Edinburgh International Book Festival interview: Radical forgiveness with Em Strang

What does it mean to forgive? To forgive a violent and destructive act, even a murder? To do an act of mercy for a person who has done you grievous wrong? Could you forgive in the worst of circumstances? Could I?

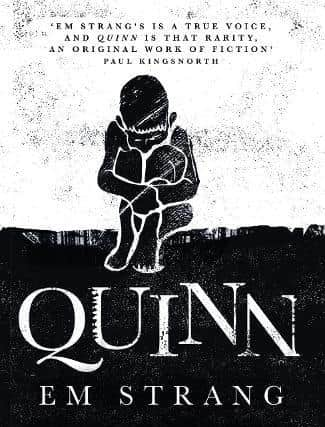

That’s the question Em Strang was asking herself as she wrote her first novel, Quinn, about a man who has committed a terrible crime and the woman who chooses to forgive him. She’s still asking it, she says.

Advertisement

Hide Ad“I don’t have any answers to this question. I feel like I’m asking it over and over again [in the book], trying to move towards it, then getting pushed away from it because I can’t figure it out. I’m still in that process of trying to work out what forgiveness really means. If I were Jenny, what would I do? Would I be able to do something like what she did?”

Strang, 52, is an award-winning poet, and Quinn, published by Oneworld in March, is her first novel. She speaks to me on Zoom from Argyll where she and her husband are building a small, off-grid, low-carbon-footprint home. As a writer whose main preoccupations to date have been “nature and spirituality”, she sounds almost surprised to have written a novel about “incarceration, male violence and radical forgiveness”.

When the book begins, Tomás Quinn is incarcerated for a violent crime against his girlfriend Andrea which he says he didn’t commit (or perhaps can’t remember committing). It’s clear from the start that Quinn is an unreliable narrator. His grasp of time is ever shifting (“five years had passed, or the sun and moon had tricked me” is his description of most time periods), and one begins to suspect his account of his prison experiences is not grounded in reality either. But the story’s most extraordinary twist happens when Jenny, Andrea’s mother, gets in touch.

Strang says Quinn’s voice simply arrived in her head speaking the first line of the novel. She spent the first few months of writing simply listening to that voice. “I had to trust, I had to let go an awful lot and just write, let the imagination do its work. There was a lot of thinking and feeling my way into that voice and listening to how he wanted his trajectory to go. It was only afterwards I could get a deeper understanding of what was going on.”

She suspects the book was “composting” for the ten years she spent teaching creative writing in a Scottish prison, a period she describes as “transformational”. “In ten years, I think I went from a place of thinking, ‘These men must be evil and therefore they’re not like me’ to ‘Oh, we’re maybe not that different’, to, just before I finally left: ‘Oh sh*t, we’re just the same. I haven’t done what they’ve done, but the potential is totally within me.’

“In our culture, often we don’t want to acknowlege that the perpetrator is also a human being. It’s much easier to imprison them and forget about them and delineate them as monsters. I write about Quinn in a way that is neither condoning nor letting him off the hook. I just wanted to show these different aspects of what it means to be human, Solzhenitsyn’s idea that the line between good and evil goes through the centre of every human heart. It does. I think that’s one of the things working in prison has taught me.”

Advertisement

Hide AdStrang began writing as an unhappy teenager at boarding school “as a tool for escape and healing, although I wouldn’t have called it that at the time”. Healing has been an important theme in her work ever since. Through her 20s and 30s she got up at 6am every day to write for 90 minutes, but did not submit work for publication. “I think that was my training, reading other writers, and writing, writing, writing, writing, learning the craft.”

In 2013, she completed a PhD in ecological poetry at Glasgow University, one element of which was to work on her first poetry collection, Bird-Woman, which was published in 2016 and won the Seamus Heaney Best First Collection Prize and the Saltire Poetry Book of the Year. A second collection, Horse-Man, followed in 2019, and a third, Firebird, is currently “being tweaked”. A second novel is also underway.

Advertisement

Hide AdShe’s intrigued that her poetry and prose have followed very different paths. “This wasn’t a conscious decision, but it feels like my poems are about excavating love, mystical love, human love and a love of nature, and my prose is a kind of excavation of evil. Totally different frameworks, but they both feel necessary in their different ways.”

She says she lives as “green” as possible, but that the relationship between creativity and activism is complex. The issue hangs over this year’s Book Festival after climate activist Greta Thunberg cancelled her appearance claiming that a major festival sponsor, Baillie Gifford, invested in the fossil fuel industry. Last week, more than 50 authors signed an open letter calling on the festival to drop any sponsor with such investments.

Strang says: “I struggle a lot with the kind of didactic activism that is polarising. It sets up a ‘them and us’ scenario. There’s a tendency for the holier than thou to step in, which just exacerbates the problem.

“I would like to try to get into a more unitive mindframe where I can see that my life is reliant on fossil fuels in many ways, because all of our lives in the industrial west are reliant on fossil fuels; we’re in that circle and organisations like BP and Shell and even Baillie Gifford are in the circle with us – or we’re in the circle with them. Then I think we can start having conversations that might move things forwards.

“There is no clear answer. It’s not that I can do this or that and it’ll be fine. It’s a monumental mess. I actually think that one of the main answers, if there is an answer at all, is a spiritual answer which is to change our minds and our hearts on a big scale. I don’t want that to be a cop-out either: they have to go hand in hand. I think activism without spirit, without heart, is pointless, and heart without activism is just waffly. You have to have both.”

Em Strang appears at the Edinburgh International Book Festival on 24 August, 4.30pm with Heather Parry, www.edbookfest.co.uk