Six myths about the Edinburgh Festivals debunked

#1: Edinburgh was the natural choice for a post-war arts festival

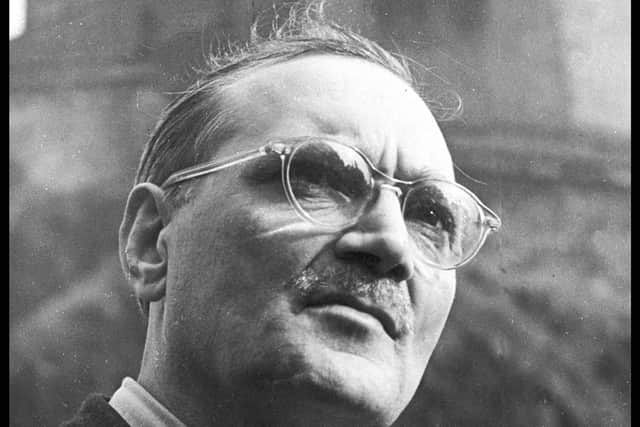

When Rudolf Bing, a Jewish emigre who had fled Austria in the 1930s and gone on to become general manager at Glyndebourne, had an idea for a new UK Festival of Music and Drama in 1943, his first choice was Oxford. When this fell through, into the frame stepped Henry Harvey Wood, then working with the British Council in Edinburgh.

Advertisement

Hide AdWhile the city matched Bing’s criteria – great scenery and just about enough theatres to host the programme – it took a bit of imagination to see the dour, blustery Athens of the North as a festival destination. However, Bing reasoned, with the festivals of mainland Europe wrecked by war, the time was ripe. After meeting with him in London in 1944, Wood set out to gain the backing of the local movers and shakers, from Lady Rosebery and the Lord Provost to Scotsman editor James Murray Watson.

The Edinburgh International Festival began with a special service at St Giles Cathedral on Sunday 24 August, 1947. The next day, the Scotsman carried a picture, alongside stories of Sikh rebellion in Punjab and the cabinet’s latest austerity measures. Having been an advocate for the festival from the beginning, the paper now reported daily on its progress: fine weather, an information kiosk in Princes Street Gardens fielding thousands of queries, the Festival Club in the Assembly Rooms buzzing with “a gay and cosmopolitan crowd”.

Meanwhile, the critics, far from phased by the arrival of the Hallé Orchestra, Sadlers Wells Ballet and Alec Guinness in their city, got on with the business of critiquing. While Glyndebourne’s production of Le Nozze di Figaro was acclaimed as “the finest experience of the week”, the theatre critic ventured that The Taming of the Shrew (presented by the Old Vic) was “not [the] best introduction to the world’s greatest dramatist”.

The critics also reviewed the eight companies who showed up without an invitation (the Fringe did not yet even have a name), praising the Christine Orr Players’ production of Macbeth in the YMCA hall for its “intensity and excitement”. By the end of the week, the paper reported that “Edinburgh has surprised even some of her citizens”. She had acquired a festival spirit.

#2: The Fringe was the fastest growing of the festivals

While it’s now taken for granted that the gargantuan proportions of the Fringe far exceed those of the International Festival, its growth in the early years was incremental. In 1947, it was another festival which was poised to make a quantum leap.

The Edinburgh International Festival of Documentary Film also launched in 1947, running for a week. A year later it was back with a three-week programme featuring 100 films from 25 countries, including Rossellini’s Germany, Year Zero and the premier of Robert Flaherty’s Louisiana Story. Stephen Ackroyd, writing in Documentary Film News, described packed houses and a “care-free carnival atmosphere.”

Advertisement

Hide AdThe Film Festival also learned early the power of a good review. When Scotsman art critic RH Westwater enthused about Henri Storck’s Rubens, queues formed round the block. The only solution was to keep screening the 64-minute movie back to back in the small cinema in Hill street until the crowds were satisfied.

In 1949, the festival hosted the UK premier of Jour de Fete with Jacques Tati (the audience laughed so much one observer wondered if the structure of the building was at risk), and the 10th anniversary was attended by the Queen, Prince Philip and Princess Margaret.

