William Dalrymple on the Koh-i-Noor diamond, colonialism and Brexit

The document signed by the young maharaja handed over to a private corporation, the East India Company, great swathes of the richest land in India – land which until that moment had formed the independent Sikh kingdom of the Punjab. At the same time Duleep Singh was induced to hand over to Queen Victoria personally the single most valuable object not just in the Punjab but in the entire subcontinent: the celebrated Koh-i-Noor diamond, or Mountain of Light.

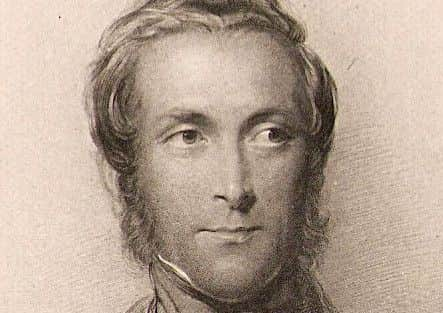

When he heard that Duleep Singh had finally signed the document, the Scottish Governor General, James Broun-Ramsay, Lord Dalhousie, was triumphant. “I have caught my hare,” he wrote. He later added: “The Koh-i-Noor has become in the lapse of ages a sort of historical emblem of the conquest of India. It has now found its proper resting place.”

Advertisement

Hide AdThe East India Company, the world’s first really global multinational, had grown over the course of a century from an operation employing only 35 permanent staff, headquartered in one small office in London, into the most powerful and heavily militarised corporation in history: its army by 1800 was twice the size of that of Britain. It had had its eyes on both the Punjab and the diamond for many years. Its chance finally came in 1839, at the death of Ranjit Singh, when the Punjab had quickly descended into anarchy. A violent power struggle, a suspected poisoning, several assassinations, a civil war and two British invasions later, the Company’s army finally defeated the Sikh Khalsa at the bloody battle of Gujrat on 21 February 1849.

At the end of the same year, on a cold, bleak day in December, Dalhousie arrived in person in Lahore to take formal delivery of his prize from the hands of Duleep Singh and his Scottish guardian, Dr Login. Still set in the armlet which Maharaja Ranjit Singh had worn, the Koh-i-Noor was removed from the safe of the Lahore Toshakhana, or Treasury, by Dr Login, and placed in a small bag which had been specially made by Lady Dalhousie. Broun-Ramsay wrote out a receipt: “I have received this day the Koh-i-Noor diamond.”

In Scotland we are good at remembering all we have suffered at the hands of English aggression and colonialism, but often forget all we contributed to British colonialism elsewhere – and nowhere more than in India. It is true that the Scots were slow starters in the field of Empire building. Early attempts to set up a Scottish East India Company in 1695 and found a colony at Darien three years later both proved humiliating failures. But by the end of the 18th century, the Scots were making up for lost time. If the Scots diaspora played a major role in Imperial projects from Vancouver to Mandalay, it was particularly in South Asia that they came to prominence. “It was India,” writes Linda Colley in Britons, “that the Scots made their own.”

Well connected but financially embarrassed Scots gentry queued up to take their chance in the great Indian lottery, flooding first into the East India Company, then into the successor institutions of the Victorian Raj and the wider Empire. “Would you suppose it?” wrote Aleck Fraser of Inverness from Delhi in 1811. “We usually sit down 16 or 18 at the Residency table, of whom nearly half, sometimes more, are always Scotchmen – about a quarter Irish, the rest English. The Irish do not always maintain their proportion – the Scotch seldom fail.” As the 19th century progressed, the Scots diaspora filled a disproportionate and ever-growing number of imperial positions across the globe.

For better or worse, the British Empire was the most important thing the Scottish ever did. It altered the course of international history, and shaped the modern world. It also led to the huge enrichment of Scotland, just as, conversely, it led to the impoverishment of much of the rest of the non-European world.

