Book reviews: The First Ghosts, by Irving Finkel | The Heart of Things, by Richard Holloway

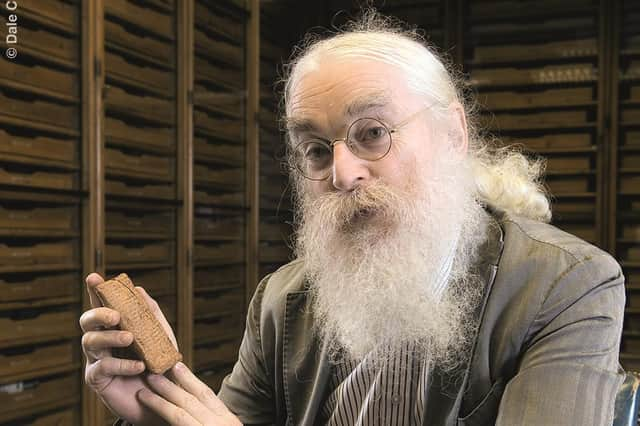

Even if you don’t believe in ghosts, you probably believe that there are people who believe in ghosts. This is the fundamental premise of Irving Finkel’s marvellous new book. Finkel is an expert in Mesopotamian cultures at the British Museum, and is one of the most clever, and nicest, of people it has ever been my pleasure to encounter. He begins this work with his own regret that he has never seen a ghost, despite a school friend having seen a woman, in black clothes, in his bedroom at night, muttering “go away”. But this is no impediment to his fascination with the idea. As someone who can read cuneiform, the earliest form of writing, he is an ideal guide to what our early ancestors thought about ghosts. In a nutshell: they believed in them.

Over the course of the book, he ranges over the Sumerian and Akkadian sources about ghosts, and it is a fascinating journey indeed. As a good sceptic, he is sceptical about his own scepticism. Towards the end of the book he gives a list of reasons why someone might claim to have seen a ghost: “Lying, inventing, mistaken, delusional, hysterical, hallucinating, drunk, drugged, delirious, hypnotised, influenced by external images, repeating something heard, regurgitating something read, undergoing freak weather conditions, experiencing a trick of the light, experiencing a trick of the dark, affected by stress, undergoing financial worries, undergoing marital problems, overworking or eating unwisely”. He very precisely says that though all might be possible, since they are anecdotal, for all of them to be impossible means either everyone is wrong at some level or everyone is colluding in a conspiracy. This is humane as well as wise. As a friend of my father’s used to counsel, there are things that are true and things that are true to the person telling you.

Advertisement

Hide AdMost of the book is about the very earliest accounts of ghosts. This means a detailed study of funerary rituals, belief in the afterlife and the concept of the soul. The sense of “The Land Of No-Return” as a place of dust, ashes and darkness, with a hierarchy of overlords and ladies, is described in details that utilise both archaeology and written texts, such as the Descent of Innana, the deaths of both Enkidu and Gilgamesh, and a very strange work that I did not know called An Assyrian Prince in the Netherworld.

Finkel has a theory about the purpose and meaning of this work, but it would be wrong to reveal the detective story at the book’s centre. Although I was obviously going to be more interested in the literary texts, I found myself entranced by the more bureaucratic ones. The peoples around the Euphrates were great record-keepers, so we have a staggering list of 28 unhappy or resentful ghosts, followed by 34 for unnatural deaths. That is before we get to necromancy and exorcism, with the proper uses of dollies, chairs, bread, “pure water”, skulls and donkey urine to do the business.

The point however, regardless of the particular cultural manifestations, is the belief, and Finkel does not condescend. In describing the difference between a family ghost and a vengeful spirit he has a lovely metaphor: a family ghost is like seeing a mouse in the kitchen at night. You are startled, you realise it means no harm and if it keeps coming back you might consider getting in pest control.

The book does not cover Chinese ancestor worship, and how to placate those spirits, but a specialist is allowed his specialism. The chapter on the Bible is a tad sketchy – there is only one “summoned spirit”, Samuel, and Saul asking for him to be conjured is wrong not because the necromancy is wrong, but because Saul has explicitly forbidden the practice. It is about hypocrisy, not table-rapping.

There are two people who don’t die in the Bible: Enoch and Elijah. (Jesus did die, and the Harrowing of Hell, the great prison-break on Easter Saturday, is in the apocryphal Gospel of Nicodemus). Richard Holloway in his anthology of poems and prose about facing the inevitable, The Heart of Things, is as open-hearted and wide-minded as Finkel. If Finkel wonders about the after, Holloway concentrates of the before. The word “sermon” is now often pejorative, implying hectoring and brow-beating. Holloway is the opposite, in that he teases out the meanings of works by Virginia Woolf, Edna St Vincent Millay, Laurence Binyon, AE Housman, Amy Clampitt and Philip Larkin.

He is genial if melancholy company, and his self-critique about whether all writers are spurred by vanity makes for rather rueful contemplation. But if I learned something on every page of Finkel, I paused on every page of Holloway. It is good to know that Babylonian spells were probably mumbo-jumbo versions of Elamite; it is good to linger over a line of Mahon or MacNeice. HoIlloway’s commentary and anthology will indubitably bring a crumb of comfort to many readers. It ends with one of his own poems (I presume) with the lines “… endings / there were always endings, / but I was always glad I went”. It ends “it was, it WAS! / AMEN.” This is Hallowe’en. It is the anniversary of my brother’s death tomorrow. I am glad, so glad, for both books.

Advertisement

Hide AdThe First Ghosts, by Irving Finkel, Hodder & Stoughton, £25

The Heart Of Things, by Richard Holloway, Canongate, £16.99

A message from the Editor:

Thank you for reading this article. We're more reliant on your support than ever as the shift in consumer habits brought about by coronavirus impacts our advertisers.

If you haven't already, please consider supporting our trusted, fact-checked journalism by taking out a digital subscription at https://www.scotsman.com/subscriptions