Don’t look back in anger: Scotland and Britpop

NINE pm. 11 August, 1996. The dying light of a summer’s night. One hundred and fifty thousand people, sweat running off them, their ears ringing from a day’s worth of music – The Prodigy, Ocean Colour Scene, The Manic Street Preachers, The Charlatans – all waiting in a state of suspended animation for the most popular band since The Beatles to appear. Then a deafening roar as the Gallagher brothers take the stage. Looking out over banks of fans, stretching as far as the eye can see, Noel shouts: “This is history. This is history. Right here. Right now.”

Even today, there’s no arguing with that. Oasis’s two consecutive Knebworth gigs – the fastest-selling concerts ever – marked the apotheosis of Britpop, a phenomenon which saw the Gallaghers and groups such as Blur, Suede, Pulp, Supergrass, Elastica and Sleeper – redefine Britishness and restore a sense of national pride. No longer was being “British” associated with royalty and Spitfires and Empire, but with cigarettes, swearing, Fred Perry polos and parkas.

Advertisement

Hide AdWith their reverence for the country’s rich pop heritage, self-conscious rejection of US culture and their (mostly) working class credentials, they made it cool to come from the UK again. And they reclaimed the Union flag. An ensign that had become a cringe-worthy remnant of colonialism suddenly had street cred. It appeared everywhere: on albums, posters, guitars and the front covers of NME and Vanity Fair magazine – which showed Liam and Patsy Kensit, John and Yoko-like, lying on Union flag-emblazoned bedding. No wonder the Labour Party saw the Gallaghers, Damon Albarn and Jarvis Cocker, and the wider Cool Britannia movement they spawned, as the perfect ambassadors for its regeneration after 18 years of Tory rule.

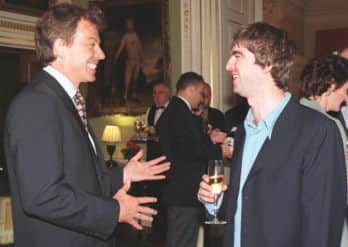

At those Knebworth gigs – which one in every 20 people in the UK sought tickets for, with me being one of the lucky ones – that feeling of optimism and fraternity was crystallised; for a fleeting moment, the entire country seemed to share a sense of identity. But the concerts in the grounds of the stately home in Hertfordshire (and to a lesser extent the Loch Lomond gigs which preceded them) also exposed the contradictions in Britpop. What was once edgy and subversive became boorish and bloated. The hunger to make music yielded to a pursuit of money and acceptance by the establishment. Seven months before Noel was invited to 10 Downing Street and a year before the release of the critically panned Be Here Now, the movement was already a victim of its own success.

From today, BBC Radio Two, Four and Six Music are marking the 20th anniversary of Britpop with a series of documentaries, interviews and a Top 30 countdown. Taking two events – the death of Kurt Cobain (and arguably grunge) and the first time Oasis played live on Radio One – as their starting point, the programmes will trace the rise of the movement from the release of Blur’s Parklife through Pulp’s seminal performance of Britpop anthem Common People at Glastonbury to its demise after the release of Radiohead’s OK Computer and the death of Princess Diana. Oasis’s manager Alan McGee and Andy Ross, head of Blur’s record label, will also be giving an insight into the infamous Battle of the Bands, when Roll With It and Country House fought to reach No 1 (Country House won the battle, but Oasis won the war, with (What’s The Story) Morning Glory? eventually outselling Parklife). But the mass celebration also affords the opportunity to ask deeper questions about Britpop and its legacy, and the relationship between pop music and national identity, at a time when it is more relevant than ever.

Though the lustre of Britpop faded faster than Liam’s congeniality, the sense of Britishness it generated was conjured up again by Danny Boyle for the London Olympics opening ceremony. Boyle’s vision was more complex and inclusive, but it used British pop music from the past 50 years to whip up a sense of patriotism, with David Bowie’s Heroes playing as the athletes entered the stadium. One of the fears of the SNP was that this spirit of solidarity would outlast the games and influence the referendum debate. So why hasn’t the No campaign used pop music to the same effect? Bowie’s fleeting Brit Awards comment and comedian Eddie Izzard’s Better Together fund-raiser aside, the exploitation of popular culture has been minimal.

Then again, you could ask, was the movement ever really as “British” as it pretended? As writer and independence campaigner Alan Bissett, an expert in Britpop, points out, John Harris’s definitive book on the movement The Last Party is subtitled, “Britpop, Blair and the Demise of English Rock”. Given its stars were almost exclusively white and English, and predominantly male, could Britpop be considered less an expression of a shared identity than a demonstration of how one culture within a nation state can subsume all others?

More than any other musical movement before or since, Britpop represented a homage to the past. Magpie-like, its chief proponents plucked bits and pieces from the great rock bands of the 60s and 70s – the Beatles, the Kinks, the Sex Pistols, The Who. Sometimes this came perilously close to plagiarism (Elastica were sued by both Wire and The Stranglers), but mostly it was a case of paying tribute.

Advertisement

Hide Ad“Those first few albums from Blur, Suede, Oasis, Pulp and Elastica were just great albums, so musically it felt as though something really exciting was happening,” says Bissett. “The early 90s had been a bit of a graveyard for good new music. It was all cheap, tacky dance songs and Take That, and grunge never really spoke to me either. It was American so felt quite distant.