Advertisement

Hide AdThe Film Festival quickly established a reputation for serious movie know-how, gradually broadening its portfolio to take in more than just documentaries. Retrospectives of work by directors such as Ingmar Berman, John Huston and Werner Herzog helped cement its reputation and, in 1972, the festival – well ahead of its time – hosted a showcase by women directors.

But while the Film Festival was managing to compete with its bigger rivals in Berlin and Cannes, it was doing so on a shoestring. Financial difficulties in 1971 necessitated a bail-out by Edinburgh Corporation and the Scottish Film Council, and its future hung in the balance, not for the last time. It’s a reminder that Edinburgh’s Festivals, despite their success, are a fragile ecosystem the resilience of which can’t be taken for granted.

#3: Beyond the Fringe was an early Fringe highlight

In 1960, four relative unknowns took Edinburgh by storm with a revue called Beyond the Fringe: Peter Cook, Dudley Moore, Jonathan Miller and Alan Bennett. While it is often cited as an early example of the Fringe’s propensity for launching careers, this show was actually part of the International Festival, programmed by director Robert Ponsonby to cock a snook at the Fringe.

It was a huge success. The Scotsman critic (signing off only as “D.L.”) described it as “a performance of such deft, sophisticated and topical wit that it justified an international festival just to see it”.

Rudolph Bing had been right: it was just the right time for a new arts festival, and the Edinburgh International Festival quickly established itself as able to attract the best performers in the world: the New York and Vienna Philharmonics, Herbert von Karajan, Yehudi Menuhin, Margot Fonteyn, Maria Callas, Teatro Libero.

At this point, the Fringe was still finding its feet. There was no Fringe programme until 1955, and no central organisation. The Festival Fringe Society was set up in 1959, creating a brochure and box office, but it took until 1963 for Edinburgh University to decide the Fringe needed a dedicated phone line to take the pressure off its operators. The first administrator, John Milligan, was appointed in 1971, at which point the programme still fitted on two sides of A4 paper.

Advertisement

Hide AdThe Fringe couldn’t compete with the International Festival on big budget productions like opera and orchestral recitals, but it could in drama, often seen as a weak point at EIF because its directors tended to be music buffs. As early as 1959, playwright Hugh Ross Williamson, writing in the Scotsman, proclaimed that “nobody in their right mind would go to the official festival”, its drama programme was so dull.

It was during the tenure of Alastair Moffat as Fringe administrator (1976-81) that the festival moved forward in leaps and bounds.

Advertisement

Hide AdPromoting the Fringe, enabling sponsorship deals and streamlining organisation, he doubled the number of companies appearing to just under 500 in five years. By the time he stood down, the Fringe was the biggest arts festival in the world.

#4: The Fringe has always been the place to get discovered

By this time, something else had happened to reinvigorate the Fringe. At the 1972 Fringe Society AGM, discussion turned to the issue of new work: there wasn’t enough of it. Every company on the Fringe took a financial risk, but a re-run of a well-known play was less risky at the box office than a new piece by an unknown.

A solution was proposed by The Scotsman’s arts editor, Allen Wright, in the form of the Fringe First Awards, which were launched the following year. Voted on by a panel of Scotsman critics, the awards recognised excellence in new writing, whether from an internationally acclaimed company or a group of students with their first show.

Over the years, Fringe Firsts were awarded to people who would become household names: Rowan Atkinson, John Godber, Sam Shephard. They would help launch the careers of playwrights such as David Greig, Gregory Burke and Jo Clifford, and companies like Riot Group, The TEAM and Ontroerend Goet.

While a Fringe First can change a show’s fortunes overnight, even a positive review can make a big difference. Realising the importance of reviews, Wright significantly increased the Scotsman’s Fringe coverage. This continued to grow, as the Fringe did, until, in the mid 1990s, the Scotsman began to publish a 20-page festival supplement every day, reviewing hundreds of Fringe shows per year alongside work in the other festivals. That commitment continues today.

The Fringe Firsts had an almost immediate impact. A total of 45 new plays in 1972 increased to 138 in 1977. The Traverse Theatre, set up in 1963 and a strong participant on the Fringe ever since, has become a year-round home for new writing. All this has helped establish the Fringe as the place where emerging writers, directors, performers and comedians can make their mark.

