Sir Walter Scott at 250: National treasure or "sham bard"?

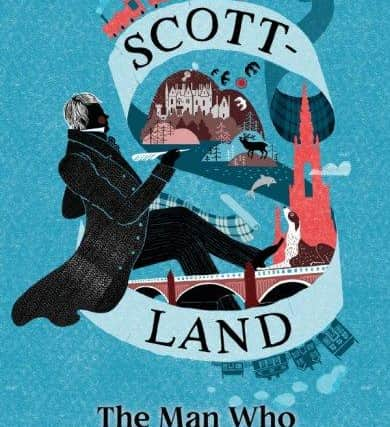

Poor, poor Sir Walter Scott. Ever since his death he has been reassessed. It wouldn’t be an exaggeration to say he has been reassessed to death, and I am in part guilty of the crime, with my book Scott-Land: The Man Who Invented A Nation. The subtitle certainly tweaked a few nerves, but I stand by it. So, in the past 250 years we have had the Scott of whom Lord Cockburn said “to no other man does Scotland owe so great a debt of gratitude as to Walter Scott” and the Scott who was to Edwin Muir “the sham bard of a sham nation”. He is seen as a strategic patriot – especially, and it is always good advice not to go toe-to-toe with an Edinburgh lawyer – when he defended the right of Scottish banks to print their own notes against a proposal from Westminster, pointing out that it broke the 1707 Act of Union. He is seen as a British stooge, parading George IV around Edinburgh in grabs and jewels that would not shame a Kardashian. He inspired Pushkin, Dumas and Tolstoy and was loathed by Mark Twain, Emile Zola and EM Forster.

He is an immense paradox. How could somebody be so precise in his accounts and so profligate in his spending? How could he be unassuming and the most famous writer in the world (the second work, after the Bible, translated into Iroquois was by Scott)? How did he negotiate his salvage operation on Scottish culture with The Minstrelsy Of The Scottish Border and so much more and his commitment to a new “North Britain”? How did the young man who seemed enthusiastic at the first actions of the French Revolution end up writing a biography of Napoleon? Scott was an aristocrat beloved by Communist literary critics, and a reactionary progressive. He is as much of a puzzle as his “Conundrum Castle”, as he called it, of Abbotsford.

Advertisement

Hide AdThe answer to a complicated set of questions should be complex, so I will offer no easy answers, only indications of why Scott is still relevant. Since Scott was a lawyer and “the Shirra’” of Selkirk as well as a novelist, let us proceed in a legal fashion.

Case for the prosecution: Scott is longwinded, boring and a bit of a fuddy duddy.

Case for the defence: There might a sliver of truth here, and I will merrily give you £50 sterling if you can quote the opening sentence of Castle Dangerous from memory. But may I ask my learned friend, have you read Richardson’s Sir Charles Grandison or Fielding’s Amelia?

Case for the prosecution: M’lud, but Scott is difficult.

Case for the defence: Have you read Finnegans Wake? I will accept the minor charge of being somewhat ramshackle, but part of the glory of this work is that satire, swashbuckling, poignancy, insight and analysis sit side-by-side, just in a similar manner to how the Russian critic Bahktin described Dostoyevsky as being like a newspaper, with tragedy and banality and comedy all on the same page.

Case for the prosecution: Scott traduced Scotland and reduced it to a shortbread tin.

Case for the defence: Demonstrably false. Shortbread was first recorded in the 12th century and it was only with the entrepreneur and baker, Joseph Walker, in 1898 that the vogue appeared. The tins owe more to the painter Sir Edwin Landseer than to any work of my client. There is no record of him even eating shortbread, let alone wearing a kilt.

Case for the prosecution: Scott was a Tory snob.

Advertisement

Hide AdCase for the defence: He was a Tory, as was James Hogg, the so-called Ettrick Shepherd, who is much beloved by the supposedly progressive writers of today. Nevertheless, his view of history was decidedly Whiggish, before Lord Macaulay invented the idea of history being a gradual amelioration, a careful crafting of things to be better, and before Hegel’s idea that history progressed by a thesis and an antithesis clashing to creating a synthesis. What better description of these novels where Normans and Saxons bring about England, where Roundheads and Cavaliers find common ground, where Jacobites and Hanoverians end up in a marriage?

Judge: bring the prisoner before the bar. Mr – sorry - Sir Walter, I find you a very amiable chap indeed and all cases are henceforth and in perpetuity dismissed.

Advertisement

Hide AdI do not say all that in jest. Scott is not just an amiable writer, but a very humane writer. It would not be an understatement to call him one of the first writers with a sensitivity to the idea of multiculturalism. Across his novels he depicts Jewish characters (in Ivanhoe), Muslim characters (in The Talisman), Hindu characters (in The Surgeon’s Daughter) and gypsy characters (in The Heart of Midlothian). You only need to compare Isaac of York in Ivanhoe with Fagin in Oliver Twist to see how Scott was ahead of his time, not behind the times. Scott had a love for the renegade, the rascal and the radical, those who found themselves, ironically, on the wrong side of history. The only people he satirises are people like him, lawyers and antiquarians. If I have a favourite scene in all the novels it comes from The Antiquary, where the two caricatures are arguing over whether a ditch is Roman or Pictish. An old vagrant passes by and recalls when he dug said ditch, leaving both dumbfoonert.

Scott is not trapped in aspic; he was a man between the past and the future. I have always thought that Scott did not want to be a novelist, but his polio in infancy prevented him being what he wanted to be: a soldier. The treatment for his affliction reflects this. On one hand, his family have him treated by the most innovative and crazy medical practitioner of the day, James Graham, the “Emperor of Quacks”, who tried to heal him with galvanic shocks. Scott’s mother’s family were part of Edinburgh’s enlightened medical establishment. When that did not work, he is sent to his father’s family in Smailholm, where his leg is wrapped in a lamb’s caul and where his nursemaid tries to kill him with a pair of scissors. The Gothic and the Enlightened were always entwined in Scott.

He was also strangely prescient. Many people skip the prefaces, but they are where Scott is at his most witty, where me meet characters like Captain Clutterbuck, who tells one of the shaggiest of shaggy dog stories, the historian Mr Drydasdust and various iterations of the mysterious “Author of Waverley”, as the Eidolon, a shadow, the preses of a collective of authors: “It is, indeed, to me a mystery, how the sharp-sighted could suppose so huge a mass of sense and nonsense, jest and earnest, serious and pathetic, good, bad, and indifferent, amounting to scores of volumes, could be the work of one hand, when we know the doctrine so well down by the immortal Adam Smith, concerning the division of labour”. He goes on to claim that the villain of The Antiquary, Dousterswivel, has invented a novel-writing mechanical loom, which takes the effort out of describing female characters and coming up with moral conclusions. “The Wizard of the North” was also conjuring the Internet.

Let us not reassess Scott again. Let’s instead just read him. He might well surprise you.

Stuart Kelly is chief literary critic of Scotland on Sunday. His book Scott:Land: The Man Who Invented a Nation is published by Polygon, price £12.99. For more information on this year’s #WalterScott250 celebrations, visit https://walterscott250.com/

A message from the Editor:

Thank you for reading this article. We're more reliant on your support than ever as the shift in consumer habits brought about by coronavirus impacts our advertisers.

If you haven't already, please consider supporting our trusted, fact-checked journalism by taking out a digital subscription at https://www.scotsman.com/subscriptions