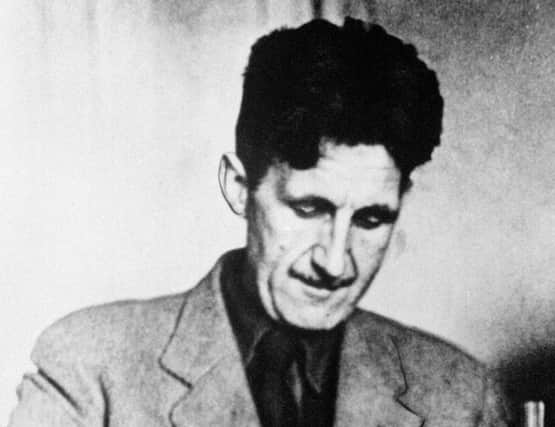

Orwell out of copyright: a cornucopia of new editions

Eric Blair, who was also George Orwell, died in 1950 at the age of 46. This means that, as of 1 January, the vast majority of his work is newly out of copyright, and publishers are free to reprint what was published before his death without having to pay royalties to his estate. It’s not quite a free-for-all because as DJ Taylor, perhaps the best of his biographers, pointed out in a recent article in The Critic, there have been editions of some books with new material published since 1950 which are still protected by copyright. These include editions of his letters.

Nevertheless, there’s a cornucopia of new editions. Birlinn, in their Polygon list, have brought out what they call the Jura edition of Nineteen Eighty-Four, with what I may be permitted to call an admirable Introduction by my son Alex, in which he describes Orwell’s life there and corrects a good many misconceptions of the island offered by English writers.

Advertisement

Hide AdPolygon have also published The Last Man in Europe, a biographical novel by Dennis Glover. This is interesting, sympathetic and intelligent, though it plays down some of Eric Blair’s more problematic sides, notably his often inept pursuit of girls in his youth and women in his maturity. On the other hand, Glover writes convincingly of the contribution to his work – especially Animal Farm – made by Orwell’s first wife, Eileen. There are a few unimportant inaccuracies, very minor ones, but in general Glover’s eagerness to relate Orwell’s own experience to the making of his dystopian satire Nineteen Eighty-Four is persuasive.

Glover has a higher opinion of Orwell’s four pre-war novels than I do, indeed considerably higher than Orwell did himself. He even thinks well of A Clergyman’s Daughter. I tried to read it again recently and soon gave up. Orwell regarded all four books as failures (which says much for his integrity and judgement), though there’s something to be said for the last of them, Coming Up for Air.

His non-fiction books, The Road to Wigan Pier and Homage to Catalonia, retain historical interest, and it was his experience of the Soviet role in the Spanish War which opened his eyes to Russian Communism’s brutality and perversion of truth; the experience which informs both Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four, even if much of the second novel was drawn from his experience of wartime London and the Ministry of Information.

Both books are masterpieces, the first much influenced by Swift – Gulliver’s Travels was one of his favourite books. Yet Orwell wasn’t really a natural novelist; he had too little interest in other people as individuals, and much of his best writing is to be found in his essays and journalism.

Some of this is inevitably dated, especially the long wartime essays written for American magazines. These are of only historical interest now, and most of what he predicted was wrong. Far more however remains remarkably fresh and enjoyable, so it’s no surprise that new editions are now tumbling out.

Pushkin Press have issued two little books of essays: one, Inside the Whale: On Writers and Writing, the other England Your England: Notes on a Nation. Both have the elegance one expects from Pushkin and both, blessedly, are of a size you can slip into your pocket. The first has an excellent essay on Dickens, while I remember the title essay enthralling me when I read it in my first year at university; it still seems pretty good, though I now disagree with many of the judgements. The other opens with that wonderful essay, “Decline of the English Murder.”

Advertisement

Hide AdMeanwhile Renard Press is bringing out four of Orwell’s best essays in individual volumes. These include “Politics and the English Language,” something I must have read at least a dozen times. Some of what he says there about political language is dated, or at least the examples offered are, but anybody who wants to write better will learn much from this essay. Moreover, the examples he offers of bad writing are still relevant today. Indeed, I would say they are even more to the point now than they were 70 and more years ago. I commend especially Orwell’s translation of a famous verse from the Book of Ecclesiastes into 20th century bureaucratic/academic language. It is simultaneously hilarious and a dreadful warning.

A message from the Editor

Thank you for reading this article. We're more reliant on your support than ever as the shift in consumer habits brought about by coronavirus impacts our advertisers.

If you haven't already, please consider supporting our trusted, fact-checked journalism by taking out a digital subscription at https://www.scotsman.com/subscriptions

Joy Yates, Editorial Director