Brian Wilson: Anti-Gaelic prejudice is still alive in Scotland

What is it about Gaelic that brings out the playground bully in a steady stream of Scottish commentators who, on other matters, would preen themselves on the liberalism of their opinions? The front page of a Scottish newspaper this week carried the ludicrous, patronising teaser: “Does Gaelic matter? Let the battle begin.” And who, pray, has decreed that a “battle” is required to determine whether a language, far less the people who speak it, “matter”. And matter to whom?

It was appropriate that this appeared on the same day as a report which dismantled the idea that Scotland is less racist than other parts of the UK. One reason for this delusion, it suggested, is that anti-Catholic bigotry has been classified as “sectarianism” rather than racism, where it belongs.

Advertisement

Hide AdHostility to Gaelic, and hence to Gaels, might be placed in the same category. It has been going on for centuries within Scotland but even then it seems remarkable that in the year of grace 2018, it is deemed “normal” to question the very right to existence of a linguistic and cultural minority.

“Does Urdu matter? Let the Battle Begin.” “Does Polish matter? Let the Battle Begin” ... It is inconceivable that such headlines would appear. Nor should they. Yet Gaelic retains its appointed status as a punch-bag for prejudice within the only society on earth that can determine whether it will live or die.

The Gaelic scholar John MacInnes has written of the “remarkably consistent hostility to Gaelic” through the ages. To much of Scotland, via both church and state, the Gaels were always “the other” and the answer lay in eliminating the linguistic distinction. The miracle is not that Gaelic is weak but that it has survived at all, in the face of what history has thrown at it.

The latest twist in a very old tale involves efforts on both fringes of the Scottish constitutional issue to turn Gaelic into its adjunct. This is another travesty in the making and should be nipped in the bud. There is nothing worse for a minority language than to be captured as a political totem and rendered divisive on that basis. We do not have to look far for confirmation. The government of Northern Ireland remains in abeyance largely because of an absurd argument about the status of the Irish language. Sinn Fein wants to capture it. The DUP is so intellectually dim that it has dug itself into the stand-off.

Scotland – and particularly those who have Gaelic’s interests at heart – would be mad to allow the same kind of division to develop, as a by-product of the constitutional debate. Over the past 40 years, to my certain knowledge, all political parties have been supportive of Gaelic and that is how it must remain.

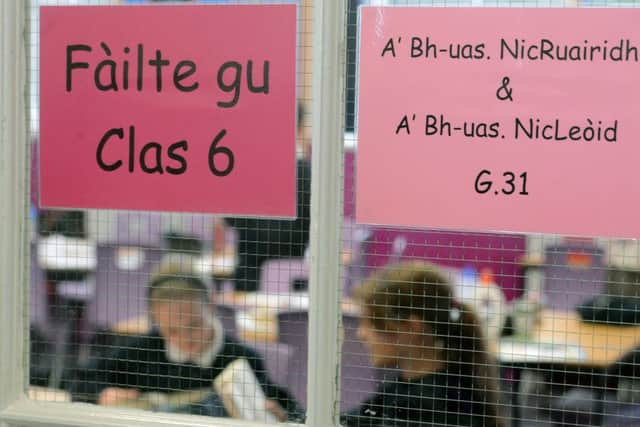

In the early 1980s, George Younger created a ring-fenced budget within the Scottish Office to allow for the development of Gaelic-medium education. This was absolutely crucial and has survived to the present day. The Tories also created the Gaelic Broadcasting Fund which was the first vital step towards the creation of a television channel.

Advertisement

Hide AdAlso in the early ’80s, I wrote a Gaelic policy for the Labour Party built around three pillars – education, broadcasting and status. These were the days of the big Labour-run regions and along with the excellent Colin Spencer, a Mancunian who worked for An Comunn Gaidhealach, we met councillors from them all.

Malcolm Green, the erudite chairman of education in Strathclyde, needed to be convinced of the intellectual case for Gaelic, but once that was achieved he put the full weight of that mighty authority behind it, carrying on a tradition of support for Gaelic education which has existed in Glasgow since the 1940s.

Advertisement

Hide AdIn Lothian, outstanding councillors like John Crichton, Phyllis Herriot and Eric Milligan, with absolutely no prior knowledge of the subject, listened, were convinced and acted with enthusiasm. The success of Gaelic at James Gilliespie’s and then a dedicated primary school became a source of great pride.

I remember a meeting with Central Region where the education chairman represented a mining village. “I’ve folk who can’t afford to put shoes on their children’s feet,” he said, “and you’re asking us to spend money on Gaelic ... but if it’s party policy, we’ll do it.” And they did. With parallel developments in the Highlands and Western Isles, foundations were laid for the current Gaelic-medium network.

One problem with the foolish binary argument about being “pro-“ or “anti-“ Gaelic is that it closes down necessary debate about priorities. When Holyrood passed the Gaelic Language Act in 2005, I was concerned that “official status” would mean scarce resources being devoted to largely pointless gestures, like translating official reports that nobody reads.

There is a legitimate debate (which also exists in Ireland) about whether the “numbers game” of expanding Gaelic-medium schools in cities is at the expense of prioritising communities where the language is in daily use but the thread of continuity is slender. That feeds into socio-economic issues in these places – for without people there is no language.

It should be possible to have these discussions about means not ends without them being turned into bogus controversies which invariably end up with the same dreary cliches, probably with the aid of radio phone-ins, about whether or not Gaelic “matters”.

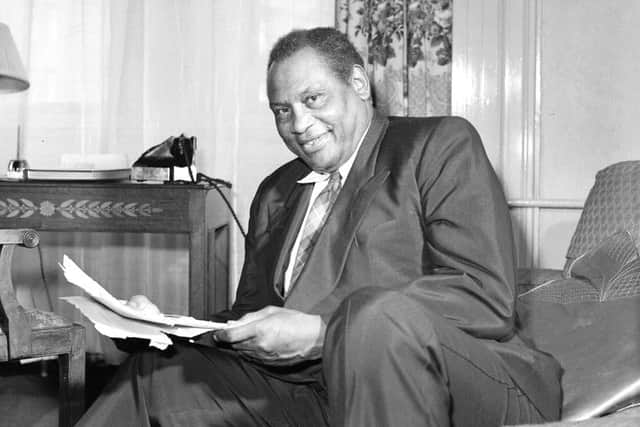

By chance, I came across a press report from 1960 when the great singer and political activist Paul Robeson visited Glasgow. He confirmed he had been “keeping up with his Gaelic studies and demonstrated his proficiency by reading a passage from one of his well-thumbed text-books”. Robeson added: “Hebridean songs are very important to me because they represent music built on a world language, the pentatonic scale, and in the world language they are among the most beautiful.”

Advertisement

Hide AdIt was one small reminder that in the Gaelic language and culture, Scotland has a priceless asset. Remarkably, it still stands a chance as a living language for generations to come. Let’s just get on with doing our best towards that outcome for the alternative would shame us deeply.