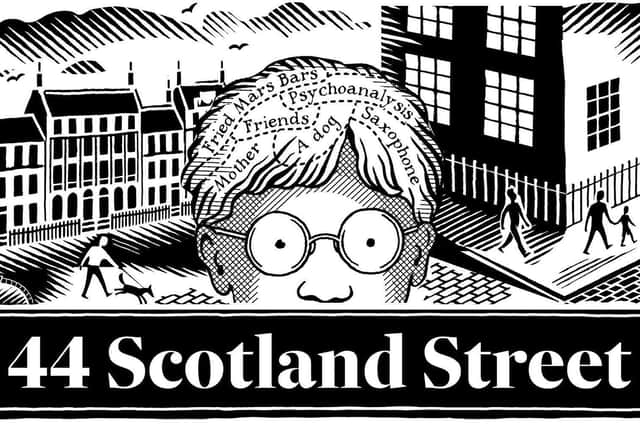

Scotland Street Volume 17, Chapter 51: An Authentic Voice

Ben nodded. “A perfectly reasonable question,” he said. “What did Mallory say about Everest when they asked him why he climbed it? Because it’s there. Isn’t that what he said?”

Donald smiled. “So you’re interested in the Picts because they’re there?”

Advertisement

Hide Ad“Were there,” said Ben. “They’re not there any longer. Ergo were there. There’s a certain fascination in things that have simply disappeared. And that applies to the Picts. We know that they existed – the Romans were aware of them, and indeed gave them their name – ‘painted people’. But what do we know about them? Very little.” He paused. “Of course, we know that they painted their faces, which some of their descendants still do. Have you been to a rugby match at Murrayfield recently? You see quite a few people there with their faces painted blue. And political rallies too. A lot of blue facepaint in evidence on such occasions.”

Bruce gave a dismissive laugh. “Is there something vaguely sinister about that?” he asked. “Why paint your face blue? To intimidate the opposition? To protest your membership of the group?”

Donald shrugged. “Flags come into it, I imagine. Political rallies involve the waving of flags. Flags encourage enthusiasm for the cause – whatever the cause may be. But let’s not get too involved in the psychology of political attachment. Let’s return to the Picts. You’d argue, I take it, that what makes the Picts of interest is their mystery. What intrigues people is the fact that we don’t know how the Picts led their lives. What did they believe in, before they became Christian? Who were their gods? What did they eat? We don’t really know what language they spoke – although there have always been theories about that.”

“Gaelic?” said Ben. “That’s what we were taught at school back in the day.” He turned to address Bruce, “Remember Mr Stoddart, Bruce? Remember his history lessons? He had latched onto the idea that the Picts spoke a non-Indo-European language. He used to say that there was a great deal of evidence to that effect, but when you asked him what the evidence was, he simply closed his eyes and shook his head. We laughed at him, and I think he knew that. Teenagers are cruel, especially when they sense blood.”

Bruce remembered. “Yes,” he said. For a few moments he was silent. I have been so wrong, he thought – so wrong about everything. But at least I am being given a chance to be better, which not everyone gets. I should be grateful for that.

They had given Donald a photograph of the inscriptions etched into the surface of the stone tablet. He now reached for this and pointed to the symbols that ran across the base. “This is ogham,” he said. “You’ll know that, of course. It’s a very old script.”

Ben nodded. “We were hoping you’d translate it for us.”

Advertisement

Hide AdDonald sighed. “It’s not always easy to decipher. We’re learning more and more about it, but many of these early inscriptions are somewhat opaque, I’m afraid. Often they’re simple lists – so-and-so owes a local potentate two cattle, or something of that sort. Early laundry lists, in some cases.”

“Every society needs its records,” said Ben. “They meant something, I suppose. But eventually they started to tell stories.”

Advertisement

Hide Ad“Precisely,” said Donald. “And then literature begins.” He looked at the photograph with admiration. “And do you know what I think this is? I think this might be the very first work of Scottish literature – ever.”

For a few minutes nobody spoke. Then Ben said, “Even earlier than ‘The Brus’?”

“Oh, much earlier than that,” said Donald. “‘The Brus’ was written in the middle of the fourteenth century. That’s yesterday, really. This is earlier even than ‘The Gododdin’, which dates back to the second half of the sixth century.”

“I thought that was Welsh,” said Ben.

“They spoke Welsh in the Lothians,” said Donald. “The boundaries between the various kingdoms were fluid. ‘The Gododdin’ is definitely a work of Scottish literature in the geographical sense. But this is earlier than that. I think that this dates to the fourth century.”

“Amazing,” said Bruce. “And do you know what it means?”

Donald looked thoughtful. “I’m getting there,” he said. “I’d like to have a few more weeks to give it further consideration. It doesn’t do to commit to a meaning too early. But what I can say is that I think this is a poem – in fact I’m sure it is.”

This suited Ben. “It will be such wonderful publicity,” he said. “For our Pictish Experience Centre, that is. We can have a press conference to announce the discovery. We can get Creative Scotland on board.”

Advertisement

Hide AdDonald nodded. “The content is interesting,” he said. “It feels that there’s an entirely authentic voice speaking to us across the centuries.”

“Authentic?” said Ben.

“Very Scottish,” said Donald.

“Very exciting,” remarked Ben.

They spent another half-hour in conversation with Donald before saying goodbye. Then they walked together down Morningside Road. Ben wanted to call in on the cheese shop, where he chose a cheese for Catriona.

“A Mull cheddar,” he said. “She likes that sort of thing.”

Advertisement

Hide AdHe pointed to a small slice of cheese on the edge of the counter. “That’s a rather unusual cheese,” he said. “It’s made in Orkney, in very small quantities. The woman who makes it has only one cow, I’m told.”

Bruce looked at the cheese. He was tempted to buy the single slice on display, but resisted the temptation. It seemed almost indecent, he thought, to buy an entire production of anything. So he bought a small quantity of a powerful-smelling French soft cheese and then they resumed their journey.

“What do you think people like the Saltire Society will say about our discovery?” Bruce asked.

Ben was in no doubt about that. “They’ll be thrilled,” he said. “And why wouldn’t they? They want Scottish letters to flourish.”

“But what if it’s inappropriate?” asked Bruce. “What if it says the wrong thing?”

Ben hesitated before he replied. “Nobody’s going to judge it outside its historical context.”

Advertisement

Hide Ad“Let’s hope not,” said Bruce. “But perhaps we should not be too sure about that. There are plenty of people who are only too happy to judge the works of the past by the standards of today.”

“We can always publish it with a warning,” said Ben. “That’s the way most things are published these days.”

Advertisement

Hide AdBruce thought about the cheese he had just purchased. There were some cheeses, he believed, that should be sold only with an olfactory warning. This was not yet the case, but he was sure that such warnings would soon become standard practice.

© Alexander McCall Smith, 2023. The Stellar Debut of Galactica MacFee, published by Polygon, price £17.99, is on sale now. The author welcomes comments from readers and can be contacted on [email protected]