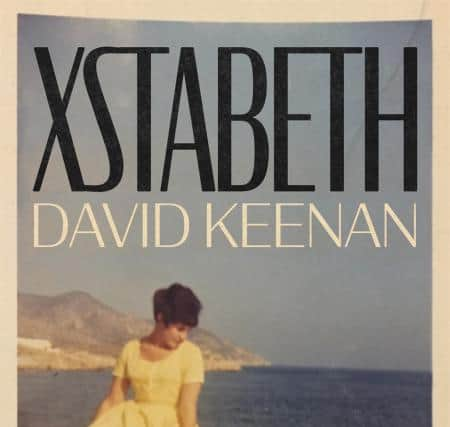

Book review: Xstabeth, by David Keenan

As a long-established (or long-anti-established?) contributor to and documenter of the obscurer corners of British musical culture, David Keenan could easily have penned one of those music critic memoirs in which rock’n’roll epiphany ends the author’s emotional isolation and secures his escape from suburban ordinariness. Instead, with his 2017 debut novel This is Memorial Device, Keenan put a subversive, speculative twist on the genre of self-analysis through musical memory. His hometown, Airdrie, was presented not as a philistine backwater for the cool and clever to kick against, but as a magically generative place, with a local music scene charged not so much by ambition to “make it” as by an otherworldly drive towards transcendence.

Keenan is the kind of writer who can look forward to being lovingly over-interpreted into perpetuity, but one relatively simple angle on his work is that it flips the order of cultural authority – it presents the art and artistic personae generated by ordinary people as sacred phenomena, which might be beyond beyond the simple reckoning of elites, although they can be encouraged to understand. This celebration of the spontaneous, the indigenous and the unauthorised continued with 2019’s For the Good Times, which was set in Keenan’s father’s native Belfast, and made a pop culture-suffused phantasmagoria of the “Troubles”.

Advertisement

Hide AdKeenan attracts numerous comparisons, to Beats, magic realists and iconoclasts from Kafka and Kundera to Burroughs and Bolaño. In terms of Scottish literature, a useful point of comparison may be the late Alasdair Gray – not because the writing styles are especially similar, but because both men present mythic, mystical and hysterical perceptions of human activity not as inspired or freakish or special, but as straightforwardly real. Where Gray’s invocation of the uncanny is frequently pained, however, an interesting climatic feature of the Keenan universe is its low incidence of angst. This despite the fact that Keenan manages to kill off by suicide a character named “David W Keenan” on this novel’s very first page…

According to this framing device, what we are reading when we read Xstabeth is a lost novel by “David W Keenan”, subsequently rediscovered and annotated by a scholars of “magick, tarot and bibliomancy.” Having killed himself, however, Keenan shifts his primary fictional voice decisively away from the autobiographical, in order to occupy the perspective of a young Russian woman named Aneliya. (Expect no apology for “cultural appropriation” here, nor indeed for the prodding of any other modish sensitivities.) The book’s title refers to an experience undergone by Aneliya’s father, a washed-up musician: an extraordinary outpouring of creativity, which he experiences as a sort of visitation. “The music was making demands of him,” Aneliya records. “…Like it was a prison warden in a gulag… Then it told him its name. It said its name was Xstabeth.”

This is such a delicious idea, you’d think it would dominate this whole short, punchy book. It’s a mark of Keenan’s engaging contrariness, however, that his high concept is but one of many matters competing for his narrator’s attention. Aneliya is also occupied with trying to look after this mercurial, vulnerable artist parent of hers; with covering up the fact that she’s having an affair with his old friend and musical rival, Jaco; and with managing the emotional legacy of her mother’s unexplained demise, about which both men may know more than they have shared. Oh, and she’s pregnant. Keenan conveys Aneliya’s tumult of thoughts in a staccato sentence style that’s off-putting at first, but soon becomes both accessible and strangely soothing – a living pulse for the narrative:

‘…He said. Can you play golf at night. Of course not. The famous golfer said. That’s ridiculous. But after what he said why. Then the famous golfer invited us to a party. There is a party at our hotel in The Scores. He told us. Why not join us later. Why not.”

The golfer, whom the pair encounter on a pilgrimage from St Petersburg to St Andrews, becomes a source of fascinating philosophical inquiry regarding time and consciousness, and of a sexual affair of incongruous squalidity for Aneliya. It’s odd, to this reader at least, that Keenan’s interest in transcendence doesn’t extend to the rejection of hackneyed sexual groupthink. Everyone has their turn-ons, of course, some of which are potent precisely because they lack refinement; but it still might have been cool for this young woman to get sexually awakened without recourse to strip clubs, suspenders, punitive and painful sex acts and getting called a little bitch. Still, Keenan’s marriage of the sordid to the sublime and the erudite to the bluntly instinctual is a phenomenon to be treasured. Though possessed of a driving intensity and an abundance of ideas, his prose never feels didactic or dry. It’s an invitation to share in what he feels – as raw, warm, bloody and poignant as it is intellectually engaged.

Xstabeth, by David Kennan, White Rabbit, 14.99

A message from the Editor

Thank you for reading this story on our website. While I have your attention, I also have an important request to make of you.

Advertisement

Hide AdThe dramatic events of 2020 are having a major impact on many of our advertisers - and consequently the revenue we receive. We are now more reliant than ever on you taking out a digital subscription to support our journalism.

To subscribe to scotsman.com and enjoy unlimited access to Scottish news and information online and on our app, visit https://www.scotsman.com/subscriptions

Joy Yates, Editorial Director