Interview: director James Gray and actor Charlie Hunnam on heading deep into the Amazon to shoot The Lost City of Z

In 1925, a British explorer by the name of Colonel Percival Fawcett disappeared in the Amazon never to be seen again. At the time he was searching for a lost civilization he’d become convinced was hidden deep in the jungle, a place he referred to as Z. Unlike the mythical El Dorado that had so preoccupied the conquistadors, Fawcett’s expedition was not born out of a desire to find cities of gold, but to find conclusive proof that the indigenous peoples of Amazonia were as advanced and sophisticated in their social development as their British and European counterparts.

His disappearance, however, overshadowed his objectives. He became a legend, inspiring numerous expeditions in the decades that followed as glory hunters became obsessed with solving the mystery of his vanishing. Given that Fawcett was also friend of King Solomon’s Mines author H Rider Haggard and an inspiration for Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (he used Fawcett’s field reports to help write The Lost World), his story inevitably sounds like perfect cinematic fodder. But in 2017, the kind of movie adventures his exploits might once have inspired would be highly questionable. If history has taught us anything it’s that colonialism wasn’t some grand consequence-free adventure and even presenting a modern spin on the type of Conradian quest that Apocalypse Now attempted risks falling back on certain ethnographic stereotypes.

Advertisement

Hide Ad“The idea of a white man in the jungle is a very tricky, dangerous subject matter,” agrees James Gray, whose new movie The Lost City of Z tells Fawcett’s story. “I viewed this not as a challenge but as a way of hitting the racism head on and making it the text of the movie rather than the subtext.”

Starring Charlie Hunnam as Fawcett, Sienna Miller as his proto-feminist wife Nina and Robert Pattinson as his expedition companion Henry Costin, the film presents Fawcett as a man driven at first by a desire to fight against his own lack of social mobility (his father had been a drunk who’d destroyed the family name). Nevertheless, his increasingly enlightened view of the indigenous tribes of the Americas reflects his hardening attitude against society’s determination to rank and compartmentalise everyone. That’s certainly how Hunnam saw it.

“His desire to escape what he saw as the very oppressive and marginalising social climate that he was born into was fascinating” confirms the Newcastle-born actor, best known these days for his seven-season run as the lead in hit US cable show Sons of Anarchy. “But I think it goes beyond that. I think it’s relevant to anybody living in the world where they have a sense of being oppressed and this horrible tendency we have of prioritising one person’s need over another, whether that’s based on economic standing or race or creed or sexuality or gender.”

The Lost City of Z, which is based on the historical component of New Yorker writer David Grann’s best-selling book of the same name, shouldn’t be mistaken for a “white saviour” movie, though. It might not look at the issue from an indigenous point of view, as last year’s Embrace of the Serpent did, but Fawcett definitely has his flaws. He’s not fully formed in his thinking, and Gray, who’s own films – such as We Own the Night and Two Lovers – have thus far all been set in New York, reckons there’s still value in telling this type of story from the white, western perspective. “Do you really think we don’t need any more stories about the white man’s racism in the developing world? I think we do.”

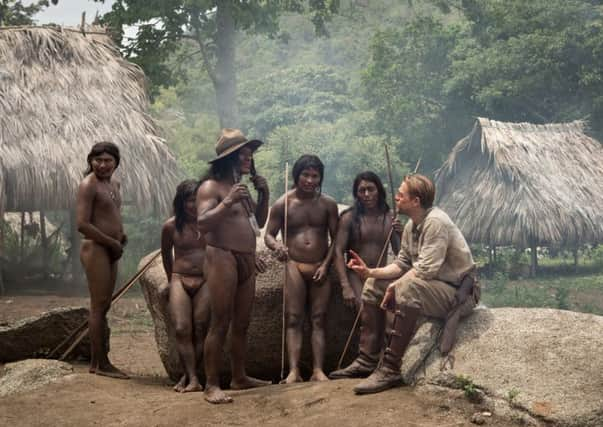

In this respect he felt it essential to shoot the film in Colombia rather than in places where filmmaking infrastructure already exists, such as Australia or South Africa. Working with four different indigenous tribes on the film, part of being culturally sensitive was, he says, to respect their independence and disinterest in what he describes as the “white man’s view of them”.

“If I could present the indigenous people as not needing us in any way,” he elaborates, “I thought that would be a way to conquer the stereotype. It’s up to the viewer to decide if I pulled it off. They were independent actors in their own story. They didn’t need us to validate them.”

Advertisement

Hide AdThe filmmakers were the invaders in other words – and in more ways than one. “I realised we are the temporary invaders of a word that is conquered by insects,” laughs Gray of shooting in jungles with temperatures of 100 degrees Fahrenheit and 100 percent humidity. “It was physically punishing.”

It was tough for Hunnam too. He was a last-minute replacement for Benedict Cumberbatch, who pulled out shortly before production was due to start when his wife became pregnant. Even then, Gray, who’d only ever seen Hunnam in Sons of Anarchy, refused to consider him. “I only wanted to cast someone who was British,” recalls the director, sheepishly. “Then the producer said to me: ‘You’re an idiot. He’s from Newcastle.’”

Advertisement

Hide Ad“I’ll take that as a compliment,” says Hunnam, who at the time was in the midst of shooting Guy Ritchie’s forthcoming King Arthur: Legend of the Sword (“It’s like Lord of the Rings meets Snatch,” he says). Though he only had ten days between films to properly prepare, it was, he says, too good an opportunity to pass up. Partly this was because Fawcett’s determination to make something of himself resonated with his own tunnel-visioned determination to escape the limitations of his own upbringing in economically deprived areas of Newcastle and the Lake District. But also he just wanted to make a film in this manner. “That definitely was part of the appeal,” he says. “The current environment of filmmaking is very spectacle based. So just the idea that we would go back to a classic idea of character and shoot on film and explore the environment as it is… there was just an ethos to the way James wanted to make this film that felt like a substantial return to, for want of a better description, the way films should be made.” n

The Lost City of Z is in cinemas from Friday