Edinburgh International Book Festival roundup: Alexander McCall Smith | Louise Welsh | William Dalrymple

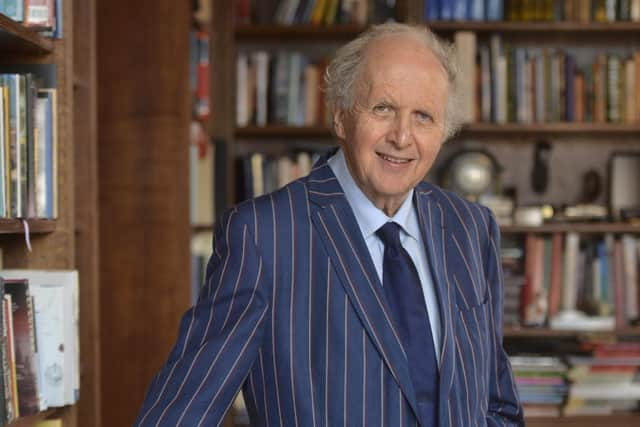

It’s no small thing, being able to cheer up a damp audience on a rainy Tuesday morning in Edinburgh, let alone doing so in such a cavernous venue as Central Hall. You (I presume) or I (certainly) could not do this, and definitely not if we had been up till 4 o’clock in the morning, so it’s entirely reasonable to wonder why Alexander McCall Smith can.

The reason for such a late night is that he was finishing the next volume of 44 Scotland Street, soon to run on these pages. One key change, he hinted, was that he might well ignore “the statistical evidence that Edinburgh has the UK’s highest ratio of pushy mothers” and make Bertie’s mother Irene mildly mellower. More surprisingly, we might soon find former narcissist Bruce joining the monks of Pluscarden abbey.

Although the event, expertly chaired by James Naughtie, touched on the many other books this most prolific of writers produces – his short collection, The Exquisite Art of Getting Even, is fresh off the presses – questions seemed to swing round to Scotland Street. McCall Smith recalled one well-meaning American lady assuring him that he was bound to be a lot more successful posthumously. To another, who inquired when he was going to bring 44 Scotland Street to an end, he replied that there would, of course, be a time when he would no longer be around. “Oh,” she said. “And when is that going to be?”

Whether or not you agree with her politically, Nicola Sturgeon makes a very good Book Festival chair, and her questions to Louise Welsh were thoughtful and based on a knowledge of the writer’s work that clearly extends well beyond the two Rilke novels. “As a reader,” the First Minister said, “I will forgive a badly written plot before a badly written character,” singling out Rilke as an exemplar of a credibly three-dimensional creation. The key to that, Welsh said, is empathy, just as the key to writing itself lies in listening to your inner voice.

William Dalrymple is our best narrative historian, as well as our most groundbreaking one, opening up a whole subcontinent’s worth of neglected stories. His four biggest doorstoppers from the last two decades – now marketed as the Company Quartet – tell the story of how the East India Company, which 100 years into its history employed a mere 35 men in its London headquarters and 250 in the field, became the world’s first multinational company. On top of that, it ran a narco empire massively bigger than Pablo Escobar’s, virtually invented corporate lobbying, had a private army twice the size of Britain’s, and ultimately took over India, its power only ending after it provoked the biggest uprising against colonialism in the whole of the 19th century.

Ah yes, the Indian War of Independence, or as we call it, the Mutiny. We tend not to hear about the massacres its suppression involved because we prefer to think we left a benign legacy of railways, courts and cricket: India through the Merchant Ivory lens. The reality of empire, Dalrymple points out, were – as they always are – to do with brutality and exploitation of the colonised, yet when writers like David Olusoga and Sathnam Sanghera mention this, they are told to stop writing about the subject and are even threatened with violence. He himself isn’t, though he’d generally agree with their analysis; the only difference, he said, is that he is white and they are not. “My plea is that we should all just learn this stuff. None of it should be a politicised matter.” Amen to that.