Stuart Kelly's Wigtown Book Festival Diary

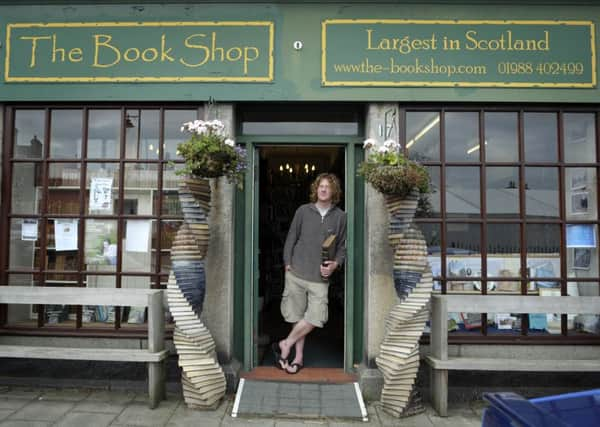

On the opening night, Wigtown stalwart Shaun Bythell, whose bookshop doubles as the Writers’ Retreat for the duration, was centre-stage rather than beavering away on the sidelines, for the launch of his book The Diary Of A Bookseller. I can confirm that all the parts about me in it are true. It’s a work which is both laugh-out-loud funny and chin-strokingly ponderous. On stage, he talked about the tiny indicators of how the economy is doing from the perspective of the second-hand book trade – the difference, for example, for when fivers rather than tenners became the standard denomination. Bookselling has, of course, gone through its own revolution with the rise of Amazon, about which Bythell’s opinions are stark and unprintable. Three particular revolutionary periods received particular attention. Firstly, there were several events about the 500th anniversary of Martin Luther nailing his 95 Theses to the door of Wittenberg Cathedral. As both Alec Ryrie and Peter Marshall showed, in different ways, an event that probably never happened of a text that nobody nowadays reads, has fundamentally formed the modern world.

Other events focused on the “decade of revolution” in the 1790s, with Rachel Hewitt giving a provocative talk on the invention of emotion in the period – the idea that emotions are in a kind of circulatory system, so all those metaphors of boiling up, spilling over, flooding out and so forth. Mike Rapport looked at the same period in a more bricks and mortar way, analysing how the architecture and planning of the city itself contributed to radical insurrection, in London, Paris and New York.

Advertisement

Hide AdAngus Roxburgh’s memoir about his time in Russia showed, chillingly, why Russia seems so shy at commemorating the 1917 October Revolution, as the state’s grip tightens again. There were also failed rebellions, with the historians Jacqueline Riding and Sarah Fraser giving a spry counterfactual fantasia on what would have happened if Bonny Prince Charlie had actually won.

The novelist and comedian Natalie Haynes performed a bravura hour, “Stand Up For The Classics”, where she deployed her formidable wit to encourage the audience to appreciate the work of Sophocles in particular. She riffed on an ingenious analogy between the soap opera and Aristotle’s rules for tragedy.

Julian Glover gave one of the best talks I have heard at a book festival on Thomas Telford, a salutary reminder that some revolutions are about building roads, not barricades. It should be released online as a model of how to engage with audiences.

Passing by the local pub, I heard a string quartet playing – Kirsty Main, Gillian Grant, Sam Watkin and Balázs Renczés, the Cairn String Quartet – and popped in to sit entranced, even at a witty rendition of a Proclaimers song. Sometimes the revolutionary is the delightfully unexpected.