#5: Art at the festival began with the Art Festival

Advertisement

Hide AdLaunched in 2004, the Edinburgh Art Festival is one of the newest players under the festival umbrella, considerably younger than the Jazz & Blues Festival (1979) and the Television Festival (1977). However, those with long memories know that visual art was an important part of the festival landscape from the early days. By the 1950s, Edinburgh International Festival was making a name for itself with blockbuster exhibitions.

They began with Rembrandt in 1950, and big hitters followed year on year: the Spanish Masters, Degas, Renoir. 1954 was a bumper year, including both Cezanne at the RSA, still regarded as one of the best Cezanne shows ever in the UK, and Richard Buckle’s groundbreaking “Homage to Diaghilev” at Edinburgh College of Art, which included (among some 1,000 exhibits) designs for ballet by Matisse, Picasso, Braque and Gauguin.

Advertisement

Hide AdNotable exhibitions continued through the 1960s, including Epstein (1961), over 200 works by Delacroix (1964), and a major retrospective of Charles Rennie Mackintosh (1968). Meanwhile, the Richard Demarco Gallery pioneered shows of contemporary art, including the seminal Strategy: Get Arts exhibition at ECA in 1970, which introduced the work of Joseph Beuys to the UK.

But pressures on funds at EIF meant art began to disappear from the programme, and the large-scale single-artist shows created in the 1950s were no longer possible on any budget. Visual art was struggling for a place on the festival map by the time the Art Festival was launched.

It functions primarily as an umbrella under which to gather and promote the exhibitions happening at galleries across the city (50 in 2019), but there is a small budget for commissioning new work by contemporary artists. In its 17-year history, the festival has commissioned work by artists such as Susan Philipsz, Toby Paterson, Ruth Ewan and Charles Avery, and has also proved adept at opening up hidden or underused spaces in the city.

In 2020, when all Edinburgh’s Festivals were cancelled by the pandemic, the Art Festival found ways to commission work by 10 artists, outdoors, online and in a weekly showcase in The Scotsman, making the paper a (sort-of) festival venue for the first time in its history.

#6: The Book Festival needs Charlotte Square

The first large-scale literary event at the Edinburgh Festivals was the Writers Conference of 1963 under the International Festival banner. Edinburgh Book Fair, the forerunner to the Edinburgh International Book Festival, launched in 1983, run by Jenny Brown who was then working at the Fringe office.

In a tent in Charlotte Square, the event featured 120 authors with headliners John Updike and Anthony Burgess. The festival (as it became) was biennial until 1997, then annual, and the site grew steadily into a tented village hosting some 900 events in 2019.

Advertisement

Hide AdThe highlights are many: Seamus Heaney, Harold Pinter, JK Rowling, Margaret Atwood, Paul Auster, Salman Rushdie, Susan Sontag, Gore Vidal, Amos Oz, Al Gore. Haruki Murakami, who insisted on a private gazebo in which to sign books, Candace Bushnell, who drew a packed house of young women dressed to kill, Muriel Spark reading from The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie.

In 2020, the festival took place online, and 2021 brought the shocking (to many) announcement that there would be no return to Charlotte Square. The festival will remain at Edinburgh College of Art for the next two years, moving to a new site in the former Royal Infirmary building on Lauriston Place in 2024.

Advertisement

Hide AdSo this “myth” is not really a myth yet, it’s still an open question. Will the Book Festival survive without its much loved West End base? Will the Fringe grow even bigger? What impact might this have on the fabric of a city where it is already punitively expensive for ordinary people to live? How will Nicola Benedetti, director-designate at EIF, stamp her identity on the event in the years to come?

The festival will never be static. For as long as this ecosystem survives, there will be ebbs and flows, old questions and new ones, and as the 2022 festival season accelerates towards us, The Scotsman will be here to keep on asking them.

This year we are delighted to be returning to daily Festival magazines in The Scotsman, beginning on Saturday 6 August and running until Saturday 27 August. There will also be five weekly Festival sections in Scotland on Sunday, beginning on Sunday 31 July. The Scotsman's continued and unrivalled coverage of Edinburgh's festivals relies on the generous support of our commercial partners along with our newspaper and website subscribers. Support our mission by subscribing to The Scotsman in print or online at https://www.localsubsplus.co.uk/pg/SCO or by contacting [email protected] about sponsorship and advertising opportunities.