Yet much of the story of the Empire is still absent from our history curriculum. This means that most people who go through the current education system are wholly ill-equipped to judge either the good or the bad in what we Scots did to the rest of the world. This matters. Over and again, we see our diplomats, businessmen and politicians wrong-footed as they constantly underestimate the degree to which we are distrusted across the breadth of the globe, and in a few places actively disliked. Because of the wrong-headedly positive spin we tend to put on our Imperial past, we often misjudge how others see us, and habitually overplay our hand. For the fact is that the legacy of the Raj is something millions of Indians are still deeply uncomfortable about.

Advertisement

Hide AdThis was demonstrated most recently, and most humiliatingly, to Theresa May when she went to India with a delegation of businessmen this winter. Having fallen out with Europe over Brexit, she seemed to believe that she would be welcomed in India with open arms. Indeed the Prime Minister seemed to be under the arrogant impression that she could just kick-start the Empire, as if it was some sort of old motorbike which had been left in a garage for a few years and which now, given the breakdown of Britain’s European limousine, she could merrily mount and ride off into the sunset. But her strategy of trying to strike trade deals with Commonwealth countries – dubbed Empire 2.0 by some in the Civil Service – certainly turned out be difficult to sell in this former colony, which now casts much more loving looks towards America than it does towards us. In the end, May’s visit to India was a humiliating failure.

For the truth is that Indians have very bitter memories of British rule. Today it is believed in India – whether rightly or wrongly – that the British came as looters and plunderers, and subjected the country to centuries of humiliation. And it is certainly true that for all the irrigation projects and new railways, the Raj presided over the destruction of Indian political institutions and cultural self-confidence, while the economic figures speak for themselves. In 1600, when the East India Company was founded, Britain was generating 1.8 percent of the world’s GDP while India was producing 22.5 percent. By 1870, at the peak of the Raj, Britain was generating 9.1 percent, while India had been reduced to a poor third-world nation with just 12.2 percent, a symbol across the globe of famine and deprivation.

Advertisement

Hide AdLast year a video went viral in India of the eloquent Congress politician, Shashi Tharoor, arguing at the Oxford Union that Britain owed India reparations for the damage inflicted by the Empire: at last count, the YouTube video of his speech had five million views. It was instructive to watch the surprised reaction in Britain: hadn’t we given the Indians railways, cricket and democracy? On a Sunday morning BBC talk show it was even claimed that, unlike the Belgians, the British never committed any atrocities in the course of their Empire building. Tharoor was forced to remind his interlocutor of the Amritsar Massacre, where in the space of a single hour, according to official British figures, 379 civilians were killed and 1,200 injured when General Dyer’s troops opened fire on a crowd of unarmed protestors.

Tharoor could have come up with many much worse examples, for example the massive bloodshed in the aftermath of the Great Uprising of 1857, when the British army – including several Highland regiments – massacred many tens of thousands, perhaps hundreds of thousands, of innocents. Yet in Britain we remain largely ignorant of the blackest side of the imperial experience, and are still taught in school that it was only our German enemies who turned racism into an ideology that justified mass murder. In contrast the Raj, we like to believe, was like some enormous Merchant Ivory film writ large over the plains of Hindustan, all parasols and Simla tea parties, friendly elephants and handsome maharajahs.

The story of the Koh-i-Noor, a symbol of the sovereignty of India, taken from South Asia by force under the watch of a Scottish Governor General, raises not only important historical issues, but contemporary ones too, being in many ways a touchstone and lightning rod for attitudes towards colonialism and posing the question: what is the proper response to imperial looting? Do we simply shrug it off as part of the rough-and-tumble of history or should we attempt to right the wrongs of the past? It is certainly something we all should think over carefully, not least given the importance of good relations with India – arguably among the most important trading partners that Scotland has in a post-Brexit world – in the coming Asian century.

*Koh-i-Noor: The History Of The World’s Most Infamous Diamond by William Dalrymple and Anita Anand is published this week by Bloomsbury, £14.99