“But Britpop felt a bit closer. I was quite into the 70s when I was at school, though it was before my time. I was into T-Rex, Queen and Pink Floyd and a lot of those sounds had come back but made by people of my generation.”

Advertisement

Hide AdIt might seem odd that Bissett, now a prominent Yes campaigner, was so smitten with an aesthetic which promoted a sense of Britishness, but at the time he didn’t find it alienating. “Back then, I didn’t really have a political consciousness so I didn’t care about the fact it came draped in the Union Jack,” he says. “Because it was seen as a fight back against American cultural dominance, it didn’t feel chauvinistic. It was supplanting manufactured pop so it seemed subversive.

“There was also a strong working-class element to it – me and my friends it felt as though it was about us.”

This was the appeal of Britpop to many people; a sense that pop belonged once again to the common people, as referenced in Pulp’s biggest hit. And it brought us some unmissable moments; not only did its music – which provided the backing tracks to zeitgeisty films such as Boyle’s Trainspotting – define the era, but its stars were consistently entertaining, prone to feuds, public outbursts and the occasional stunt, like Cocker invading the stage during Michael Jackson’s performance at the 1996 Brit awards.

“Britpop was more than Blur v Oasis. The explosion of alternative home-grown talent, of genuine British stars, forced the UK mainstream to change the way it viewed indie music,” journalist Miranda Sawyer has said.

Even early on, however, there was evidence of Britpop’s fatal flaws. It always tended towards the laddish (many of the women involved were avowedly anti-feminist) a characteristic which increased as Suede’s sexual ambiguity gave way to Oasis’s relentless blokieness and lads’ mags like Loaded hit the supermarket shelves.

Then there was its claim to “ordinariness”. Britpop stars prided themselves on being on the same level as their audiences so Cocker could sing: “You’ll never watch your life slide out of view / and then dance and drink and screw / because there’s nothing else to do” convincingly. But, as they became more successful, they became caught up in the pursuit of cash and celebrity, so Oasis’s third album choked on a surfeit of cocaine and Cocker topped the Sun’s liggers league. Tied to this, of course, was the way in which they were co-opted for political purposes. Though in retrospect the Britpop/Blair alliance seems misconceived, the Labour government rode into power in May 1997 on a tidal wave of optimism and the sight of pop stars hobnobbing with the Prime Minister seemed only to confirm the dawning of a new age. It didn’t take long, however, for project Cool Britannia to self-destruct.

Advertisement

Hide Ad“Oasis, as colossal as they were, were not speaking for the underclass any more, they were absolutely part of the establishment,” says Bissett. “ Things as disparate as [the Gallaghers] and Tony Blair and the City of London – and then Vanity Fair getting in on the whole thing – they all just slid into each other and it became this smooth marketing campaign and became about power and money.”

In the end it backfired on both parties as Britpop imploded and the Labour government was tarnished by its decision to go to war with Iraq. At the Brit Awards in 1998, John Prescott had an icy bucket of water thrown over him by Danbert Nobacon of Chumbawamba.

Advertisement

Hide AdA broader cultural flaw was that the sense of Britishness Britpop conjured up was largely an illusion. The movement didn’t encompass a single Scottish band, although, as Britpop faded, groups such as Belle and Sebastian, Arab Strap, The Supernaturals, dubbed Cool Caledonia, were coming to the fore.

To see the extent to which Britishness and Englishness were conflated you only have to look at the frenzy around the Euro ’96 Championships when Three Lions (Football’s Coming Home) seemed to be played everywhere on a loop. Hosted by England, the event seemed to play to the same working class audience and generate the same blokeish atmosphere as a Britpop gig, but without the pretence of encompassing the whole of the UK.

“There was a special Britpop edition of NME a few years ago and in the introduction Steve Sutherland, who was editor in the Britpop glory years, said the high point for him was England defeating Scotland at the Euros – so you do have to ask, how British was it really?” says Bissett.

Perhaps this superficiality is the reason politicians and the Better Together campaign have shied away from using pop music to persuade Scots about the benefits of staying in the Union, although Alistair Darling did dip his toe in the water when he said a Yes vote would mean “British music would no longer be our music”. Or perhaps it’s because the Blair government’s short-lived flirtation with rock stars taught them a lesson.

Then again, it could simply be their polls have taught them Scots see themselves as Scottish, as opposed to British, and are chiefly concerned about the future of the economy. Hence no Union flags, no Britpop and a focus on the prospect or otherwise of a currency union.

Those who were at the heart of Britpop have mixed emotions about its heyday. Justine Frischmann, Albarn’s one-time partner and the former leader of Elastica, once said: “The whole thing was so bitchy. I always feel kind of dirty after I’ve talked about [it]. A bit tainted, somehow. Even at the time, it seemed vaguely nauseating.”

Advertisement

Hide AdWith the benefit of hindsight, it is clear the new era it appeared to usher in was an illusion, that though it produced an plethora of brilliant songs – Don’t Look Back In Anger, Champagne Supernova, Parklife, Sorted For E’s & Wizz and many more – it was ultimately empty.

Still, empty or not, there are many people across the UK, who like Bissett, look back with a great deal of nostalgia to that brief period 20 years ago when Britpop’s star shone. So what if it turned out to be just 150,000 people standing in a field. For a while it felt like the future’s meant to feel and made ordinary people believe they might live forever.

Twitter: @DaniGaravelli1