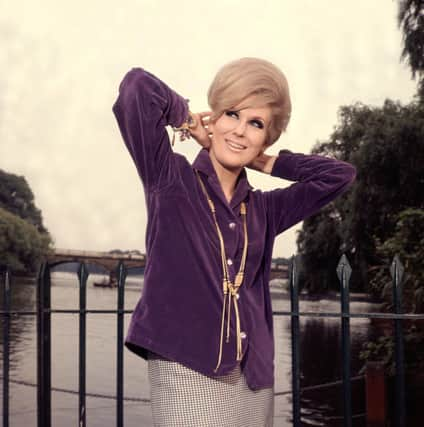

How Dusty Springfield and Karen Carpenter paved the way for change for women in music

In my work as a music writer I focus on women artists, because for too long they didn’t get the recognition they deserved. Two pioneers in particular – Dusty Springfield and Karen Carpenter – fascinate me, because of the way they navigated deeply troubling issues with mental health, yet still created astounding pop music.

This week Dusty, my biography of Dusty Springfield is published as a special reissue to mark the 25th anniversary of the singer’s death, on 2 March 1999. Since her passing, Dusty’s stature and legacy as a pop icon has grown. Songs like Son Of A Preacher Man and The Look Of Love still get widespread radio play, she is one of the top-streamed 60s artists on Spotify with over 8.6 million listeners, and next year sees the release of Dusty, a biopic by My Left Foot director Jim Sheridan.

Advertisement

Hide AdBut when I first published Dusty in 1989, she was just emerging from a decade in obscurity, baited by the tabloid press about her sexuality, and considered a troublemaker by many in the industry. “She’d got quite a reputation for being a hard case. Other female singers like Vera Lynn or Anne Shelton never spoke up. They just went into the studio, recorded and walked out. Dusty took a more personal interest,” her producer Ivor Raymonde told me. “Bad musicians annoyed her and the tempo had to be just so. She was a perfectionist, like me, so we got on well.”

Dusty was very active in the studio, contributing ideas to song arrangements and experimenting with sound. She even trailed microphones down to the ladies’ toilets at Phillips’ Marble Arch studios, where she felt the ambience was better. “I was struggling to establish something in England that hadn’t been done before,” she told me in 1988, “To use those musical influences I could hear in my head.”

Today Dusty would be given credit as a producer, but because of the sexism of the time, her contribution was unacknowledged. Fusing a love of US soul music with overblown romantic pop, Dusty created a new sound that, along with The Beatles, led to her becoming a key star in the 60s British Invasion. She was also an activist, refusing to play to segregated audiences in apartheid South Africa, and a champion of the Gay Liberation movement at a time when being out and gay was taboo.

Although she spoke out in support of gay rights, Dusty kept her lesbian identity secret throughout her life. “Without a doubt, her lesbianism was the icing on the cake of her ‘difficult reputation’”, her songwriter friend Allee Willis told me.

Feeling the pressure to invent boyfriends and pretend she was straight took its toll on her mental health, exacerbating issues she had with anxiety and addiction. Her former lover, the singer Julie Felix, remembered that they had to be constantly on guard. “We were terrified of being found out. My mother would say the word ‘lesbian’ as if it was worse than being a serial killer. We had to lie, it was such a harsh pressure, like being in a vice.”

In a bid to escape tabloid scrutiny in the UK, Dusty moved to Los Angeles in 1970. But the American music industry didn’t know what to do with a Home Counties white girl singing soul music, so Dusty’s career spiralled and she spent years struggling with depression. It wasn’t until 1987’s aptly titled What Have I Done To Deserve This?, her soaring hit with the Pet Shop Boys, that Dusty made a glorious comeback. Even though she died young of cancer at 59, she found peace of mind in the last few years of her life because she was appreciated, people had begun to realise she was a national treasure.

Advertisement

Hide AdKaren Carpenter also suffered from having to project an inauthentic image. With their rapturous harmonies and lush production, the Carpenters were one of the biggest acts of the 1970s, selling over 100 million records with global hits like Close To You, Only Yesterday and Please Mr Postman. Marketed to conservative middle America as easy-listening pop meant that Karen was just seen as the decorative frontwoman, while her brother Richard was considered the real genius behind the music. This sense of a woman without agency was compounded by her tragic early death in 1983 from anorexia, aged just 32.

For a woman to be at the top of her game in the 1970s music industry, I knew there had to be more to Karen’s story. In researching my book Lead Sister I interviewed former lovers, musicians and friends to discover a powerful, driven artist. Karen was an accomplished drummer as well as a singer, a tough cookie who was comfortable touring for months with the guys in the band, and an innovator in the studio alongside her brother.

Advertisement

Hide Ad“She was the boss, the one in control of stagecraft and directing the musicians. She was an amazing singer and drummer – real precision work,” recalls DJ/producer Jeff Dexter, who met Karen backstage in 1974 when the Carpenters were rehearsing their Talk Of The Town show.

Karen was constantly questing as an artist. When Richard went into rehab in 1979 to beat quaalude addiction, she travelled to New York to record a solo album with producer Phil Ramone.

“Karen yearned for more control over her art. That was a big part of her motivation,” says Bob James, a renowned jazz/fusion arranger on the project. She made a great female soul/pop album, but A&M Records shelved it because it didn’t fit with the Carpenters’ oeuvre, and they didn’t want to take a risk.

After that her mental health deteriorated and her anorexia became chronic. But even in the throes of her eating disorder, Karen continued to make music with remarkable willpower and focus.

“She had this way of talking – ‘I’m gonna lick this thing, I know I can do it’,” recalls her friend, the singer Cherry Boone O’Neill. “Karen had this public persona of being feminine and frail-looking but she could talk like a truck driver. That was a surprise! But she was very determined and hopeful.”

In the 1970s there was very little knowledge about how to treat anorexia, and Karen’s therapy came too late. “She was in such a difficult position being the hub of the big wheel that was the Carpenters,” says O’Neill. “She had so many people depending on her to be functional and present. Really she should have taken a long time off to recover.”

Both Dusty and Karen paved the way for change.

Advertisement

Hide AdCurrent female artists like RAYE, Lizzo, Lady Gaga, Adele and Billie Eilish have spoken out about the pressure they feel in a business that exploits women, a view supported by the recent UK Women and Equalities report into misogyny in the music industry. Although the problems persist, there is more awareness about how that pressure has huge detrimental effects on mental health, and female artists are becoming better protected.

Back in the 1960s and 70s Dusty and Karen Carpenter had to battle their demons in private, so they channelled those feelings into their music, making moving, unforgettable pop moments. That’s why they are remembered, and why their stories continue to fascinate us today.

Dusty: The Classic Biography (Michael O’Mara, £10.99) and Lead Sister: The Story of Karen Carpenter (NineEight, £10.99) both by Lucy O’Brien are out in paperback now.