Charting classical music traditions in danger of dying out

What is classical music? It’s a question that vexes many of us in terms of definition. So imagine how much more interesting the question becomes when you ask: “what are the classical musics”?

That’s essentially what the critic and world music specialist Michael Church has turned his mind to in The Other Classical Musics: Fifteen Great Traditions, a fascinating new book he has spearheaded and edited along with an army of expert contributors in the field of musical traditions from different parts of the world.

Advertisement

Hide AdPurely in terms of content, it’s a revelation to read about the influence of the Indonesian Gamelan tradition on Balinese and Javanese life, a musical lineage embracing amateurs and professionals and reflective of Javanese social concepts of ownership and shared artistic activity; or to see the impact political unrest can have on centuries of musical tradition, highlighted by the fact that 80 per cent of court musicians were wiped out when the Khmer Rouge ousted Cambodia’s King Sihanouk in 1970.

It may seem strange that American Jazz occupies its own chapter, while South America is omitted, but Church reckons that, with so little known about music during the Aztec Empire, South America falls under the category of “newly-formed societies” which lack “the conditions required for the evolution of a classical music”.

Selection issues aside, in all the musical traditions that Church’s experts do explore, from China’s beautifully fragile Guqin zither music to the surprising swathes of musical heritages found in Africa, the Eastern Arab world, Iran, Uzbekistan and Tajikstan, there are fundamental underlying commonalities in terms of sustained history and development, systemised theory and practice, and the varying but real consequences of social and political change.

This is what allows Church to promote the idea of there being many classical musics, not just the hegemonic Western one of Palestrina, Beethoven, Schoenberg and the rest. But in order to articulate that, a definition is urgently required, and Church gives us one in his comprehensive introduction.

Why use the word classical at all? The term “art music” is too broad, he says, as all music is a form of art. So “classical” it is, being the term “best capable of covering what every society regards as its own Great Tradition.”

Above all, he continues, “a classical music will have evolved in a political-economic environment with built-in community… where a wealthy class of connoisseurs has stimulated its creation by a quasi-priesthood of professionals”. That’s as easy to appreciate in terms of the roles played by the the early church and aristocratic courts and their musicians in fostering the European classical tradition as it is in defining the age-old gagaku court music of Japan.

Advertisement

Hide AdMore important, perhaps, is the time and space such an environment gives musicians to develop rules for composition and performance. “The evolution of a canon of works, or forms; indeed the concept of a canon validated by a system of music theory, is a defining feature of all classical music,” Church argues.

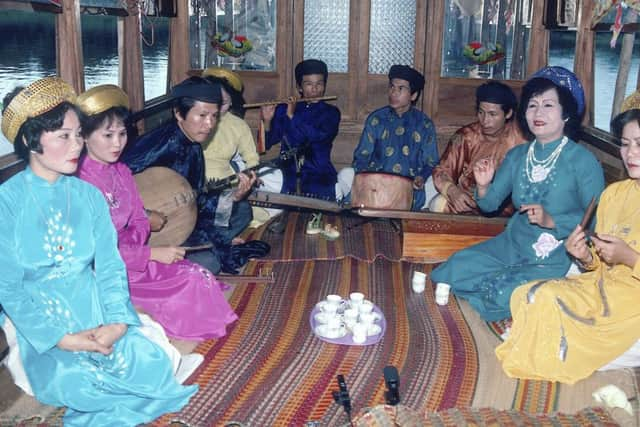

And so we find, throughout this book, constant affirmation of that view. In just about every one of the 15 classical musics there exists an organised system of notes, the beauty of which is that they are not all the same. Unlike our equal-temperament scale, which is divided neatly into 12 equal semitones, thus defining our familiar major and minor scales, the South East Asian music of Thailand, Cambodia and Vietnam uses a seven-note scale, in contrast to the Indonesian pentatonic system, whose equidistant intervals lie somewhere between a whole tone and a major third. Even American jazz, with its flattened blues notes, has its own scale system.

Advertisement

Hide AdWhat we’re really looking at are varied theoretical manifestations of a universal modal principle, a system which, says Church, “implies a specific melodic pattern in which some notes have more pulling power than others.” The differentials define individual identities.

As to the “canon of works”, in just about every tradition cited, you find extended structures that range from variation-technique to multi-movement suites. The Javanese word Gendhing, writes Indonesian expert Neil Sorrell, refers to the largest and noblest of Gamelan compositional structures, “rather as we have symphony or concerto”.

Church doesn’t shy away from addressing the threats that many of the eastern traditions face, not just from social and political upheaval, but from the homogenising influence of Western music. It’s a sign of panic, perhaps, that Unesco has stepped in, slapping protection orders on endangered musical species. The implication is that, in the absence of living and self-sustaining musical traditions, unique, time-served musics such as the Uzbek-Tajik shashmaqom will simply end up as “museum culture”.

And what will happen in Syria, to take an obvious current example? It is home to a significant North African classical tradition that goes back eight centuries, but the majority of players have fled its musical epicentre, Aleppo, and the music is silent. The situation is touched upon, but all-too-current to enable adequate up-to-date appraisal.

This book is vitally important in bringing the world picture to our attention, and broadening our understanding of the term classical music.

• Other Classical Musics: Fifteen Great Traditions is published by Boydell and Brewer, £25