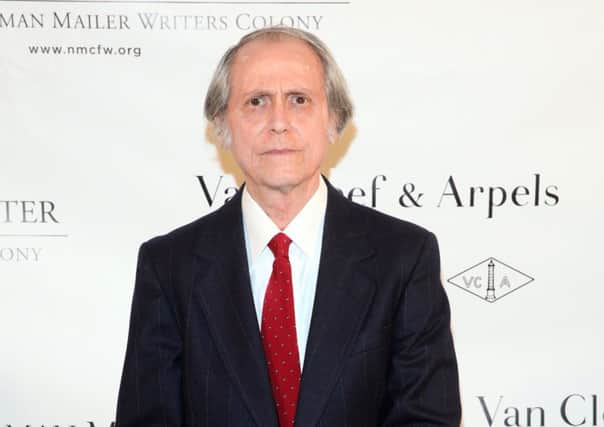

Book review: Zero K by Don DeLillo

Zero K by Don DeLillo | Picador, £16.99

In terms of contemporary American literature’s Alpha Males, I was always more interested in Coover, Gaddis, Pynchon and DeLillo than Roth, Updike, Mailer and Bellow.

DeLillo’s thematic quartet of novels from 1982 to 1991 – The Names, White Noise, Libra and Mao II – spoke of a world of conspiracy and celebrity, spectacular terror and deadening images. Underworld, in 1997, was an epic in every sense, about what is literally and metaphorically buried – the central character is a “waste management consultant” with a secret. It was no coincidence that Pluto, the Roman god of the underworld, had authority over death and wealth. In the wake of that masterpiece, his output has been interesting, but perhaps, thinner. The Body Artist was a flinty fable about art and grief; Cosmopolis a bit of a re-tread around capitalism’s excesses and losses. Falling Man, his “9/11 Novel”, was tight-lipped and seemed to describe, with an air of resignation, a world he had already imagined. By far the best was Point Omega, which exemplified his assertion that writers must “oppose systems”, describing the relationship between a film-maker and a reclusive academic who had been tasked by the government with imagining war as a haiku.

Advertisement

Hide AdNow we have Zero K, its title eerily echoing Point Omega: these are novels about terminal situations. It is one of the only books I have read this year that I know I will re-read and re-read. It stands in relationship to his earlier work as Beethoven’s late string quartets do to the Choral Symphony.

It is narrated by Jeffrey Lockhart, a man whose peculiar form of rebellion against his father is to take jobs with titles like “systems administrator” or “human resource planner”, anything where he is “outside the subject, almost always, whatever the subject was”. His father, Ross, is a man of “companies, agencies, funds, trusts, foundations, syndicates, communes and clans”, who has invested heavily in “the Convergence”, a facility mostly (and notably) underground in an unspecified former Soviet republic, where cryogenic specialists are promising that the terminally ill and the super-rich will “die a while, then live forever”. Ross’s second wife is dying, and will become part of the frozen elite. She might not want to go alone. The Convergence is a place of colour-coded doors that seem to mean something and headless statues that might be the vitrified remains of their clients, with a walled garden of fibreglass flowers and artificial breezes, and ubiquitous screens replaying images of mass-violence, self-immolation and human tragedy.

Reading this novel is like having your fortune told by a Tarot reader who has designed his own enigmatic cards. The Monk who paces the corridors and says, “They come here to die. This is their operational role.” The Twins who built the Convergence, part philosophers, part Sophists, part avant garde artists. The Orphan Who Runs Away, the adopted child of Jeffrey’s intermittent lover. The Archaeologist Step-Mother, whose life has been about the past and who is committed to an unknowable future. The Mother, whose name Ross cannot utter, who says to her son in a moment of strange epiphany, “The vivid boy… the shapeless man”. A man who calls himself Ben-Ezra, with a silver skull-cap, who has been reached “magically” since Jeffrey has “managed to avoid the usual safeguards”, who details the language the dead are learning – “a system that will offer new meanings, entire new levels of perception”. What does it mean?

What it means is that the search for meaning is what makes us meaningful. The most poetic and moving section of the novel details the thoughts of Jeffrey’s stepmother inside the limbo between dying and being reborn or remade or restarted. “Am I just the words. I know that there is more. Does she need third person… But am I who I was.”

Words matter throughout this novel. Jeffrey has a habit of “naming” people – we know that the Stenmark Twins aren’t called the Stenmarks: it is just Jeffrey’s imposition of what he thinks they ought to be called. His life has been determined by his desire to be specific about words and things – “What is lint?” he once proposed. Significant moments are marked by a word, or phrase, in significant circumstances that Jeffrey is confronted to parse into something meaningful. It might be a phrase like, “I’m not someone I’m supposed to be” or “gesso on linen” – which sent me down bizarre paths that ended in Ethiopian Church Art. But it’s actually the profound idea that the world is made of words and words are inadequate to catch it all.

This is a novel where the crypt and the cryptic merge. The word that circled in my head, and I am almost ashamed to commit it to print, is how noble a novel it is. It is serious. It demands the reader be serious. It is about serious things – the old end things of religion: death, judgment, heaven and hell. It is quietly apocalyptic and snarls in its margins. Eli Horowitz and Chris Adrian have recently written a brilliant novel about how immortality might afflict us – The New World. In their book, it was death vs love. In DeLillo, it is death vs humanity. “Catastrophe is our bedtime story”, says Lockhart, with his allegorically locked heart. If this is not on the Man Booker longlist, then something is awry indeed.