Edinburgh Festival Fringe theatre and musicals reviews: Jacob Storms’ Tennessee Rising: The Dawn of Tennessee Williams | Tennessee, Rose | The Ballad Of Truman Capote | 2020 The Musical | Two Tigers

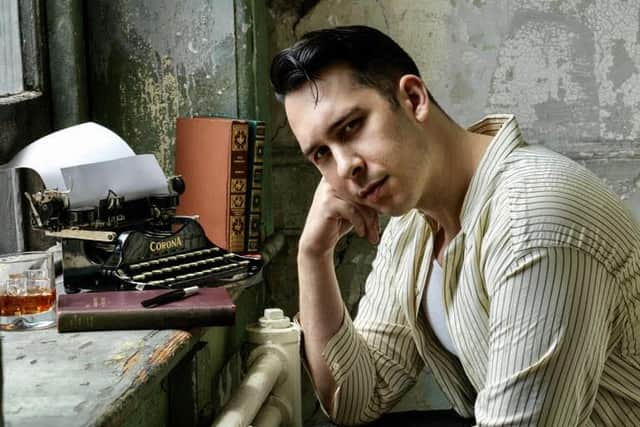

Jacob Storms’ Tennessee Rising: The Dawn of Tennessee Williams ****

Assembly Rooms (Venue 20) until 27 August

Tennessee, Rose ***

Pleasance Dome (Venue 23) until 28 August

The Ballad Of Truman Capote ***

theSpace @ Niddry Street (Venue 9) until 26 August

In this age of cultural upheaval and reassessment, the interest in the lives of famous writers - and how they treated their partners, families, lovers - often seems to eclipse any real engagement with their work.

Advertisement

Hide Ad

Just occasionally, though, a biographical show emerges with the confidence and wit to treat the work as what it invariably was, an integral and vitally demanding part of the life; and the US writer and actor Jacob Storms’s Tennessee Rising, originally directed in the USA by Alan Cummings, is one of those shows, a short, deep, and perfectly made one-hour narrative of Williams’s escape from his difficult southern childhood into the world of 1930’s literary America, and into eventual fame and fortune.

The ties that bound Williams to that southern past are fully acknowledged, of course; the Williams of Storms’s play fully recognises his own betrayal and abandonment of his vulnerable sister Rose, and the way in which he uses her pain in creating his own theatrical success.

In Tennessee Rising, though - and in Storms’s brilliantly charismatic performance - we also meet the agents, producers, lovers and friends who played a key role in propelling Williams to fame; and it seems, too, that we truly meet the writer himself, proud, beautiful, strong in his resistance to the rising tide of 1930’s fascism, and steely in his determination to write and to keep writing, at all costs.

Clare Cockburn’s Tennesse, Rose, by contrast, approaches Williams’s life from the opposite angle, focussing on the tragic story of his sister Rose, who after a rebellious youth found herself increasingly labelled as mentally disturbed, and who lived out her long life in an institution.

In the end, the play suffers from the same difficulty as the friendly nurse, brilliantly played by Helen Katamba, who tries to help the elderly Rose reconnect with her memories; in that it’s drawn to Rose because of her famous brother and his plays, but in the end has to focus on Rose herself, about whom much less is known.

Yet Patrick Sandford’s delicate and heartfelt production offers plenty of food for thought for those interested in the social forces that helped destroy Rose Williams; with Anne Kidd, as Rose, a poignant elderly presence, reliving both the pain and the joy of a tempestuous youth.

Advertisement

Hide AdThe writer, actor and socialite Truman Capote was a decade younger than Tennessee Williams; and like Williams, he was a gay man who worked his way to fame and wealth from a relatively humble southern background.

In Andrew O’Hagan’s Ballad Of Truman Capote, though, we learn precious little more about Capote and his genius, as - with some help from the art of the rhyming couplet - he swans around his suite at the Plaza Hotel in New York on the night of his legendary 1966 masked ball, preparing to don his mask and go downstairs to join his dazzling celebrity guests.

Advertisement

Hide AdThe difficulty for the audience, though, is that Patrick May - as Capote - is already effectively wearing a mask, in the shape of the perfectly-honed but somehow lifeless impression he delivers of Capote’s famously mannered voice and style; and the combination of that heavily veiled performance, and a script which lacks dramatic energy because it offers no clear sense of connection with the audience, makes this a show that touches on Capote’s life and work, but barely illuminates it at all.

Joyce McMillan

2020 The Musical ***

Underbelly, Bristo Square (Venue 302) until 27 August

Like a greatest hits collection of cultural references that would have left us perplexed four years ago, this merry musical sits firmly on the lighter side of lockdown.

Following two young actors, Adam and Emily, as they go from rehearsing their new show to, respectively, working in a care home and at Lidl, it’s a piece that has the potential to go full metatheatrical, but instead opts for a small-scale will-the-won’t-they (be allowed to) have a romance, set in a world crisis that is frequently defined by ever-changing restrictions on daily, domestic life.

Oly Britten risks stealing the show during a turn as Boris Johnson, but writer Natasha Mould’s light observations capture a chorus of voices in a way that also touches on government hypocrisy and mental health as well as, when Adam’s grandfather becomes ill, the awful way people were separated from their dying relatives.

As in real life, things start to flag a bit during lockdown 2, or is it 3. Make the most of things is the familiar message at the end, but it’s one that’s given extra poignancy due to being delivered to an audience back at the Fringe (almost) like none of the above ever happened.

Sally Stott

Two Tigers ***

C Aquila (Venue 21), until 26 August

Sue Casson’s chamber musical about New Zealand-born writer Katherine Mansfield is revived on the Fringe to mark the centenary of her death. We find ourselves in Bandol on the French Riviera, where Avril Gilchrist is making a podcast from the hotel where Mansfield stayed in 1915 when she was grieving after the death of her brother in the First World War.

Advertisement

Hide AdGilchrist reads snatches of commentary and stories in between the songs, the best of which have a delicate, poignant quality. Lily Casson (Mansfield) has a beautiful singing voice. Lucas McQueen plays John Middleton Murry, her editor and lover (they are the two tigers of the title, shaking up literary London with the spirit of modernism) and Emily Mahi’ai plays a number of other parts, including Mansfield’s female lover, Ida Constance Baker, who makes a surprise appearance two-thirds in.

The complex plot is confusing at times, and heavy with historical detail, but we’re back in Bandol in 2017 with Mansfield, who is now ill with TB. It’s hard to do justice to this mercurial heroine, but at its best this show does offer flashes of her lively intelligence, sardonic wit and adventurous spirit.

Susan Mansfield