Robert Louis Stevenson's guide to Edinburgh's 'glories and absurdities'

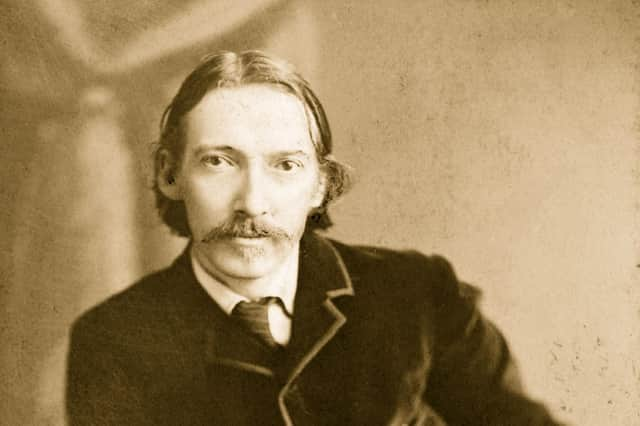

Robert Louis Stevenson was never intended by his family to be a writer. The Stevensons were a clan of lighthouse engineers, and were responsible for the building of most of Scotland’s important lighthouses, often in spectacularly remote, and indeed romantic, settings. In Scotland today, anybody who is familiar with the country’s coastline, is likely to use the term Stevenson lighthouse about any of these magnificent, lonely structures. That was what the Stevensons did – and they did it for generations.

RLS (as Robert came to be known) had different ideas, though, and although he went along with the family plan so far as to study engineering at the University of Edinburgh – not in a very serious way – it was clear that the engineer’s drafting table was not going to satisfy this imaginative and romantically-minded young man. He switched from engineering to law – an eminently suitable profession in the eyes of the particular sector of Edinburgh society into which he had been born. At least he qualifed in this, and was duly called to the bar, but once again the settled, predictable life of the Edinburgh professional was not to be for him.

Advertisement

Hide AdHe travelled in France and he began to write, discovering that he was a born storyteller. Over the years that followed, he produced an extraordinarily wide range of books – not only the novels for which he is today principally remembered, but travel books too. Edinburgh: Picturesque Notes falls into his catalogue of non-fiction, much of which is no longer remembered. Yet a number of these books have had their following over the years and have survived to the present day. Stevenson’s collection of poetry for children, A Child’s Garden of Verses, has been through numerous editions and remains in print today.

Stevenson is principally remembered for a small number of novels that entered the canon of classic adventure stories. Kidnapped and Treasure Island are perhaps the best-known of these, but we might remind ourselves that Stevenson was also the author The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, the title of which has entered the English language. Leading a Jekyll and Hyde existence is testament to the impact of that novel on many thousands of readers over the years.

Stevenson enjoyed a considerable reputation as a writer during his lifetime. The nineteenth-century appetite for Scottish fiction, having been stimulated by the towering figure of Sir Walter Scott, was ready for further contributions of a romantic and historical nature, and Stevenson was happy to oblige. Yet in spite of his widespread popularity – or, perhaps, because of it – literary critics have been slow to accept Stevenson as a serious writer, regarding him, in some cases, as beneath their notice. Stevenson was considered by some to be almost childish in the delight he took in a stirring story, and his apparent lack of interest in psychological complexity did not help him in establishing a reputation amongst the literati. And yet there have always been those who have appreciated Stevenson as a lively and amiable literary companion – an antidote, perhaps, to the dreary, depressing and pessimistic themes that many writers of greater reputation indulged in. Stevenson is a sunny writer. He is lively; he is fun; he has no interest in wallowing in misery or despair.

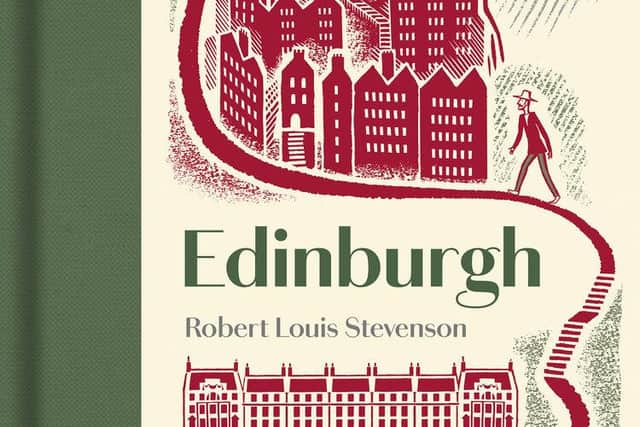

All of these qualities are evident in Edinburgh: Picturesque Notes, one of Stevenson’s earliest books, that was based on a series of articles he had begun to publish about the city of his birth. This book was intended to afford the reader an insight into the city that lay at the very heart of Stevenson’s view of the world. This was the city which that sickly, imaginative youth looked out upon from his bedroom window in Heriot Row, in Edinburgh’s Georgian New Town. This is the city whose atmosphere Stevenson imbibed from his earliest years and whose image, in all its spiky, misty, stirring complexity remained engraved on his writer’s heart. If every writer has his place that comes to mind when he or she closes his or her eyes, then for Stevenson it is the narrow closes of Edinburgh’s Old Town, the dank tenements, the windy passages that do that work. Stevenson inhabited Edinburgh in the fullest possible sense. He knew its twists and turns, its colourful, violent history, its glories and absurdities, its pretences and ambitions. And that is what he wanted to write about in this book. This is not a formal history nor a dry gazetteer. This is one particular young man’s engagement with a complex city that, like many a human lover, remains reticent, almost shy, in the face of the address of its admirers.

