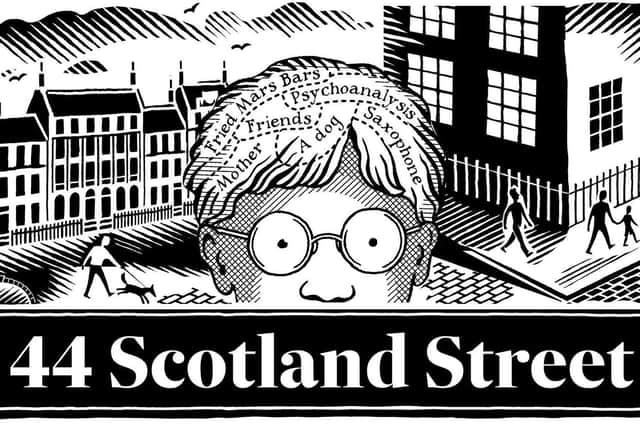

Scotland Street Volume 15, Chapter 8: Students eat anything

“I loved that sauce,” said Angus. “Delicious.”

Elspeth pointed towards the kitchen. “I told you: James is a superb cook. He can do anything, that boy. He could probably get a job at Prestonfield or Gleneagles. Anywhere, really.”

“I went to Prestonfield a few months ago,” said Matthew. “A client took me for lunch. He wanted to talk about buying a Peploe that had come up at auction. We had a wonderful lunch. There were peacocks strutting around on the lawns, people getting married in the marquee. We didn’t finish lunch until four o’clock. We’d paid no attention to the time.”

Advertisement

Hide Ad“Sometimes time does that, doesn’t it?” said Elspeth. “It forgets to whisper in your ear.”

Angus looked down at his plate. “That sauce – it was superb. It makes me want to lick the plate. Just to get the last drop of it.”

“Please do,” said Elspeth. “We’re not formal here.”

Angus smiled. “I sometimes do that at home. In fact, I often do.”

Domenica gave a look of mock disapproval. “He does, believe it or not. Most people stop doing that when they’re about ten.” She paused. “I’ve always assumed that he picked it up from his dog, Cyril.”

Angus defended himself. “I don’t see what’s wrong with it.” He gave Domenica a reproachful look. “We all have little things we do when nobody else is looking – harmless little habits that we wouldn’t want anybody else to see.”

There was a sudden silence at the table, as they each contemplated the truth of what had been said. Matthew blushed. Angus noticed, and wondered what it was that Matthew did, the mere thought of which caused embarrassment. Did he lick the plate too, or was it something worse – not that there was anything wrong in licking the plate. It was mere social custom that dictated that you should not do it. But waste not, want not: why not enjoy every last morsel rather than put the scraps in the food-waste bin?

Advertisement

Hide AdIt was as if Elspeth had read Angus’s thoughts. “I caught Matthew going through the food-waste bin the other day,” she said. “He takes out scraps and eats them. I caught him.”

All eyes turned to Matthew, who blushed again. So that was it, thought Angus. It was nothing to be ashamed of – nothing involving something that could not be talked about at the dinner table. Mind you, he thought, was there anything that could not be talked about at the dinner table today?

Advertisement

Hide AdDomenica laughed, perhaps slightly nervously. “I can understand that,” she said. “We throw away far too much.”

“But it’s not the purpose of the recycling bin,” said Elspeth. “The council collects scraps for a purpose.”

“I’ve often wondered what they do with the scraps,” said Angus. “You can’t feed swill to pigs these days, can you? They don’t want the wrong things getting into the animal food chain.” He paused. “Somebody said that they took it off somewhere and reprocessed it as food for students.”

“I doubt it,” said Elspeth. “If you can’t feed it to pigs, then should you be able to feed it to students?”

“Students eat anything,” said Domenica. “And drink anything as well. They are utterly undiscriminating.”

James reappeared with the next course – the rolled saddle of lamb. Matthew wanted to carve it at the table, which he now did, observing as he did so the perfection of the meat.

