Book review: Young Mungo, by Douglas Stuart

Winning the Booker Prize for your debut work is not an automatic ticket to literary Elysium. It was many years before Arundhati Roy produced another novel after The God of Small Things, and even then it partook more of her polemics than her storytelling. DBC Pierre has written several novels after Vernon God Little and most should come with a sticker saying “I can’t believe I’m getting away with this”. Aravind Adiga has done several novels, and most of them have passed the reading (or buying) public by; though I rather liked Election Day. So what do we make of Scotland’s own Douglas Stuart, with his first novel after Shuggie Bain won the Booker Prize? It is a rather problematic proposition. The First Minister Nicola Sturgeon opined that, on the basis of a pre-publication copy, she “wasn’t sure if Young Mungo could live up to Shuggie Bain, but it surpasses it”. I am not tasked with running a country, but I do know a thing or two about books.

Young Mungo is a form of self-plagiarism. One can tick off the common concerns: maternal alcoholism, sectarian violence, a burgeoning awareness of adolescent gay sexuality, poverty, rape, grooming, drugs, the poor quality of Glaswegian cuisine. It is as if the pack of cards marked “themes” has been reshuffled. Walter Scott wrote of Tobias Smollett that his second novel was “sedulously laboured into excellence”. Shuggie Bain did have a quality of seething and barely repressed, pressure-cooker pressure, and I feel Scott’s observation – exciting scrappiness versus immaculate polish – holds here. The story, if you like, too obviously has “a story” rather than an atmosphere.

Advertisement

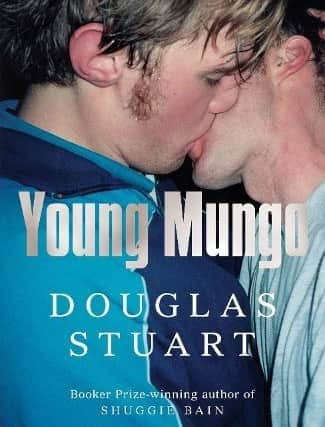

Hide AdMungo Hamilton is the youngest of three. His older sister, Jodie, is a steely, uncompromising and sometimes dislikeable young woman, left in the lurch by their mother’s frequent booze-related absences. His older brother, Hamish, is eminently dislikeable, as the capo of a gang of Protestant thugs. It will come as not surprise whatsoever that Mungo is the one confused about his sexuality. One need not read a page to know this: the front cover shows two teenage boys kissing and the dust jacket gives away half the plot. But even without the paraphernalia of how the book is marketed, a subtle reader would guess from the opening pages, where Mungo is described as someone who “smiled when he didn’t want to. He would do anything just to make other people feel better”, that he is “sensitive”. In the course of the book Mungo will meet and fall in love with James, who is a pigeon fancier, more comfortable with his sexuality and – drum roll – a Catholic.

That however comes later in the arrangement of the novel but chronologically before the beginning of it. It is a method – “in media res”, “in the middle of things” – which is traditional and highly effective. It creates a narrative hook (why is this happening now, and what had led to it, and what shall be the consequences?) The problem here, however, is that marketing and structure are undercutting each other. We open with Mungo being sent off with two strangers for a long weekend in the countryside, to learn fishing and lighting fires and snaring rabbits. The two men have “slitted eyes” and their “hands ferreted inside their trouser pockets as they pulled their ball sacks from their thighs”. They promise “a proper boy’s weekend” to “make a man of you yet”. Honest to God, by page 14 I noted that this rural jaunt is going to end in rape. I was right. Likewise, when Hamish gives Mungo a knife it conforms to the Chekhov gun principle. It is going to get used, on whom being the only question.

The prose is fluent enough, but has a tendency towards the easy image. In the first few pages we have she “knew the bag was not heavy. She knew it was the bones of him that had become a dead weight”. People are “beetroot-red” and “poached pink by the sun”, blood has a “metallic taste”, sleep is “fitful”, sunlight invariably “dappled”. None of this is particularly irksome, it just makes one wish for a sudden, freshly-minted image. Likewise, the characterisation tends to reduce to “features”. What makes Mungo unique? Despite being good-looking he has tics. His sister ends each conversation with an annoying laugh. His radge brother is actually short and wears glasses. It is like a marker in the place of psychology.

There are some things of interest here. The relationship with James is done tenderly, although the prose again becomes pedestrian, or rather “aspiring poetical”: “an eyeful of alabaster and rose, the glacial blue of inner arms with their veins like violet rivers… the fields of fevered carnations blooming high in his pale collarbone”. The idea that their mother is both herself and Tattie-bogle when drunk is a convincing fracture in a young mind.

Young Mungo is not a bad book. It is a book that suffers from seeming as if it has already been read. Winning the Booker ought to give carte-blanche to an author. To choose to do what you have already done seems like a wasted opportunity.

Young Mungo, by Douglas Stuart, Picador, £16.99

A message from the Editor:

Thank you for reading this article. We're more reliant on your support than ever as the shift in consumer habits brought about by coronavirus impacts our advertisers.

If you haven't already, please consider supporting our trusted, fact-checked journalism by taking out a digital subscription at https://www.scotsman.com/subscriptions