Stevenson’s prose seems remarkably modern. While Walter Scott strikes many modern readers as excessively wordy and even sometimes convoluted, Stevenson’s writing strikes the twenty-first century ear as still being fresh and intensely readable. There is a conversational tone to it, and this is particularly the case in this book, where we feel that we are in the company of an agreeable and relaxed guide giving us an anecdotal run-down on Edinburgh over a cup of coffee or a lunch. This is not a compendium of dry facts – this is an account of why Stevenson found Edinburgh so fascinating and such a rich source of inspiration for his writing. This is a walk through parts of the city that have survived to this day in very much the same form as they were during his lifetime. If we were to stroll down Heriot Row with him today, there would be no surprises for him when we reached No. 17, although he might not have expected a plaque.

A striking feature of Edinburgh: Picturesque Notes is the fact that Stevenson did not write an encomium to the city. He is sensitive to its achievements and is ready to acknowledge the city’s fragile beauty, but in his amusing and spirited introduction he makes it clear that there are features of Edinburgh that he finds risible, and even absurd. Those of us who know the city well will understand exactly what he is talking about. Edinburgh sometimes takes itself too seriously. It loves a bit of show; it loves a bit of ceremony; it is quick to remind us that it is the city of the Scottish Enlightenment and an ancient capital too. And yet it is not a very big city and its grandeur has to rub shoulders – or certainly had to do so in Stevenson’s time – with humbler features, with reeking tenements, grubby urchins, and all manner of street life.

Advertisement

Hide AdAt the beginning of this book there is a wonderfully vivid description of a procession undertaken by the Lord Lyon and his officers – the heralds and pursuivants – in their colourful tabards, while all about them stand what a later Edinburgh writer, Robert Garioch, would describe as “the keelies o’ the toon” – the riff-raff, so to speak. This leads us to a core aspect of Stevenson’s feeling for his city – his understanding of its duality. This, after all, is the city that spawned Jekyll and Hyde, and that was the home of the infamous Deacon Brodie, the civic worthy by day and the house-breaker by night. This theme of the juxtaposition of good and bad, seemly and unseemly, continues throughout the book.

There are many places, too, where Stevenson is frankly irreverent, pricking pomposity and pretence in a way that many later writers have sought to do, but have not necessarily succeeded at doing with the same good humour and wit as does Stevenson. At times, perhaps, he allows his feelings to run away with him. The section on the erection and spread of villas in what became Morningside is a real broadside against the suburban spread that occurred on Edinburgh’s South Side in the latter half of the nineteenth century. Enemies of twentieth-century architectural brutalism will not forebear to cheer when they read Stevenson’s withering comments on the speculative domestic building of his time, and contemporary conservationists will find much to commend in the importance that he attaches to the human scale in our planning of our cities.

Advertisement

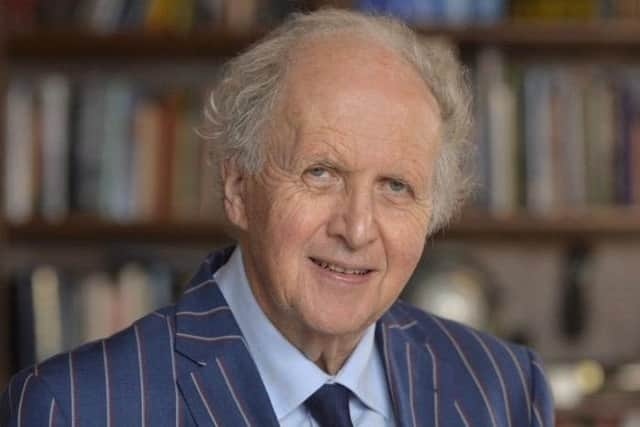

Hide AdEvery city is, for its inhabitants, a living map. As I walk through Edinburgh, I find at every turn there is something to remind me of the history of the place and of my own experience of it over the years. Here I met a friend; here I was happy one day; here I remembered some event that had taken place a long time ago; here I saw something I would not readily forget. We read a city as we walk through it. We read its past; we converse with its dramatic personae; we become familiar with its stones, its angles, the glimpses it affords us of streets that lead off somewhere we might one day explore. That is the tenor of Stevenson’s book. It is a ramble. It is at times a prose poem. It is a stream of consciousness memoir about living in a town so gorgeously romantic it could be an opera set; it is a litany of whispers and echoes; it is a love song to a city. It is all of these.

Edinburgh, by Robert Louis Stevenson, illustrated by Iain McIntosh and with an introduction by Alexander McCall Smith, is published by Manderley Press, price £16.99, see https://www.manderleypress.com/

A message from the Editor

Thank you for reading this article. We're more reliant on your support than ever as the shift in consumer habits brought about by coronavirus impacts our advertisers.

If you haven't already, please consider supporting our trusted, fact-checked journalism by taking out a digital subscription at https://www.scotsman.com/subscriptions