Advertisement

Hide Ad“This comes from just up the road,” he said. “From Baddinsgill. Local produce.”

James served the vegetables.

“Will you cook for us forever?” asked Domenica.

James smiled. But Domenica thought: I really would like things to be forever. I would like to be able to sit at this table once a week, perhaps, with these friends. I would like to talk about the things we talk about, the small things, whatever happened in the world. I would like to wake up in the morning and not think that things were getting worse. I would like not to have to listen to the exchange of insults between politicians. I would like to hear of people co-operating with one another and helping others and bringing succour and comfort to the needy and …and I would like not to think that we were not still in the seventeenth century here in Scotland, as divided amongst ourselves as they were at that time, pitted against each other, with one vision of the good battling another, and people despising others for their opinions. If only we could put that behind us and …”

She sighed.

“You sighed,” said Elspeth.

Advertisement

Hide Ad“Yes, you did,” said Angus, his mouth half full. “Or were you just breathing?”

“I was thinking of the seventeenth century,” said Domenica. “I was thinking of what it was like to live in Scotland in those days.”

“Unpleasant,” said Matthew. “No antibiotics. No anaesthetics. Unremitting toil. Religious extremism. No midge repellent, if you lived in the Highlands.”

“It was the religious extremism that was worst,” Angus suggested. “And the plotting of the various factions. Those ghastly nobles.”

“Have we changed all that much?” asked Domenica. “I mean, obviously things are better in some respects. People have rights; they have freedoms. We don’t have public executions. We aren’t forced to profess a particular religion.”

“Oh, that’s all infinitely better,” Elspeth said. “But I wonder whether there isn’t the same tendency to bicker, and whether the moral energy that gave us the religious extremism isn’t still there, just the same, but showing itself differently. There are still plenty of people who are keen to tell other people what to do.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAngus agreed. “There certainly are. We may not be lectured from the pulpit any longer, but we’re certainly lectured. And we might be every bit as intolerant of dissent as we were back in those days.”

The silence that had attended the earlier recollection of social solecism now returned, but only for a few moments. Then Matthew said, “Our history is so violent.”

Advertisement

Hide Ad“Isn’t everybody’s?” asked Domenica. “We’re a violent species.”

Elspeth looked pained. “There must have been some peaceful societies. Domenica, you’re an anthropologist – you must know of some society where …” She shrugged. “Where people share and co-operate and look after one another.” Sometimes, she thought, such desiderata seemed so unlikely as to be impossible.

“Eden?” suggested Angus.

“The Peaceable Kingdom theme,” mused Matthew. “Do you know those pictures? There’s that famous one in the Phillips Collection in Washington. I’ve actually seen it. All the animals are together – the lion and the lamb, and so on. All are at peace with one another.”

“That’s wishful thinking,” said Domenica. “Not painted from life.”

“Perhaps,” said Matthew. “But then don’t we have to have some idea like that – somewhere in the back of our minds. An idea of civilization? And idea of what things might be?”

“Nobody uses the word civilization these days,” said Domenica. *

Advertisement

Hide AdMatthew reached for his glass of wine. “That’s the problem,” he said. “We don’t believe in anything … except things – the material.”

Angus looked at him. He was right. We had forgotten about the spiritual; we had forgotten about the idea of civilization; we had forgotten about how important it was to be courteous to one another and to love your neighbour. And nobody talked about these things except in a tone of embarrassment or apology, but at least they could do so here, in this dining room, in the warm embrace of friendship, under the gaze of these gentle hills, this lovely country, this blessed place.

Advertisement

Hide Ad* Not entirely true: see, for example, In Search of Civilization by the Scottish philosopher, John Armstrong, a profound defence of the tarnished concept.

© Alexander McCall Smith, 2021. A Promise of Ankles (Scotland Street 14) is available now. Love in the Time of Bertie (Scotland Street 15) will be published by Polygon in hardback in November 2021