Edinburgh Book Festival: Sebastian Barry on using fiction to fill in history's gaps

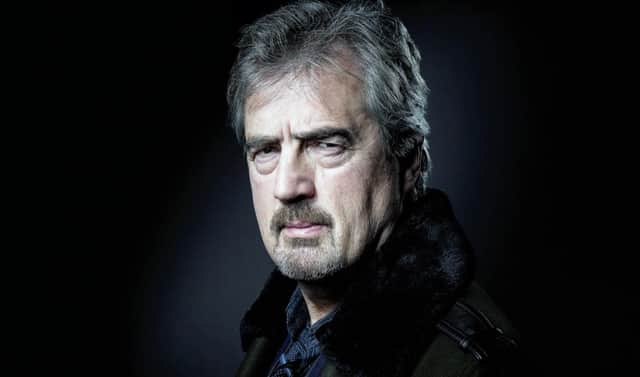

Sebastian Barry appears on my computer screen in his study, sitting, he says, in “the very seat” from which he will address his Edinburgh International Book Festival audience. But even in a world of Skype and online book festivals, Barry has an antenna tuned to the past.

He tells me about his home, a former rectory in the Wicklow mountains. That the room directly above him was the maid’s room, and that the 1901 census recorded two maids, sisters. By 1911, there was only one. A gap in history. A story.

Advertisement

Hide AdBarry’s lifelong work as a writer has been to bring to life the stories in the gaps. All his protagonists come from the margins of his own family history: a great aunt incarcerated in an asylum (The Secret Scripture), a great uncle who fought in the First World War (A Long, Long Way), and so on. “All these full lives thrown on the scrapheap of time, and you become a writer and you think, I’m not going to allow the erasure of these people, I’m going to try to make them up.”

His ability to weave stories in the gaps of time has made him one of Ireland’s pre-eminent novelists, twice shortlisted for the Booker Prize, twice winner of the Costa Award and the Walter Scott Prize, and currently Ireland’s Laureate for Fiction. He is also an acclaimed playwright - his play, On Blueberry Hill, opened on the West End in March, running for four “glorious” days before lockdown began.

His new novel, A Thousand Moons, revisits the same characters as his Costa-winning Days Without End, though he prefers not to use the word sequel: “A sequel sounds like ‘Let’s make some money out of Die Hard 2’. Of course that was rather a good film because Alan Rickman was in it!”

Each book requires a year of research, but that isn’t enough. Barry believes the writer must wait for the character’s voice. “Sometimes, the worst thing a writer can do, in my opinion, is write. You really have to be seeing and hearing, taking it down as best you can. I was sitting there for nine months waiting for Thomas (McNulty, the narrator of Days Without End). Waiting like an idiot. But I think accessing the idiot part of you is quite an important thing for a writer.”

When Thomas did arrive (he was a great-great uncle who “fought in the Indian wars”) it was with a voice so alive and expansive it was exhilarating to write. Fleeing the Irish famine at 15, Thomas becomes a soldier, first in the Indian campaigns, then the American civil war, the brutality he experiences matched only by his love of life and his devotion to his partner, fellow trooper, John Cole.

The book is dedicated to Barry’s son, Toby, who came out to his parents shortly before it was written. “Very, very bravely, as it turned out,” Barry says. “He was 15, and it was so hard for him but at the same time it was so magnificent. It would never have occurred to me that they (McNulty and Cole) would be in love with each other until then.

Advertisement

Hide Ad“I had a feeling, when I began the book, that this would be the easiest book in the world to screw up, because I’m not gay, I have no qualifications to write it. I told myself, don’t get it wrong, be as brave as your son. It took courage to make that book, I have to be honest about it.”

A Thousand Moons picks up the story in 1870s Tennessee where McNulty and Cole are helping work a farm belonging to an old army buddy with their adopted daughter Winona, a Lakota Indian orphaned when their company attacked her people, and two freed slaves. But America in the aftermath of the civil war is a hotbed of racial violence, and this unconventional family has no shortage of enemies.

Advertisement

Hide AdThis time, Winona is the narrator, and Barry waited for her voice too. “I was wondering, would she want to use again this stupid person here in Wicklow to give her own account. Could I go back to the 1870s and truly listen to and understand a 17-year-old woman? I was quite prepared for her not to say a word, then she said three words: ‘I am Winona.’ Just that. As if she had phoned me, or come to see us. I was so excited I called my editor.”

Winona is coming of age in a world which regards her as an outcast - “it wasn’t a crime to kill an Indian because an Indian wasn’t anything in particular”. She must come to terms not only with the brutal treatment wrought against her in the present but with the violent extermination of her people.

“I think it’s a novelist’s out and out duty to look everything square in the face,” Barry says, “to clear off the fog around things. Essentially, the American project was a colonial project and the sufferers of that were perhaps 10 million people, we don’t even know how many. I can’t write about Winona without noticing that first.” He says his next novel will be set in Ireland, but he hopes to return to Winona’s world, and is reading up about freed slaves.

One of the most remarkable thing about both Days Without End and A Thousand Moons is that, while absolutely rooted in their own time, the stories touch on contemporary concerns. If Days Without End touched on gender fluidity (Thomas McNulty dresses female for a music hall act, and is comfortable living as a woman) A Thousand Moons has echoes of the MeToo movement and Black Lives Matter. What resonates is how little has changed in 150 years.

“Things don’t get better,” Barry says. “It makes me mad. The reluctance people have to discard their racism is in itself an extraordinary atrocity. They don’t want to set it down on the ground because then they don’t feel as happy as they did when they were harbouring those views. What is that? We could talk about that for three thousand years and not get the answer to that.”

A Thousand Moons is published by Faber & Faber. Sebastian Barry is appearing online as part of the Edinburgh International Book Festival on 28 August, see https://www.edbookfest.co.uk/

A message from the Editor

Advertisement

Hide AdThank you for reading this story on our website. While I have your attention, I also have an important request to make of you.

With the coronavirus lockdown having a major impact on many of our advertisers - and consequently the revenue we receive - we are more reliant than ever on you taking out a digital subscription.

Advertisement

Hide AdSubscribe to scotsman.com and enjoy unlimited access to Scottish news and information online and on our app. With a digital subscription, you can read more than 5 articles, see fewer ads, enjoy faster load times, and get access to exclusive newsletters and content. Visit https://www.scotsman.com/subscriptions now to sign up.

Joy Yates

Editorial Director