When a murderous doctor met Edinburgh’s real-life Sherlock Holmes

One of the most prolific serial killers of the Victorian Age – a monster who would become known as London’s “Lambeth Poisoner” – arrived in Edinburgh in April 1878. He had already murdered one woman and as many as nine more people would die at his hands. But Thomas Neill Cream had come to the Scottish capital in search of a medical licence, not victims. And he was about to come face-to-face with a real-life Sherlock Holmes.

Three times each year, Edinburgh’s medical certification bodies – the Royal College of Physicians and the Royal College of Surgeons – joined forces to examine candidates. Doctors flocked to the city, hoping to obtain a coveted license to practice both medicine and surgery. “Much trouble is saved to the candidate,” noted a study of medical education in Britain in the 1870s, “by having to present himself at one board of examiners only.”

Advertisement

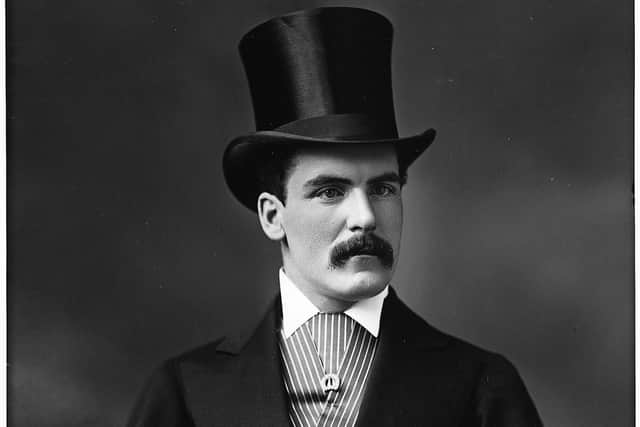

Hide AdCream, the 27-year-old son of a wealthy timber merchant in Quebec City, had graduated from McGill Medical School in Montreal in 1876. He looked the part of the Victorian gentleman, complete with bushy mustache and black top hat. A family friend regarded him as “a young man of rare ability” who was “destined to make his mark in the world.” And he would, but not in the way those who knew him expected.

His life had begun to slide off the rails soon after his graduation. When his fiancée, a young Quebec woman named Flora Brooks, became pregnant, he performed an abortion. Brooks barely survived the procedure and Cream was forced to marry her. He quickly fled to England, but stayed in touch with his bride and sent her medicine that seemed to hasten her death in 1877, at age 24. Her family doctor suspected she had been poisoned but failed to alert the authorities.

Cream spent the next year completing post-graduate training at St. Thomas’ Hospital in London, only to fail the examinations required to obtain a license from England’s Royal College of Surgeons. So he journeyed north, a trip that was also a homecoming. He had been born near Glasgow and his family had emigrated to Canada when he was four.

He faced two rounds of written examinations in Edinburgh. Candidates were also required to perform surgical procedures on cadavers and visit hospitals, to examine patients and diagnose their illnesses. The final step was an appearance before a panel of medical experts for further evaluation and questioning.

The drawn-out assessment process kept Cream in Edinburgh for at least two weeks. At some point he may have met or encountered Arthur Conan Doyle – the future author was completing his second year of studies at Edinburgh’s medical school and was in the city for most of April. Cream did, however, come face-to-face with Conan Doyle’s favourite medical school instructor and one of Edinburgh’s most renowned physicians.

Dr Joseph Bell was secretary-treasurer of Edinburgh’s Royal College of Surgeons, and Cream and other candidates were directed to his home at 20 Melville Street to submit their educational and training records and to pay examination fees. Bell taught surgery and amazed his students with his ability to size-up patients – a crucial skill for doctors in an era when a diagnosis was often based on little more than a person’s appearance and visible symptoms. But he seemed to be able to read minds as well. Within seconds of meeting new patients, based on their clothing, accents, and other clues, he could correctly identify where they had been born, where they lived, what they did for a living, and other personal details.

Advertisement

Hide AdConan Doyle, who worked as Bell’s assistant during his student days, was in awe. “His intuitive powers,” he recalled, “were simply marvellous.” Years later, when he longed to abandon medicine for a writing career and was looking for a model for a fictional detective, Conan Doyle would remember Bell’s amazing powers of observation, how he used logic and evidence to make lightning-fast deductions. And in that instant, Sherlock Holmes would be born.

The Edinburgh examinations began on 2 April. One in three candidates failed to get through this initial round in 1878, but Cream passed. In mid-April he appeared before six examiners for more questioning. Bell was among the representatives of the College of Surgeons on the panel.

Advertisement

Hide AdThe president of the College of Surgeons, Dr Patrick Heron Watson – a possible model for Holmes’ crime-solving partner – signed off on the final panel’s finding that Cream had been “found duly qualified to practice.” The double qualification, noted a medical expert of the time, “should entitle its holder to practice all branches of the profession in any part of Her Majesty’s dominions.”

Cream returned to Canada with his prestigious license. He continued to perform illegal abortions and callously decided some of the women who sought him out, desperate to end unwanted pregnancies, would die. He poisoned a patient in Ontario and fled to Chicago, where he murdered three more young women. His weapon of choice was a lethal dose of strychnine added to medicine he provided. He was convicted of murder in 1881 for poisoning his lover’s husband and served ten years of a life sentence before being released from an Illinois prison. He immediately returned to London, where he poisoned four prostitutes in the Lambeth neighbourhood before Scotland Yard detectives arrested him in 1892.

When Bell encountered Cream in Edinburgh in the spring of 1878, he had plenty of time to size up the doctor from Canada, to glean information from his mannerisms and his appearance, to search for clues as he had done so often to the astonishment of his students. Cream never lost his Scottish accent, and Bell would have found it easy to pinpoint his Glasgow origins. From Cream’s expensive clothes he may have deduced – correctly – that this scion of a wealthy family, sent overseas to burnish his medical credentials, was vain, self-absorbed, and spoiled.

But not even Joseph Bell, for all his superhuman ability to observe and deduce, had sensed the evil lurking within Thomas Neill Cream.

The Case of the Murderous Dr Cream: The Hunt for a Victorian Era Serial Killer, by Dean Jobb, is published in the UK by Algonquin Books on 17 August, and is available to pre-order now. Jobb is an award-winning true crime writer who teaches in the MFA in Creative Nonfiction program at the University of King’s College in Halifax, Nova Scotia. His website is www.deanjobb.com

A message from the Editor:

Thank you for reading this article. We're more reliant on your support than ever as the shift in consumer habits brought about by coronavirus impacts our advertisers.

If you haven't already, please consider supporting our trusted, fact-checked journalism by taking out a digital subscription at https://www.scotsman.com/subscriptions