How Treasure Island was born out of Robert Louis Stevenson trying to amuse his stepson on a wet summer holiday in Braemar

It’s raining. It’s been raining for what seems forever, splattering against the window. Outside clouds hang low, shrouding the hills. Inside, the room is warm, a fire crackles and spits. A teenage boy sprawls across an armchair, a look of absolute indifference to everyone and everything stitched on his face, a look only a teenager can perfect.

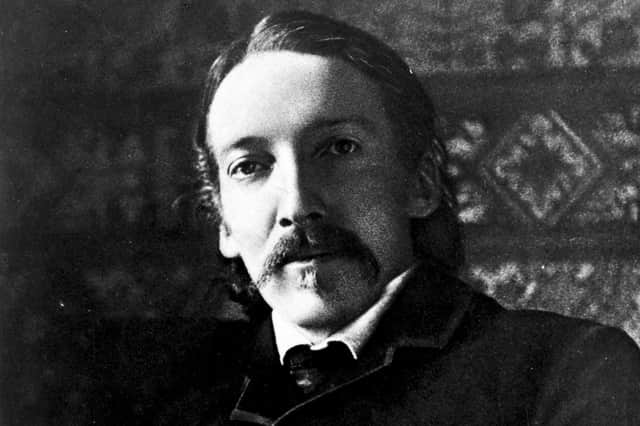

At a table, a slim man is bent over a piece of paper, long hair hiding his face, long fingers holding a pencil with which he draws quickly, sketching dark lines on the page. He sits up and regards his work, tucking hair behind an ear, adds two words and hands it to the boy.The boy can’t prevent a flicker of interest lighting his eyes. “Treasure Island?” he says. Robert Louis Stevenson smiles.

Advertisement

Hide AdAnyone who has ever taken a holiday in the Highlands, child or adult, has been in that room. A holiday challenged by our weather; give me something, anything to break the boredom.

My children have become so practised at Scottish holidays they have their own language for it. A ‘Mull picnic’? Lunch in the boot of the car, rain drumming on the roof, somewhere out there a view.

Yet we owe that summer weather. I certainly do and so, over the last 140 years, do the millions who have taken pleasure from Treasure Island, The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, Kidnapped and more, stories that have been loved like few others from this country. Perhaps no others.

It was in August 1881 that Robert Louis Stevenson arrived in Braemar for his summer holiday. He was 30, a writer without a novel to his name, a wanderer unsure where home was, recently married with a wife and stepchildren to support. He had the mind of an adventurer housed in a body he feared would not allow him long life. Ill-health had pursued him from childhood. He was at a crossroads.

The Stevenson party, his American wife Fanny, her teenage son, Sam, Louis’s parents and former nanny, took Old Mrs McGregor’s cottage. And the rain began to fall. Stevenson sat by the fire with his father, Thomas, the lighthouse engineer, a domineering figure.

What should I do, Dad?

Stevenson floated book ideas. A biography of the Duke of Wellington maybe? And considered a change of tack. Should he even abandon the dream of writing novels, his dream of becoming Scotland’s Shakespeare? Become instead a historian? There was a position at Edinburgh University – Stevenson began to write letters, drumming up support.

Advertisement

Hide AdHe had another, more immediate role to deal with. A fatherhood of his own. Sam was 13. He’d suffered the death of his young brother, a peripatetic home life, an absent father. He soon grew close to his stepfather, an attachment that lasted until Stevenson’s death. It was not surprising. Stevenson was magnetic, his company sought by men, women and children. Stepfather and stepson played sprawling wargames with Sam’s tin soldiers – and printed reports of the battles on a small press.

In Braemar, as rain fell, Sam grew bored of soldiers, of painting, of everything, and so Stevenson put thoughts of history on hold and reached for his pencil. He drew Sam a map, one rich in detail, Spyglass Hill, Skeleton Island, the Stockade – Treasure Island. It grabbed Sam’s attention and sparked an idea in Stevenson’s mind.The story came together swiftly… the Admiral Benbow Inn, Blind Pew, the Black Spot. Stevenson wrote in the morning, in bed on a specially made desk, then read the chapters to his family. They adored it, threw in ideas of their own; the scene where Jim Hawkins hides in the apple barrel and overhears mutinous plans suggested by his father.

Advertisement

Hide AdStevenson, at first, loved the story, loved the process of writing a chapter then reading it to his entranced family. He wrote to a friend.“If this don’t fetch the kids, why, they have gone rotten. It’s all about a map and a treasure, a mutiny and a derelict ship, a Sea Cook with one leg and a sea song with the chorus ‘Yo-ho-ho and a bottle of rum’.”

A visiting journalist suggested publication. Stevenson uummed and aahhed as Stevenson often did, until money was mentioned. A deal was reached with Young Folks, a children’s magazine, to publish chapter by chapter and under a pen name, Captain George North, because Stevenson fretted it would sink without trace.

He need not have worried. Treasure Island captivated its audience from the start. It still does. Read it and be struck by the pace, the characters, especially Long John himself, the arch-villain with a silver lining. And be struck by its violence and harshness, the adult world young Jim hurtles into is one with few redeeming moments. The scenes in which Silver knifes a man in the back or Jim shoots dead Israel Hands are brutal.

“He rose again to the surface in a lather of foam and blood and then sank again for good.”

Treasure Island is dedicated to Sam Osbourne. It’s a classic. There can be a snootiness about Stevenson, there always has been. He suffers for his familiarity, everyone knows about pirates with one leg or Jekyll-and-Hyde characters. They have become clichés, which should only underline their initial and lasting brilliance.Treasure Island was not done, though. Stevenson’s health and another familiar problem got in the way. He always had trouble finishing his works. He was a man of extremes. He’d work hard, write himself into sickness, followed by weeks going round in circles.After 15 chapters he was stuck. He and Fanny had left Braemar for Switzerland. His chest needed a break from Scotland.

But Young Folks needed its chapters. If Stevenson was to be paid he had to finish. Treasure Island is narrated by Jim Hawkins – apart from three middle chapters where Jim is replaced as our storyteller by the doctor. This is how Stevenson overcame his writer’s block. I doubt an editor today would allow such an escape route. But it works.Stevenson had no choice over the escape route Fanny offered from Scotland. His chest condition meant, so doctors and wife convinced him, if he remained in his home country he would die.

“I’m for Scotland but Scotland’s not for me.”

Advertisement

Hide AdHe was to have one more significant summer trip home, when his father died and Stevenson returned to bury him. It was cold, wet and it nearly buried Stevenson. On the last day of May 1887, he left Edinburgh and Scotland and never returned.

Stevenson died in Samoa seven years later, a long way from home. But not in his thoughts. His last work, the unfinished Weir of Hermiston, was set in his homeland.

Advertisement

Hide AdHis love – and fear – for Scotland is there in the work he produced outside its borders. He worried the Scots language, in which he often wrote, was dying. Banished abroad, he produced Kidnapped and Catriona, Scottish novels to their core. He wrote of his “ambition of the heart” to have “my hour as a native Makar.”

In so many ways, he has had that. And not hours but years, more than a hundred of them.

Stevenson was a man of contradictions and contrasts, his own Jekyll… you can fill that bit in. If he lived in the Scotland he loved, his country would kill him.

But, perhaps, if his country had not soaked him and Sam that dreich summer of 1881, he would never have become the giant of Scottish literature that he most certainly is – and always will be.

Finding Treasure Island by Robin Scott-Elliot is published by Cranachan on 3 November, priced £7.99

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.