Stuart Kelly: Who was the real Martin Luther?

Martin Luther: Renegade And Prophet by Lyndal Roper | Bodley Head, £25

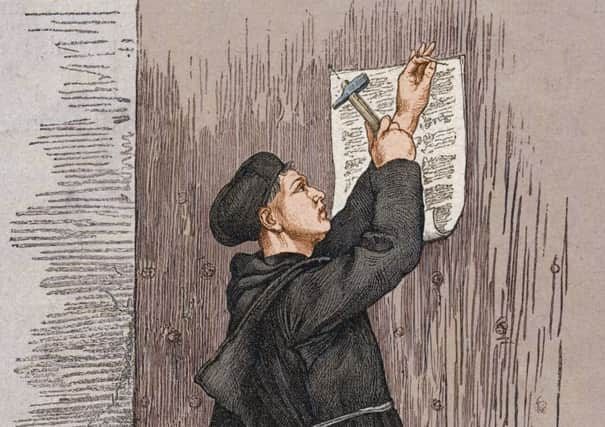

Martin Luther, whose Ninety-Five Theses, nailed – or glued – to the door of Wittenberg Castle Church on Halloween 1517 supposedly sparking the Reformation that would split Western Christianity, is a dream and a nightmare for a biographer.

Advertisement

Hide AdThe earliest sources are hagiographies where he is Christ-like, or vituperative denunciations where he is positively Satanic. Later writers have seen him as a radical liberator, allowing the common people to read the Bible in their own language and curtailing abuses within the church, or as a compromised conservative, who denounced the Peasants’ Revolt and spent most of his time fighting backsliding allies over abstruse points in theology rather than his supposed and actual enemies.

Worse than the contradictions is the determination of a tipping point. In some ways I would love to see a biography of Luther that just consisted of portraits of him; that allowed the reader to chart the changes: how did the ascetic young monk become the corpulent patriarch? Biographies of Luther are all about change. When did he decide to break with his monastic vocation? When did he decide to become a monk anyway? When did the principled priest who later traditions claim stood at the Diet of Worms before his religious and secular masters and said “Here I stand, I can do no other” become the temporiser who advised the aristocracy on the best way to get away with bigamy? When did reforming the Church turn into creating his own Church?

Lyndal Roper’s extensive and engaging biography flirts with all these problems, and is cautious about giving neat answers to complex questions. Roper’s chief aim is to write a biography of Luther the human being, not Luther the theologian or Luther the legend; and doing so allows her to admit the flaws – and they were legion – as well as recognise the virtues – and they were considerable.

Perhaps Luther himself is to blame that so many writers about him reach for the nearest copy of Freud. His language, particularly latterly, is so unremitting in its references to dung, urine, excrement and vomit that one wonders why. Roper’s answer is that Luther somehow became “comfortable” with the body – humanity is basically a mess, and the mess of the lavatory or the bedroom is at least more honest than the psychic mess of envy or pride. But despite his own jovial or plaintive correspondence to his friends about his piles or constipation, the use of such language against opponents still strikes a jarring note.

Likewise, the biography shades into the psychoanalytical in looking at Luther rejecting first his father, then his spiritual father, Johann von Staupitz, then the Pope. At which point, after a period in hiding, he became a father, and something of an autocrat. In a way, it seems as if Luther never got over not being a martyr. His resolution to speak out, and resolution to die for his beliefs, was both genuine and inspiring. The later letters to friends, and the later comments on submitting to secular authorities, keep harping on about the necessity of being prepared to be killed if need be. In this respect he is very like John Knox, who was utterly prepared to sacrifice himself and yet never was called to do so. Both Knox and Luther changed radically, not after being convinced they might die, but in the aftermath of not dying.

Roper’s biography is very strong on the economic background and how it translates into spiritual questions. The Reformation came about at the same time as capitalism emerged out of feudalism, and it both reflects and reprimands the structures. Luther raged against the idea of a kind of heavenly bank whereby good deeds or indulgences gave you credit with God; just at the same time as the Fuggers were creating modern banking. That he grew up in a mining town, rather than an agricultural community, gives pause for further thought. Luther was technological before he began printing his sermons.

Advertisement

Hide AdAlmost every page of this book has a fact that made me gasp. The overall theory of the work might be to be careful about grand stories, but the individual nuggets are like miniature epics in their own right. Take, for example, the idea that Frederick III, who protected Luther at a key moment, had a personal collection of 19,013 saintly artefacts and 117 reliquaries, which included a twig from the burning bush Moses saw and a vial of the Virgin’s breast milk. The church that housed them now has a death mask of Luther. Or that Luther seemed to believe that the precise interpretation of Jewish texts had been facilitated by early Jews having drunk the urine and eaten the faeces of the dead Judas. I shudder at how that has rippled down the centuries.

We cannot truly imagine how these people thought, but their thought influenced everyone. This book brings clarity to how complicated, strange, ennobling and disgusting the period was.