisement

Hide AdIn this version, Cinderella (played by Lily James, inset) unwittingly meets her prince (Richard Madden) long before the ball and the romance that follows depends less on being bowled over by the bells and whistles of royalty and magically enhanced haute couture than it does on the mutual connection that fuses two people’s souls together but in no way guarantees everything is going to be easy for them. It’s refreshingly devoid of off-the-peg signifiers of psychological darkness too. Unlike Maleficent, this isn’t a film about a misunderstood villain. As the wicked stepmother to Ella (the ash-inspired prefix comes later in the film), Cate Blanchett doesn’t overwhelm proceedings or steal the movie from its heroine. Her cruelty towards her stepdaughter may have been born of frustration at having lost her true love much earlier in her life, but even though the film has empathy for her and her ditzy daughters (entertainingly played by Holliday Grainger and Sophie McShera), it keeps the focus on the unbreakable Ella. Her goodness is her strength; it’s not some boring quality that needs to be swept under the carpet just because we live in a cynical, irony-drenched age where sincerity is easily mocked.

Which isn’t to say the film is without fault. Because so much of it is played straight, the film, at times, misses the utter delight Amy Adams brought to the Disney princess archetype in the playfully subversive Enchanted (though pretty much anyone is going to struggle to fill the shoes of an actress as luminous as Adams). The plot, meanwhile, at times feels a little disjointed thanks to our over-familiarity with it. But Branagh and his team make up for this with a gorgeously designed, brightly coloured and richly detailed fairytale universe, one that benefits from opulent physical sets over blanket CGI designs. It’s a welcome throwback to old-school movie-making, something that kids weaned on Frozen (and there’s a new Frozen animated short film playing before Cinderella so get there early) may even find themselves loving.

NEW RELEASES

The Spongebob Movie: Sponge Out of Water (U)

Directed by: Paul Tibbitt

Voices: Antonio Banderas, Tom Kenny, Mr Lawrence, Matt Berry

***

“Knock it off, you’re making the movie too long,” says a character of a rapping dolphin (voiced by Matt Berry) near the end of this belated big screen return for the late 1990s/early 2000s kiddie pop-culture phenomenon. Had that gag happened at the 60-minute mark it would have been funny, but after 90 minutes of random stuff happening on screen it feels more like a guilty admission by the filmmakers that the hour’s worth of plot they did have has been wrung thoroughly dry. That’s a shame because the speed, frivolous nature and sheer preponderance of the slapstick gags during the early, fully animated sequences are joyously anarchic, revolving as they do around SpongeBob (voiced by Tom Kenny) teaming up with his deviously diminutive enemy, Plankton (Mr Lawrence), in order to rescue the underwater town of Bikini Bottom from a fast-food-shortage-inspired descent into mayhem. But as a plot twist brings SpongeBob and his pals into the real world – via a frame story involving a pirate street-food vendor (played by Antonio Banderas) – the film descends into charmless CGI overload, not helped by bandwagon-jumping the superhero trend without even using the opportunity to send it up.

Get Hard (15)

Directed by: Etan Cohen

Starring: Will Ferrell, Kevin Hart, Craig T Nelson

*

Casual racism, casual misogyny and blatant homophobia combine in this horribly conceived buddy movie about a billionaire financier who hires someone he thinks is an ex-con just because he’s black to teach him how to survive prison following his indictment for fraud. Will Ferrell stars as the aforementioned white-collar criminal – an impossibly naïve wolf of Wall Street whose fear of being put in a passive sexual position leads him to enlist the services of Kevin Hart’s car-wash entrepreneur, little realising his newfound friend’s knowledge of thug life actually comes from multiple viewings of Boyz n the Hood. With pretty much every gag built around the characters’ collective fear of sodomy and their distaste for any and all forms of homosexual activity, the film is offensive on many levels, even before you factor in the ironic (but not really) racial banter between Ferrell and Hart – or the sleazy objectification of some of its (minor) female characters.

The Face of An Angel (15)

Directed by: Michael Winterbottom

Starring: Daniel Brühl, Kate Beckinsale, Valerio Mastandrea, Cara Delevingne

**

Advertisement

Hide AdInspired by the Amanda Knox trial and the sensationalist media coverage surrounding it, Michael Winterbottom’s latest experimental effort fictionalises the case, then tries to comment on the impossibility of finding an objective truth by casting Daniel Brühl as a filmmaker hanging around Sienna, Italy trying to figure out how to make a film about it. It’s an interesting idea in theory, just not in execution, particularly as Brühl’s character descends into a coke-fuelled paranoid haze while also attempting to sniffily transcend the true-crime genre by incorporating Dante’s The Devine Comedy into his script. Unlike Winterbottom’s previous fourth-wall-breaking movies and TV series about the thin line between notoriety and celebrity (A Cock and Bull Story, 24 Hour Party People, the two seasons of the sublime TV show The Trip), the depiction of the creative process here is far too tedious and pretentious to illuminate anything meaningful about the way fiction and reality intersect.

FOLLOW US

SCOTSMAN TABLET AND MOBILE APPS