Aidan Smith's TV week: Brian Cox: How the Other Half Live (C5), Imagine ... Douglas Stuart (BBC1), 1899 (Netflix)

In BBC1’s Imagine … author Douglas Stuart returns to Glasgow and the site of his flattened high-rise to remember how the city was “discarded” by Thatcherism. “We felt like we were the collateral damage of some distant government’s plan to develop a country which just didn’t bring us along and into the future,” he says. “It was that feeling which ebbed away hope, which brought in addiction.” Stuart’s mother died of alcoholism when he was 16. Up until then he’d been her carer. All of this hardship and heartache fed into Shuggie Bain, his astonishing Booker-winning debut novel.

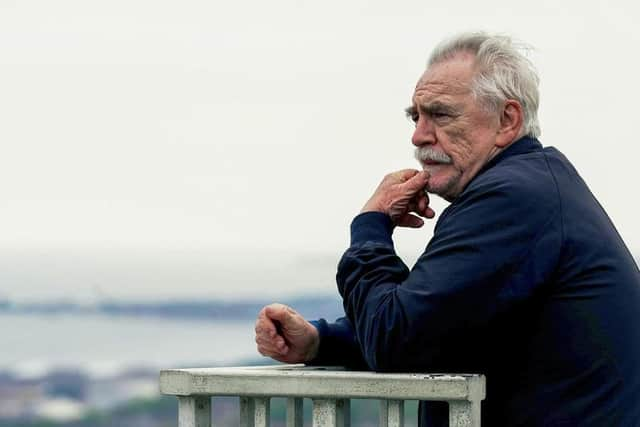

If Stuart is angry about the hand dealt his young life and his city - and he is - then in the documentary he doesn’t show it. He talks like a church minister - calm, measured, serene. If you want anger then watch Brian Cox: How the Other Half Live (Channel 5).

Advertisement

Hide AdI love this guy and it’s nothing to do with a bag of sweets. Okay, partly it is. Half a century ago Cox was our most promising young actor, standing atop Dundee Law as the subject of a BBC Scotland profile being produced by my father, and I was a bored kid who’d decided that location filming really wasn’t glamorous at all. Until he handed me the sweets.

Of course I also love him for Succession and Logan Roy, the billionaire media mogul he calls his “evil twin” who has no issues with money, the more of it the better. Cox though has lots of issues. Money for him is “a cloud, the demon, my Damocles sword”. That’s what happens when your father dies when you’re six, leaving the family with just ten quid in the bank book - “destitute”.

In this documentary he’s investigating why the world has become so divided between the haves and have nots. The anger comes when, back in Dundee, he’s handed a pinny to help out at the Lochee Community Larder. If you’ve used up all your allotted visits to the food banks and don’t mind just-out-of-date produce gifted by supermarkets, you end up here. Cox listens to the struggles of two of the staff who can’t make ends meet as cleaners. “So I come here on Fridays so I can feed my son at weekends,” said one.

Cox wants to end the doc right there. “If you have any sensibility at all this is pitiful - f****n’ pitiful. I feel like a mercenary.” It’s powerful, emotional stuff. We learn that during the Covid, when the billionaires couldn’t go on holiday, they amused themselves by buying - no, devouring - property. Thus, the ten richest people on the planet were able to more than double their money, making them wealthier than the three billion poorest people in the world put together.

Cox in Miami meets an estate agent selling a quayside mansion for $27 million - fully-furnished, presumably because prospective buyers are too lazy to kit it out themselves or have poor taste. The agent will take a three percent cut and last year in total would have earned $17 million. But not far away a poorer district is being redeveloped for more homes for the rich, so its occupants are being turfed out. America, says Cox, is “happy to use these people as servants and maids but not to care for them. It’s f****d, well and truly f****d”.

He’s reduced to tears a few times, despairing over how the privations of his childhood in Dundee have returned to haunt the place. In truth, I thought this section was going to be an even harder watch, having read an interview with Cox about how at the Lochee Community Larder an emaciated man with a stick and a sign on his arm told him: “I collect food for folk who can’t get here, who have children problems or they’re old. If I don’t do it, nobody will.” Cox then asked about the sign. The man replied: “I’m blind.” This encounter hasn’t made the cut although there’s a second part to come. Britain’s 15th richest person, gold leaf on his walls, tells Cox he’d be in favour of a wealth tax but only with worldwide agreement and that’s nigh-on impossible. “Well, we have to look after each other,” insists Cox. “That’s what society’s about.”

Advertisement

Hide AdStuart speaks movingly about his own privations. His mum would have nightmares about affording even a pair of shoes for him, so when he went to have a successful career in fashion, the exclusivity of the clothes bothered him: “I couldn’t care for things that were really, really expensive and only for the few.” Unfortunately, though, his interviewer, Alan Yentob, is an awkward, distracting presence. Is his wearing of braces in Glasgow an attempt to blend in with the artisans? Is he worried one of them will jump out and ping them?

I’ll tell you what we’ve been missing: more ocean-going thrills and laughs, even if the latter are unintentional. The Poseidon Adventure was the long-time gold standard here and now, in the wake of the passing of Angela Lansbury, comes 1899 (Netflix), highfalutin hokum from Germany about a transatlantic liner which encounters another ship which disappeared four months before. “The sea knows when death is nearby,” pronounces someone. I know when enjoyable ludicrousness is nearby.

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.