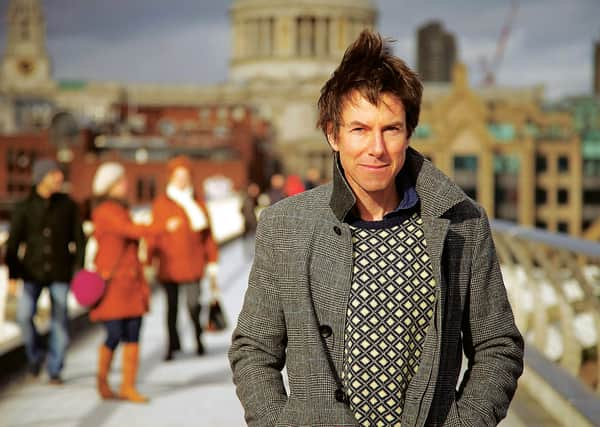

Michael Bond interview: “Until I wrote this book I didn’t realise quite how terrifying getting lost is”

To the hills of Invergeldie and all those who have walked in them.” That’s the dedication at the start of Michael Bond’s new book Wayfinding, and those hills just to the north of Comrie are where he first got to grips with its subject – the science behind finding and losing our way.

It’s one of the most fascinating books I have read for a long while, not least because of how it opens up so many other subjects. The illustrations alone make that point. On one page, there’s a map showing how much further grandparents and parents walked across a city than their children do today. Turn the pages and there’s Tolkien’s map of Middle Earth, a topographically accurate map of the London Underground, an atlas of Inuit trails across arctic Canada, or diagrams showing how a rat’s brain works out where it is. Meanwhile, the text makes readers think up questions of their own: when I visit a city for the first time, how do I find my way around? When I visit it for the fifth time, how reliable is the “cognitive map” I have already made of it? Can cities be designed so people don’t get lost? Can spatial tests predict Alzheimer’s or wayfinding skills stave off mental decline? Those hills of Invergeldie turn out to hold the answers to more questions than one might have first thought.

Advertisement

Hide AdBond, an award-winning science writer and former senior editor at New Scientist, is too fastidious to put it quite like that. The countryside and winding lanes around the Hampshire dairy farm on which he grew up also helped develop his navigational skills, he says, and in any case he’s not claiming to be an expert navigator. But the hills around his grandparents’ Scottish sheep farm, where he spent many of his holidays, were also where he felt even more free to wander and, from the age of eight, did so with a compass. It was there too, that he learnt about noticing the landscape as closely as our ancestors must have done: that you could still see buzzards, ravens and merlins at Craig nan Eun (rock of the birds) or, at the top of Tom a Mhoraire (hill of the cloudberries), still find the fruit after which it was named.

Noticing is fundamental to navigation. The Polynesians who settled the Pacific islands between 300 and 1000AD, he points out, sailed for hundreds of miles without any way of establishing longitude or latitude yet worked out where they were by noticing “the patterns of waves, the direction of the wind, the shapes and colours of clouds, the pull of deep ocean currents, the behaviour of birds, the smell of vegetation and the movements of the sun, moon and stars.” On the other side of the world, the Inuit were, at least in the days before GPS, equally impressive. In the 1930s, British explorer Freddie Spencer was fogbound while kayaking off the coast of Greenland with an Inuit hunting party. While he panicked, they didn’t. Instead, they paddled down the shorelines listening to the slightly differing territorial song of male snow buntings. When they identified their local birdsong, they turned inshore.

In the hills of Perthshire, Bond’s own navigational skills were nowhere near as fine-tuned, but he did at least master the basics.

“The landscape around the farm was really good for developing my navigational skills,” he says. “For example, early on we all imagine that the landscape is ranged on simple north-south lines, and yet here the hills went from northwest to southeast. And although they have quite a lot of craggy rocks, the moorland above can be quite flat and when visibility is poor, you really need that compass.”

Navigation, he points out, is fundamental to homo sapiens. We wandered further than the neanderthals, so a sense of direction mattered more – so much so that explaining it might have been where our language and indeed our capacity for abstract thought began. And just as knowing where we are is central to our mental health, so being lost is one of our most primal fears.

“Because I’ve never been totally lost,” he says, “until I wrote the book I didn’t realise quite how terrifying it is. When you’re really lost in a wild place it is absolutely traumatic. You really do feel as though you could die. That kind of reaction seems to be hardwired within us – because for our early ancestors being lost would indeed have meant almost certain death.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAs part of his research, he talked to search and rescue teams in both Britain and America. When lost, apparently, people seem unable to stay where they are and await rescue (the best tactic), yet ironically, one of the more famous recent “missing walkers” stories in America did just that, and died in her tent in thick woodland just two miles from the Appalachian Trail in Maine. Hoping to understand the psychology of lostness, Bond visited the spot. “Stupidly, I wandered out into the woods without my compass. I was only about 80 yards away [from the trail], but I got lost immediately. It was only for a few minutes, and not remotely comparable, but I was genuinely frightened.”

To reach that spot in the Maine woods, Bond relied on GPS. Normally, he doesn’t, and – unusually for a freelance journalist – doesn’t even have a mobile phone.

Advertisement

Hide AdThe reasons are spelt out in his book. In our speeded-up culture, we notice less about the world around us than our ancestors did: today’s Inuit, with their Skidoos and GPS, no longer need to listen out for male snow buntings and are forgetting how to do so, just as British children who are driven to school cannot describe what they pass by en route half as well as those who walk there. High-tech shutters, he argues, are coming down on free-range childhoods, while at the other end of the age spectrum, the navigational skills that might help (more research is needed) to keep the lostness of Alzheimer’s at bay are beginning to atrophy.

For his next book, he says, he’ll be writing about the psychology of fandom, whether of the Beatles or, say, Jeremy Corbyn. In the meanwhile, if you want to understand what rats can teach us about better-planned cities, why walking into a different room can help you find your car keys, or how your brain’s grid, border and speed cells combine to give us a sense of direction, this book has all the answers.

Wayfinding by Michael Bond is published by Picador, price £20

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.