There, perched among the marram grass, were three unusual estuarine lighthouses; Drogheda North, East and West lights were truncated structures that stood like daleks on stilts, gazing forlornly out to sea and only coming to life as the dusk crept in.

The sense of solace and reassurance that I felt in the warm glow of those beacons as they illuminated those summer nights was an almost tactile experience that has remained with me ever since.

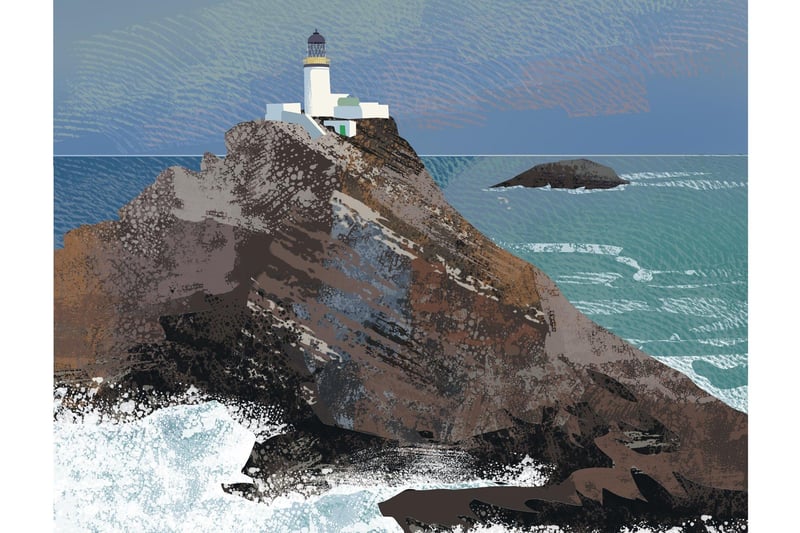

Early in 2017, inspired by the railway posters of the 30s and 40ss, I started illustrating some of the lighthouses along Ireland’s south coast. This quickly grew into a collection that culminated in an award-winning book “Lighthouses of Ireland”.

During this time, I spent a holiday in Cornwall which spurred me to consider painting some of the lighthouses on the Cornish and Devon coasts. Before you knew it, I was poring over maps from Somerset to Scotland.

The collection now runs to over 350 lighthouses and a selection of these will appear in my new book “Lighthouses of Britain and the Isles” which will be published by Watkins in the spring of 2024. The collection is not by any means complete, but bit by bit the missing pieces will be added, creating a comprehensive compilation of our best loved sentinels and beacons.Scotland has some of the most interesting and ground-breaking lighthouses thanks in large part to the genius of three generations of the Stevenson engineering family, and in general these sentinels are set in breath-taking and spectacular settings.

17 Inspiring Quotes about Scotland from famous folk starting with Sam Heughan from Outlander

The western shores and islands in particular are full of drama, with their shorelines and cliffs exposed to the brunt of the wild Atlantic waves. Further east is the infamous Pentland Firth where the Atlantic channels into the North sea create ferocious currents and tides with monikers such as the Swilkie, the Bore of Huna, the Wells of Tuftalie, the Duncansby Bore, and the Merry Men of May.

Despite their charming names, these currents have caused havoc at sea and inspired some of the most iconic lighthouses such as Stroma, Dunnet Head and the Pentland Skerries to safely guide vessels past these hazards to shipping.

At the northern extremity of Scotland, Muckle Flugga still clings to its perch despite being regularly inundated by the waves, while the southernmost lighthouse in the care of the Northern Lighthouse Board isn’t in fact in Scotland at all, but is rather, Chicken Rock, off the south coast of the Isle of Man. (The Mull of Galloway claims the title of Scotland’s most southerly sentinel).

I’m often asked which my favourite lighthouses are and it’s like being asked your favourite scotch whisky. It’s not so much that you don’t have favourites, rather that it’s such a shame not to give the others a try. That said, Bell Rock and Skerryvore are up there for daring and engineering brilliance. The Isle of May makes the cut for endurance and Neist Point for sheer beauty and drama.

If you want to explore the legacy of Scottish lighthouses, there’s probably no better place to start than Bell Rock, 11 miles off the Angus coast at Arbroath. It’s the oldest rock lighthouse in Britain and exemplifies the engineering finesse and elegance that the Stevenson family became famous for.

The name is reputed to have originated when the 14th century Abbot of Aberbrothock, sailed out and fitted a device containing a wave activated warning bell on the rocks. Whether it worked or not is unknown, but legend has it that the bell lasted only a year before a Dutch pirate by the name of Ralph the Rover stole it, only to founder like a pantomime villain on the self-same rocks 12 months later.

On the west coast, the Lighthouses are even more Isolated. During the build of Ardnamurchan, the work site was so far from supplies of fresh food that the builders came down with scurvy and fruit, vegetables (and a doctor) had to be hastily brought to the station.

At least they were on dry land. On numerous occasions during fierce winter storms, lighthouses such as Sule Skerry (the most isolated lighthouse in Scotland) were cut off for weeks on end by heavy seas, preventing any landing and the keepers had to make their rations stretch until the weather improved and a relief boat could reach them.

The job of bringing supplies to a rock station were complicated by weather and accessibility. On a blustery winter’s evening, climbing the greasy metal rungs of Dubh Artach or Skerryvore laden with sacks of provisions having hoisted up the heavier material must have been hair-raising to say the least.

Storms could spell disaster, but they could also bring small rewards. Engineer Alan Stevenson noted that on the west coast of Tiree, the crofts on the storm washed shore rented for slightly more than on the leeward side because of the plethora of wreck that washed up on that side. Indeed, locals were often opposed to the establishing of lighthouses because of the reduction they would see in bounty if shipwrecks were avoided.

Perhaps the most impressive of the western lighthouses is the imposing Skerryvore, probably Alan Stevenson’s crowning achievement. Having spent a season preparing foundations and a base camp on the rock, the crew returned the following year to find that everything had been washed away. Undaunted, they started again and soon were laying 85 enormous blocks of granite a day. At 158 feet, it’s the tallest in Scotland.

Lighthouses have been the source of tales of derring-do and ingenuity, but also of tragedy, such as the one associated with Kinnaird Head, now the Museum of Scottish Lighthouses, where Isobel, the daughter of the 8th Lord of Philorth having thrown herself to her doom, is reputed to haunt the shoreline during stormy weather, while the pipes of her drowned lover provide an eerie soundtrack.

There’s also the wild and stormy Flannan Isles, where on December 26th 1900, three lightkeepers mysteriously disappeared creating a century of speculation. Sometimes the stories are simple tales of romance between the an assistant keeper and a local girl with an eye for a sharp uniform.

While at their core, these structures are simply towers and beacons, our lighthouses have captured the imagination in a way that few other buildings have.

Maybe it's the idea of strength and resilience, a guiding light in the darkness, that feels so relevant in our challenging times. Perhaps it's just a childlike fascination with tall towers and spiral staircases, but everyone seems to have a favourite. The lighthouse represents a unique part of our maritime history and an aesthetically pleasing part of our built heritage. Long may they continue to shine.

All images are available as prints at LighthouseEditions.com and will be the subject of a beautiful book of prints and stories which will go on sale in 2024.

Subscribe

Subscribe at www.scotsman.com/subscriptions

1. stts-00-04-23-lighthouses high res-dunnet head.JPG

Easter Head, Caithness lighthouse Photo: hy

2. stts-00-04-23-lighthouses high res-muckle flugga.JPG

Muckle Flugga lighthouse Photo: hy